The Second Hundred Years’ War

15 August 2015

Saturday

In a series of posts I started last summer, A Century of Industrialized Warfare, I reflected on some of the significant 100 year anniversaries of the First World War. There are many more centennials yet to come. There is, in fact, almost a century of centennials from a century of almost continuous warfare.

Many have made the claim that the First and Second World Wars were one war with a twenty year hiatus (to rearm and regroup) ever since Marshal Ferdinand Foch, upon seeing the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, summarily announced, “This is not a peace. It is an armistice for twenty years.” (Foch was not one of those, like Keynes, who saw the terms as too harsh; Foch was disturbed that Germany was not completely dismembered as nation-state.) This reasoning can be extrapolated beyond the First and Second World Wars, which was followed immediately by the Cold War, and so on. If we make this extrapolation, we have a period of armed conflict rivaled in its duration only by the Hundred Years’ War.

The Hundred Years’ War was a construction of later historians: no one in the fourteenth and fifteenth century called the series of conflicts between the English and the French the “Hundred Years’ War,” and no one today calls the series of conflicts triggered by the First World War the “Second Hundred Years’ War,” though we can use the second term with as much justification as the first. Our periodizations are devices that we employ to attempt to help us better understand the past. While our metaphysical ambition is to carve nature at the joints, it is not clear that we can do this with history, i.e., that there is an intrinsic metaphysical structure to history. And we might understand the past century better if we understood out time as the Second Hundred Years’ War.

As the Hundred Years’ War is divided into a periodization of the Edwardian Era War (1337–1360), the Caroline War (1369–1389), and the Lancastrian War (1415–1453), so too we can divide the Second Hundred Years’ War into World War One, World War Two, The Cold War… and then whatever historians will eventually call our present stage of instability consisting of a series of Balkan wars, Persian Gulf wars, Central Asian wars, and the “War on Terror.” In both cases — that is to say, in both Hundred Year wars — the outcome of each major conflict created the conditions for the conflict to follow, and follow they did, with a dreary inevitability.

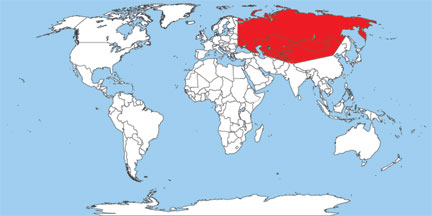

If the First Hundred Years’ War was about who would control the largest kingdom on the European continent (i.e., France), the Second Hundred Years’ War is about a political settlement in the context of industrial-technological civilization, when civilization is global. In other words, the Second Hundred Years’ War is about who will control the planet. This was already implicit in the geopolitics that led up to the First and Second World Wars, specifically, in Mackinder’s doctrine (sometimes called The Geographical Pivot of History) that, “Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island commands the world.” (Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality, p. 150)

Interestingly, the geographical area that Mackinder identified as the Heartland closely corresponds to the geographical region that David Christian calls Inner Eurasia.

I am not defending Mackinder’s view, which is still today discussed by geostrategists; I have observed elsewhere that Mackinder’s focus on land power was balanced by Alfred Thayer Mahan’s focus on sea power. The world-island, after all, is situated in the world-sea, and either can be a pathway to global dominion. But, really, this is not very interesting any more. No one talks about world dominion in explicit terms these days (except for villains in James Bond films), while the practical and pragmatic approaches to global power projection no longer look like Mackinder (or Mahan).

Inner Eurasia: The huge interior landmass of Eurasia, whose dominant features are flat, semi-arid regions of steppe and forest, is known as Inner Eurasia. David Christian defines Inner Eurasia as the territories ruled by the Soviet Union before its collapse, together with Mongolia and parts of western China. Poland and Hungary on the west and Manchuria (northeastern China) on the east may be thought of as Inner Eurasia’s borderlands. The northern margins are boreal forest and Arctic tundra. The southern boundaries are the Himalayas and other mountain chains.

Nevertheless, there is a sense in which the global political system, which cannot avoid being global today because of the way all civilizations are crowded up against each other, seeks an equilibrium, and an equilibrium would be some global settlement of power relationships that would allow for an internal security regime in each nation-state and an external security regime that minimized conflict and facilitated trade and commerce. If this is what “global dominion” means today, so be it. Perhaps you would prefer to call it peace. Whatever you call it, this is what it will take to end the Second Hundred Years’ War.

. . . . .

. . . . .

A Century of Industrialized Warfare

0. A Century of Industrialized Warfare

4. A Blank Check for Austria-Hungary

5. Serbia and Austria-Hungary Mobilize

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .