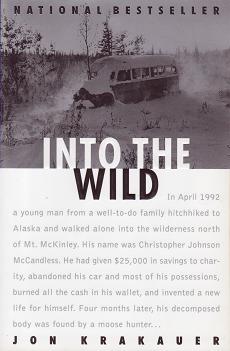

Krakauer on McCandless

7 October 2009

Wednesday

Christopher Johnson McCandless, AKA Alexander Supertramp

I usually don’t bother with bestsellers (even when they’re more than ten years old), but I’m now listening to Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild, about the short and strange life of Christopher J. McCandless, whose claim to fame was being found dead in Alaska after tramping around the American West for a few years. The second most prominent character in Into the Wild is the author of the book, John Krakauer himself. I don’t count this a bad thing that the author injects himself into the narrative. On the contrary, I think it makes for an honest account to come clean about one’s interest in one’s subject matter. Krakauer wrote a passionate book because he obviously felt an immediate affinity for Chris McCandless. It is sympathy based on shared experience that makes it possible for a biographer to employ what Collingwood called the a priori imagination to enter into the life of his subject.

Just before Into the Wild I listened to Dave Cullen’s well-reviewed Columbine, about the Columbine school massacre of 20 April 1999, which revealed all-too-clearly the author’s inability to inhabit the skin of his subjects. The a priori imagination has its limits: it is facilitated by sympathy and shared experience; it is frustrated by differences in temperament and inclination. Dave Cullen’s book is passionate in its own way, but you can feel Cullen’s struggle to try to get into the heads of the killers, and the careful reader will spot the points where, despite his efforts, he manifestly fails to do so.

I can easily imagine someone being indignant and scandalized that I mention Chris McCandless and the Columbine killers in the same context, but it’s not really that much of a stretch. It is obvious from the portraits of them that all were angry young men. Sure, McCandless is smiling in in last photograph when he knows that he is going to die, and Krakauer writes that, “He is smiling in the picture, and there is no mistaking the look in his eyes: Chris McCandless was at peace, serene as a monk gone to God.” He found peace, but he had to punish his family with his absence and silence in order to find that peace. This is somewhat less vindictive than mass murder, and certainly morally preferable, but it is a difference in degree, and not a difference in kind. The idealistic temperament is intrinsically punitive.

The last photographic self portrait of Chris McCandless, holding his farewell note and waving to the camera.

All these angry young men were precociously intelligent, and really didn’t know how to make a place for themselves within the bureaucratized and institutionalized world of technological civilization. McCandless wasn’t just another vagabond, he was a vagabond as a matter of principle. Among the pleasures of Krakauer’s book are the many quotes from books that Chris McCandless had taken with him to Alaska in his backpack, passages underlined by McCandless in Tolstoy and Emerson and others. People took McCandless for a tramp at first sight, but it is obvious from the book that when he opened up it must have been a shock to discover that he was educated and articulate and had chosen his unconventional life as a matter of intellectual conviction, which is a rare thing.

Jon Krakauer wrote a compelling book about Chris McCandless because of his personal interest in the story, which grew out of his personal experiences.

But erudition, intelligence, and an ability to articulate one’s insights into life, admirable though they are, are not enough. One can be well read in the classics, and have great insight into the way the world works, and still get things wrong. Angry young men often mellow with age, but when they die as angry young men and leave only the actions and the opinions of angry young men, they never give themselves the chance to mellow, and they stand as symbols to angry young men ever after. The written word never mellows: Litera scripta manet (as it says on the Reed College library book plate).

Burning one's money is a dramatic gesture, and precisely for this reason it is not an entirely honest gesture. Life here imitates performance art, and the line between the two becomes blurred.

In many of the incidents described by Krakauer, as well as the journals and photographs left by McCandless, there is something theatrical, something smacking of superfluous and self-conscious symbolism, like making a fire with one’s remaining currency. McCandless, like Wittgenstein, gave away his money and intentionally impoverished himself. It is a perennial impulse that often converges on a perennial gesture. The idea of it is noble, but few have the nobility to pull it off with grace and honor. This is insufficiently appreciated: one can glimpse a noble ideal, and make a gesture in that direction, perhaps even a profound gesture. But life is more than gestures. After the gesture, one must go on living or make of the gesture also a farewell to life.

There was a pervasive idea in the pre-modern period that truth is to be found at the fons et origo of the world. The world as it is, the world as we find it, was thought to be corrupt, decadent, and nearing its end. Truth was not to be found in such a world. Truth was to be found by going back into the past, and especially back to the primordial origins of the world. It was believed the the Golden Age of man was long past, and as the clock of history ran down matters only became worse, and the further distant we grew from our origins, the further we grew apart from truth.

One of the more absurd consequences of this idea was the fetish for “ancient wisdom.” Our medieval forebears did not believe that knowledge increased as civilization progressed, because they did not believe that civilization progressed. Civilization, for the medieval mind, was in permanent and terminal decline until the end of days. To find wisdom, knowledge, and truth, then, one did not look to the latest book, but to the oldest book. To feed this desire for ancient wisdom, ancient wisdom was created from whole cloth. Books were written and credited to the authorship of ancient sages like Pythagoras or Hermes Trismegistus. Puerile and mediocre nuggets of “wisdom” were passed off to credulous seekers who thought that what they were reading was profound because it was old, though it was in fact neither.

All of these ideas are familiar sentiments today — too familiar, frighteningly familiar. Despite our modernity, there are regions of the mind that are still thoroughly medieval. The modern version of the idea that truth is to be found in the distant past, dimmed from our sight, inaccessible, and therefore all too easily romanticized, is the idea that truth, wisdom, and knowledge are to be found in a primordial experience. The primordial experience as we imagine it today is the experience of nature, and especially nature in the form of the untrammeled wilderness. Many seekers of the modern world, from the “back to the land” movement of the 1960s counter-culture to contemporaries who see themselves following in the footsteps of John Muir and Henry David Thoreau, imagine that only by abandoning civilization and going into the wild can one be truly alive and come face to face with the truth of the human condition. I do not doubt that some people do, in fact, find the truth they are seeking through an encounter with the primordial, however the primordial is conceived, but as a general proposition the ideal of primordial truth is illusory more often than not.

. . . . .

. . . . .

Thanks for the info on Chris and your input.

[…] to the picture from (https://geopolicraticus.wordpress.com/2009/10/07/krakauer-on-mccandless/) taken from an English blog, Jon Krakauer has short silver tousled hair and hidden cheekbones; his […]