Addendum on Classifying the Second World War

20 June 2020

Saturday

In What kind of war was the Second World War? I made this observation:

Knowledge inevitably involves imposing a template on the messiness of actuality in order to organize our experience rationally and coherently, so that the more systematic our organization of experience, the more knowledge we could be said to possess of this experience. Taxonomies of war seek to systematically organize our experience of war into knowledge of war, and from knowledge of war comes efficacy in waging war.

How exactly does this play out? Isn’t this a rather abstract claim to make about the messy reality of war? How does classification contribute to knowledge of war, and how does knowledge of war contribute to efficacy in waging war?

I can think of a couple of ways to argue this point, one a rather long digression through epistemology, and the other a rather shorter route through more familiar territory. I think I’ll save my epistemic exposition for another time, and at present only discuss the obvious way of cashing out this apparently abstract claim.

In brief, if we classify a war (or an operation, or a battle, or a skirmish) incorrectly, then we have located this event in a particular epistemic space, with relations to other related events and actions, and these other events and actions might bear some kind of relationship to the event in question, but these relations all will be a little off, misleading, and perhaps fatally misleading. If, on the other hand, we get the classification of the event correct, then our knowledge of that event will be reliable and not misleading. We will be able to act with confidence that are actions are based in the reality of the situation.

If you believe yourself to be fighting a war of national liberation, but you are actually allowing your nation-state to be used as a proxy war in great power competition, then you are going to be fighting the wrong war as long as you hold this erroneous belief, and the likelihood of your ultimately realizing your war aim of national liberation is rather poor. Contrariwise, if you believe yourself to be without agency, a mere pawn of external forces, whereas you are really engaged in a struggle of national liberation, or if you have a histrionic belief in being a great power engaged in a great power competition whereas in fact you are engaged in a petty struggle for the limited spoils of a banana republic, again, you will be fighting the wrong war, and you are not likely to successfully secure your war aims.

Self-deception plays a large role in this. Self-deception as it relates to warfare is relevant when political and military leaders deceive themselves, or when the masses are caught up in some madness of crowds (like the August Madness). While there is little that can be done about the madness of crowds, other than to wait for it so exhaust itself, the madness of political and military leaders is other matter. Deluded leaders can do far more harm than deluded masses, but it is also easier either to replace a deluded politician or general, or for this deluded individual to find their way back to reality.

The problem of deluded military and political leaders was presumably the motive for this advice from Sun Tzu:

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.”

This is the Socratic imperative to know thyself, displaced into war. It is equally necessary to disillusion oneself, and to inspire delusion in the enemy, which brings us to another Sun Tzu quote that speaks to the disconnect between reality and war aims that characterizes deception:

“All warfare is based on deception. Hence, when we are able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must appear inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near.”

All warfare is based on deception, yes, but there are two aspects of deception: not being deceived oneself, and deceiving the enemy. In the western tradition, these two ideas are incorporated into most lists of the principles of war in the form of surprise and security. Surprise is when you have successfully deceived the enemy and you are able to take the offensive to achieve your objective with the enemy on his back foot, as it were. Security is the need to take precautions so that when you have been surprised (i.e., deceived) the result is not disastrous and you can recover your position, or limit the damage in defeat. Surprise is what you get when your enemy incorrectly classifies the war (operation, battle) they are fighting, and security is what you need when you have misclassified the conflict you are in.

The history of war is filled with telling examples of delusion and deception. For an example of delusion, after the experience of trench warfare during the First World War, France responded to the threat of another German incursion by building the Maginot Line, which has subsequently become a synonym for inefficacy. But the French had simply observed the nature of the bulk of the First World War, and projected another war in the future that would also be a stagnant conflict in which defense had the advantage over offense. While the French were building the Maginot Line, the Germans were pressing forward with both the theory and practice of mobile armor. To skirt the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, the Germans actually made a deal to train tank crews in Russia, where Heinz Guderian spent some time on maneuvers.

The French spent about three billion Francs on the Maginot Line. This could have purchased about 5,000 Renault R35 tanks in 1936 currency. The French could have quadrupled their tank force, with money left over to buy copies of Guderian’s Achtung — Panzer! as well as training for French tank crews. This would have served France better than spending the money on the Maginot Line, but the French were not expecting a war of rapid maneuver in which an armored spearhead penetrating a defensive line at its weakest spot would be the key to victory.

For an example of deception, prior to the Normandy landing the Allies conducted an extensive campaign of deception that involved dummy tanks and airplanes to fool German observers.The Germans knew that an assault was coming, but they did not know where exactly. We know from records obtained after the fact that in the lead up to the Allied landing that the Germans re-deployed some of their forces away from the actual landing zone to an area suggested by the deception, so that the deception was at least partially successful.

Before this, in the lead up the invasion of Sicily, one of the more elaborate deceptions of the Second World War, Operation Mincemeat, involved dropping a body with a fabricated backstory and diplomatic documents off the coast of Huelva, Spain, so that the body would wash up on the beach. It is not known if this deception ultimately contributed to the Allied victory in Sicily, but the elaborate ruse did come off as planned. For anyone who wants an introduction to espionage at its best, it is worthwhile to study the British secret services during the Second World War, as their achievements were remarkable (e.g., every German spy in England was turned by the end of the war), and Operation Mincemeat was truly inspirational, whether or not it contributed to Allied victory.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

What kind of war was the Second World War?

11 June 2020

Thursday

Azerbaijani legionnaire from the 804th Azerbaijani infantry battalion

The Second World War will be studied by historians as long as human civilization endures, since the scope and scale of the conflict puts it in a class by itself, but what kind of war was it? What kind of war was the Second World War? It is a deceptively simple question, since it implies that there is some kind of taxonomy of warfare, and that the Second World War neatly fits into some taxon. Thus the question implicitly appeals to theories of war that remain unstated in the question. One could relativize the inquiry with some formulation like, “According to a Marxist perspective, what kind of war was the Second World War?” This would at least make our theoretical framework explicit, and would narrow the inquiry to a manageable scope. I’m going to tackle the subject in an open-ended way, without doing this.

A North African soldier from the Free Arabian Legion and a Cossack volunteer.

Some years ago I formulated a taxonomy of war (largely building on the ideas of Anatol Rapoport) that schematically distinguished between political war (human agency), eschatological war (non-human agency), catastrophic war (human non-agency), and naturalistic war (non-human non-agency) — I didn’t systematically develop this schema in relation to war to the point of writing a post on each kind of war, but cf. More on Clausewitz, Three Conceptions of History, The Naturalistic Conception of History, Revolution and Human Agency, and Cosmic War: An Eschatological Conception (every conception of history implies a conception of war, and vice versa; moreover, every conception of war implies a conception of civilization, and vice versa). While this schematism possesses an enviable neatness (when systematically laid out), in retrospect it appears to me as being a bit too neat, and therefore not always helpfully reflective of the messiness of the actual world. And war is perhaps the messiest manifestation of the actual world.

Soldiers of the Free Indian Legion of the German Army, with a Luftwaffe Member, 1944.

If we abandon the attempt to explicitly formulate a taxonomy, we can distinguish wars of conquest, imperialist wars, resource wars, geostrategic wars, ideological wars, genocidal wars or wars of extermination, and so on. This grab bag of classifications is not unlike our classifications of science — empirical science, natural science, physical science, social science, historical science, and so on — in so far as there is no overarching conception that systematically relates the parts to each other and to the whole. For a messy world, there is a certain inevitability to messy systems of classification, but our taxonomies of classification should be no more messy than is absolutely necessary. Knowledge inevitably involves imposing a template on the messiness of actuality in order to organize our experience rationally and coherently, so that the more systematic our organization of experience, the more knowledge we could be said to possess of this experience. Taxonomies of war seek to systematically organize our experience of war into knowledge of war, and from knowledge of war comes efficacy in waging war.

The Clausewitzean approach is to define war and then to refine and elaborate the definition in order to illuminate the nature of war, rather than to converge upon a taxonomy of kinds of war. In Book Two, Chapter One of On War, Clausewitz does discuss the classification of war, and Clausewitz did note some kinds of war, for example, his distinction between absolute and real war. In Book Eight of On War Clausewitz comes to focus on the outcomes of war as persistently as he focused on the definition of war in Book One, and in focusing on outcomes Clausewitz distinguished between real war and absolute war, which latter is often assimilated to Erich Ludendorff’s conception of “totale Krieg”. (An interesting discussion of this can be found in “The Idea of Total War: From Clausewitz to Ludendorff” by Jan Willem Honig; also cf. “Controversy: Total War” by Daniel Marc Segesser.)

Bundesarchiv Bild 101I-295-1560-22, Nordfrankreich, Turkmenische Freiwillige, photograph by Karl Müller

Real war, for Clausewitz (and in contradistinction to absolute war), is what we today would call limited war, but absolute war is the paradigm of war and the criterion against which any other conception must be measured, here expressed in the context of Clausewitz’s political conception of war: “If war belongs to policy, it will naturally take its character from thence. If policy is grand and powerful, so will also be the war, and this may be carried to the point at which war attains to its absolute form.” (Book Eight, Chapter 6, B) However, no great emphasis is given to the classification of war in Clausewitz. This has left taxonomies of war underdeveloped in the post-Clausewitzean literature. If Carnap was correct that scientific concepts develop from taxonomic (classificatory), through comparative, to quantitative concepts (though we are under no obligation to accept this schema of scientific development, but at least it offers a framework), then the underdevelopment of taxonomic concepts for warfare represents a failure in the development of a truly scientific understanding of war.

We can adopt the Clausewitzean approach and begin with a definition of war, which then defines the class of all wars, and then we can decompose the class of all wars into subclasses that define kinds of war. Any good taxonomy (by which I mean any taxonomy useful and fruitful for research) will involve a schematization of a complex and ambiguous reality that results in simplification. One of the most difficult aspects of scientific abstraction is finding the “just right” point between too much fidelity to empirical fact, which makes schematization impossible, and over-simplification, which falsifies empirical reality to an unhelpful extent. Ideally we would want a principled classification that decomposes all wars into a finite number of classes, each of which is mutually exclusive of the others, and each of which exemplifies an unambiguous idea. The ideal of classification is rarely realized, so we are often thrown back on a classification based on contingent properties. There are several contingent properties that characterize the Second World War and so furnish us with the most familiar, even if not rigorous, classifications. These contingent properties do not result in mutually-exclusive, non-overlapping classes, which means that there is overlap among kinds of wars. The Second World War was an industrialized war, but the Russo-Japanese War and the First World War were also industrialized wars. It was a planetary-scale war, but The Seven Years’ War and the First World War were also both planetary-scale wars. From the Second World War being a planetary-scale war it follows that it was a war fought on multiple fronts and in multiple theaters among a wide variety of combatants drawn from many nation-states. The Second World War was more a war of maneuver than attrition, more about offense and initiative than defense and stagnation. In this it differs significantly from the First World War, but resembles the Napoleonic Wars.

Beyond a haphazard classification of war by overlapping contingent properties, there are reflective taxonomies that seek to organize our knowledge of war around principles of war, but which embody no overarching conception that unifies the principles employed. This is the status of Anatol Rapoport’s distinction among political, eschatological, and cataclysmic philosophies of war, mentioned above (but which I developed in accordance with an overarching conception of agency). Another example can be found in Ian Clark’s Waging War: A Philosophical Introduction (pp. 19-23), which distinguishes six concepts of war, as follows (the headings below are Clark’s, but the explanations and commentaries that follow each heading are mine), and which I will examine in relation to planetary-scale warfare:

● War as instinctive violence — This could be called the evolutionary or biological conception of war. As Freud once wrote, “…men are not gentle creatures who want to be loved, and who at the most can defend themselves if they are attack; they are, on the contrary, creatures among whose instinctual endowments is to be reckoned a powerful share of aggressiveness.” This was written long before evolutionary psychology had been formulated, but further work in evolution, biology, and psychology has underlined Freud’s assertion with voluminous evidence, including something like war fought among chimpanzees in the wild. If human beings are instinctively violent, then it should not be surprising that human beings organized by civilization should engage in organized violence on a scale proportional to their organization, and this is what was exhibited in the global industrialized wars of the twentieth century.

● War as divination or legal trial — We could also call this “war as a decision procedure.” In so far as the decision procedure of war invokes divine sanction on its side, it also becomes an eschatological war, but it is at least arguable that its eschatological character is epiphenomenal in the context of war as a decision procedure. The point is to settle a dispute, and in so far as war has a decisive outcome (which is not always the case), the dispute is settled and the procedure of war has yielded a decision. In the case of a planetary-scale war of multiple theaters, there are multiple decisions simultaneously in pursuit of decision, and it cannot be expected that all of these outcomes will be decisive. This implies that planetary-scale war rarely if ever achieves an outcome that largely decides outstanding issues, hence the Second World War was followed by the Cold War.

● War as disease — This closely corresponds to what Anatol Rapoport called the cataclysmic philosophy of war, but Clark makes a distinction between war as disease and war as cataclysm: a disease can be cured, whereas a cataclysm usually cannot be prevented, so that mitigation efforts focus instead on limiting the damage and cleaning up after the fact. War as disease suggests a cure, and is therefore an abolitionist conception, but it also suggests the possibility of pandemic. If human beings, or human societies, are infected with the disease of war, then war will be spread like a disease, and at times that disease will take on the properties of a pandemic. War understood as a pandemic is planetary-scale war of planetary-scale civilization.

● War and social change — Clark glosses war as social change as war being either a measure or a means of social change. Although Clark mentions Comte and Schumpeter (focusing on economic development), this is essentially a Hegelian conception (or, if you prefer, a Marxist conception), since it is conflict that pushes the social dialectic forward; we cannot make social change without fulfilling all of the steps of the dialectic. If we look how far we have come, driven by conflict, it appears as a metric of that development; if look forward to social change yet to come, conflict appears as the means by which such change can be brought about. If we look forward to a planetary civilization, then only a planetary-scale dialectic, which involves planetary-scale war, can secure that end. This was once made very clear in some varieties of Marxism, which insisted that the peace of the communist millennium could come only after the world entire had experienced proletarian revolution and the planet entire has been unified on communist economic principles.

● War as a political instrument of the state — This conception perfectly embodies the political philosophy of war, which we usually identify with the work of Clausewitz. For the political conception of war to culminate in a planetary-scale war, the political framework must be planetary, and this planetary-scale political framework has been taking shape since the Age of Discovery, with the industrial revolution providing the technological means for effectively acting on a planetary scale at human time scales. It could be argued that it was only the twentieth century that this framework and its means came to maturity, and as soon as this maturity was achieved, planetary-scale wars were waged. This argument, however, minimizes the role of human agency (it makes war look as inevitable as a violent instinct), which agency is one of the key features of the conception of war as a political instrument. In other words, there is an interesting overlap between the most agency-centered conception of war and the least agent-centered conceptions of war.

● War as regulator of the international system — This might also be called war as the invisible hand, as the parties waging war are, by waging war, performing a function that restores the balance of power, though through no intention or plan of the parties to the conflict (Clark does not make this connection). If war is waged as the action of the invisible hand of the international system to maintain its own viability and stability, then we would also expect instances of “market failure” in which the invisible hand ceased to function. In cases of political failure (say, the failure of conception of war as a political instrument, above), the wars waged in the wake of political failure would fail to restore balance of power and confer viability and stability on the international system, cascading into planetary-scale war now free of the mechanisms that had once governed its scale and conduct (being much like the concept of war as a disease).

In the above taxonomy, there is no obvious place for what Rapoport called the eschatological philosophy of war, except as briefly mentioned under war as divination, where the eschatological aspect is epiphenomenal. We could place eschatological war under instinct or divination or elsewhere; the point isn’t to find a place for it, but to point out how haphazard taxonomies usually miss something important and fail to fully clarify that which they exhibit as central. Still, some attempt to give order to our experience is better than no attempt at all. Sometimes the only way to proceed is to work with a haphazard framework, revising and refining it with further experience and evidence, until either it converges on an effective taxonomy, or the additional experience and evidence forces a model crisis and a paradigm shift, with a new taxonomy emerging from the paradigm shift.

As the largest war of human history in scope and scale, the Second World War was also the messiest war, and therefore the most difficult to classify, but in hindsight (because of its salience in our consciousness of war) it has become a war understood in schematic terms in which the messiness is progressively erased from historical memory. Even the Cold War, in all its complexity, was simpler than the Second World War, because of the planetary-scale division between the US and the USSR was, at its basis, an us-against-them conflict, and could be reduced to this schematic dyad. The Second World War cannot be reduced to a dyad; it was a war with many fronts, many theaters, many belligerents, and many motivations for participation. When Nazi Germany set its war machine in motion and it was evident to all that this was a formidable force, there was probably a strong sense of inevitability about ultimate German victory in the war. When Poland and France had fallen and the British had retreated at Dunkirk without any means of striking the Germans except for their long-ranger bombers, and with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact keeping the Soviet Union out of the war, “Fortress Europe” looked secure, and the burden fell upon those on the outside Fortress Europe to penetrate its defenses. When the Allies did begin to penetrate the defenses of Fortress Europe, and the Soviet Union entered the war after Operation Barbarossa, the Germans had to seek more manpower for their armies.

Bosnian soldiers of the 13th Waffen Mountain Division of the SS “Handschar”

It was a relatively straight-forward matter to recruit from Soviet and Soviet bloc POWs, as many of them were passionately anti-Bolshevik and had no love for the Soviet Union. Promised the opportunity to fight for the freedom their native homelands from Soviet tyranny, many joined. These volunteers were opportunistic, not ideological. The volunteers from western European nation-states, by contrast, were more ideologically driven, though not always in the way one might guess. There were two Waffen-SS divisions of Scandinavian volunteers, the 5th Wiking and the 11th Nordland, and the different circumstances of the Scandinavian nation-states, which were very different indeed, influenced the character of the volunteers for Germany. The Finns fought the Russians in the Winter War of 1939, and thousands of Swedes volunteered to fight in Finland against the Russians, so when Hitler violated the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and went to war with the Russians, Finland became an ally of Germany (until the Moscow Armistice of 19 September 1944), one of the Axis powers, and Finland then became a “pipeline” for fighters to join the Axis cause. Sweden remained resolutely neutral throughout the war, but Norway was occupied up until the very end, and occupied Norway was governed by Vidkun Quisling, whose name has become synonymous with treachery. Quisling was an interesting figure, as he was not an opportunistic fascist nor even an anti-Semitic fascist; Quisling belonged more to ideological fascism, and even to the mystical and esoteric side of Nazism; one suspects he would have been much more comfortable with Heidegger than with Hitler or Himmler.

Soldiers of the Turkestan Legion.

The German use of foreign legions was no doubt utterly cynical, which is to say, it was pragmatic; it was equally cynical (i.e., equally opportunistic) on the part of those who sought to hitch their wagon to a star by jumping on the bandwagon of what seemed to be the most powerful military force on the planet. The Origins of the Second World War by A. J. P. Taylor, argued that Hitler himself was an opportunist, not driven by fanaticism or an insane lust for destruction, but was responding to geopolitical imperatives to which any German politician would have had to answer. Taylor’s book was controversial in the extreme (the response to it was not unlike the intensity of the response to Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem), and only time will tell its eventual reputation. Taylor’s arguments aside, we should question the idea that any war — and most especially a war as large and as complex as the Second World World — must be pigeon-holed as one and only one kind of conflict. There is the possibility that a war might be one kind of war for one of the combatants, and another kind of war entirely for another of the combatants. This is most obviously the case when a war of extermination on the part of one party to a conflict is a war of survival for the other party; those fighting only to survive need not exterminate their rivals, though they may well come to desire this end. However, it also can be the case that, when an ideological war is being fought by two or more parties of the conflict, other parties join the conflict for opportunistic reasons. This was manifestly the case during the Cold War, when the US and the USSR were locked in an ideological struggle, but third world proxy wars which the great powers attempted to contain within ideological bounds inevitably became mired both in local struggles as well as opportunistic conflicts.

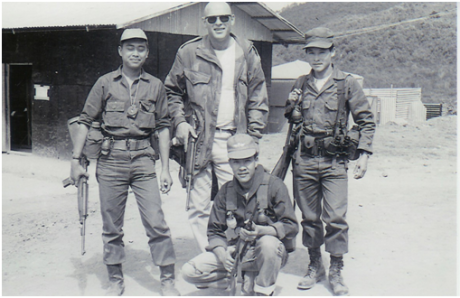

Chiang Wei-kuo, adopted son of Chiang Kai-shek, attended a German military academy and commanded a Panzer unit during the Austrian Anschluss in 1938.

Because of the diversity and multiplicity of war, there is no unity and clarity of purpose at the largest scales. For a fire team of soldiers caught in a skirmish, there is perfect unity and clarity of purpose, but this purpose doesn’t scale beyond a certain limit. The grand strategies of nation-states, kingdoms, and other political agents, constitute clarity of purpose in so far as the grand strategies themselves are clear, and impose a measure of clarity on those wars that have their origins in grand strategy, but, once a war has started, the grand strategy of any one of the parties to the conflict cannot contain the conflict within the grand strategy parameters of the originating party. The grand strategy can continue to guide developments in a war as it progresses, and so can confer a rough directionality on the conflict, but even this directionality can evaporate if the political agent attempting to pursue its grand strategy begins to lose the conflict. Precisely this occurred in the Second World War. The ideological aims of the Nazi party were rendered ambiguous by the growing scale of the conflict, and eventually become meaningless. Whether the ideological aims of political parties were ever causes of events, or whether they were, rather, responses to events — symptoms of a disease, as it were — may be a chicken-and-egg problem.

Original caption: “Treu der Kosaken-Tradition Oberfeldwebel Nicolas Balanowski, kämpft wie viele seiner Landsleute, in den Reihen der landeseigenen Verbände gegen seine früheren Unterdrücker, den Bolschewisten. Getreu der alten Kosakentradition, trägt er noch immer die Kosaken-Mütze.” In English: “True to the Cossack tradition, Sergeant Nicolas Balanowski, like many of his compatriots, fights in the ranks of the state’s associations against his former oppressors, the Bolsheviks. True to the old Cossack tradition, he still wears the Cossack hat.”

The Second World War was many wars — Theodore Ropp wrote that, “The Second World War consisted of four related major wars, each presenting separate military-political problems.” (War in the Modern World, New York: Collier, 1971, p. 314) — and these many wars of the Second World war each had a distinctive character, hence even more diversity and multiplicity than are typically to be found in smaller conflicts. On the western front, it was a straight-forward political war of the kind that had repeatedly erupted between Germany and France; on the eastern front it was a war of extermination, not unlike the German campaign in German Southwest Africa or the British campaign against the Boers during the Boer War. On the northern front, it was a static war of occupation in Norway, while on the North African front it was a mobile war of mechanized armor against mechanized armor, and in the Pacific Theater further complexities were added by the multiplicity of colonial powers and their subject peoples who were involved.

One useful distinction that can be made among kinds of war is that between methods of war on the one hand, and, on the other hand, kinds of war based on causes and objectives (which, for purposes of brevity, I will call causal taxonomies). In my post Hybrid Warfare I included a list of seventeen distinct forms of warfare recognized by the US DOD and NATO — Antisubmarine Warfare, Biological Warfare, Chemical Warfare, Directed-Energy Warfare, Electronic Warfare, Guerrilla Warfare, Irregular Warfare, Mine Warfare (also called Land Mine Warfare), Multinational Warfare, Naval Coastal Warfare, Naval Expeditionary Warfare, Naval Special Warfare, Nuclear Warfare (also called Atomic Warfare), Surface Warfare, Unconventional Warfare, and Under Sea Warfare — all of which are methods of warfare, constituting a methodological taxonomy. Needless to say, the US DOD and NATO do not recognize wars of extermination as a distinct mode of warfare, but it could be conceived as such. More importantly, these methods of war tell us very little about causal taxonomies of war, even when methods and outcomes are mutually implicated (as in genocidal wars of extermination). The taxonomy of war employed by Ian Clark, discussed above, clearly draws a connection between methodological taxonomies and causal taxonomies, as each kind of war suggests methods of waging war, or methods of mitigating war, but for Clark, as I read him, it is the causal taxonomies that are fundamental, and the methods of waging war follow from these causal imperatives. Methodological taxonomies may satisfy war planners and unify soldiers and command structures, but they do not touch on the motivations of the mass societies of planetary civilization to wage war.

Planetary-scale war like the Second World War was not possible until there was planetary-scale civilization. The planetary-scale war that was the Second World War was both enabled by planetary-scale civilization and ultimately extended planetary-scale civilization (suggesting Clark’s war as social change), as became clear in the post-war period when there was a new impetus to create planetary institutions — the UN, the EU, and eventually the WTO and the World Criminal Court, inter alia. As I have argued on many occasions, our planetary-scale civilization is not politically or legally unified, although it is culturally, technologically, economically, and scientifically unified. Within a planetary-scale civilization, Huntington’s “clash of civilization” thesis is meaningless, and therefore stillborn. On a planet well on the way to integrating planetary-scale civilization there could be wars that break out between and among partially assimilated remnants of civilizations (formerly isolated regional civilization), which would constitute the trailing edge of Huntington’s clash of civilizations, and which latter could be said to have peaked in the 16th or 17th century. In this planetary context one can certainly imagine conflicts over control of Makinder’s world-island (“Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland. Who rules the Heartland commands the World Island. Who rules the World Island commands the World.”), which would be essentially planetary-scale wars with planetary-scale methods and objectives, but which were not wars breaking out along the fault lines of civilizations.

Another way to think about wars in terms of outcomes (causal taxonomies) is that at least part of what makes a war the kind of war that it is, is the kind of peace that is possible following upon the end of the war (the actual outcome in contradistinction to the envisioned outcome, i.e., the war aim). While a war may begin with clear war aims, the war itself may cloud these war aims or make their achievement impossible, so that the actual outcome of the war is no longer recognizably related to the war aims of any of the parties to the conflict at the initiation of hostilities. In the case of the Second World War, the peace that followed was itself a war: the Cold War. Planetary-scale peace at the end of planetary-scale war came at the cost of small-scale regional wars and an arms race on a planetary scale. The decisive defeat of the Axis Powers was an unambiguously achieved war aim, but it was achieved by allies that were as ideologically opposed to each other as they were opposed to the Axis Powers. This set the stage for the conflicts to follow. Peace and reconstruction was geographically regional (not on a planetary scale, like the war itself) and was ideologically driven to a much greater extent than the pragmatic conduct of the war itself. Before the war was over Ernst Jünger had written, “It may safely be said that this war has been humanity’s first joint effort. The peace that ends it must be the second.” (The Peace, Hinsdale: Henry Regnery, 1948, p. 19) This was not to be the case, though FDR and the US tried to realize this ideal.

Ernst Jünger and Carl Schmitt in Paris.

A familiar narrative (especially to Americans) is that the Second World War was “The Good War” that was fought by the “greatest generation” (i.e., it was a just war, to invoke an Augustinian conception). This propagandistic conception of the Second World War is, in a sense, the mirror image of the Second World War as a great ideological conflict between lofty ideals on the one hand, and, on the other hand, naked evil, belies the pragmatism with which the war was fought and alliances were made, in which the war was rather a conflict driven by geopolitical imperatives — admittedly, geopolitical concerns extrapolated to a planetary scale, but still a conflict more about the distribution of ocean basins and mountain ranges than about ideology. The narrative of the Second World War as “The Good War” that was fought by the “greatest generation” elides the catastrophic policy failures of both the First and Second World Wars, and the peace settlements that followed upon them, which were arguably invidious to the grand strategies of the western nation-states. The Cold War was necessitated by the failed outcome of the Second World War in the same way that the Second World War was necessitated by the failed outcome of the First World War. However, it is at least arguable that the Cold War was fought more effectively than the world wars of the first half of the twentieth century.

The General Assembly of the United Nations Convenes for the first time on 10 January 1946 in London.

The ability of human beings to conceptualize and to act upon planetary-scale ideals is noble and inspiring, but a failure to distinguish between ideals that can be brought into being at the present, and ideals that must wait for another time, when conditions are right for their realization, constitutes a failure of wisdom at least proportional to nobility of conceptualizing an unattainable ideal. When Wilson arrived in Paris in 1919, and when FDR traveled to Yalta in 1945, both American presidents were prepared to make major strategic concessions in order to bring robust international institutions into being, and this willingness to sacrifice US national interests to a larger vision for peace on a planetary scale, following upon war on a planetary scale, put the US at a disadvantage. The outcome could well have been better for all if these presidents had exclusively focused on US national interests and the national interests of US allies rather than upon a trans-national ideal. Other parties to the negotiations in Paris and Yalta cannot be blamed for taking advantage of US willingness to bargain away its interests, and the interests of its allies, in order to secure the future of international institutions, which no one else took seriously. Of course, it must also be noted that both Wilson and FDR believed that the successful implementation of these international institutions would be in the strategic interest of the US, and many would argue that the US, as the leading post-war international power, got at least part of what it bargained for in the form of international institutions.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Tank after One Hundred Years

15 September 2016

Thursday

A Century of Industrialized Warfare:

Mechanized Armor Enters the Fray

On 15 September 1916 one of the pivotal events of industrialized warfare occurred: the tank was used in battle for the first time in history. Mobile fire has been the crucial offensive weapon of warfare since the beginning of civilization and warfare, whether that mobile fire took the form of chariot archers, mounted horse archers, a ship of the line, or mechanized armor, as with the tank. Before industrialized warfare the heaviest armored unit was heavy cavalry (or possibly elephants, though elephants were never armored to the extent that cataphracti or medieval knights were armored), which was a shock weapon — mobile, but not mobile fire. The tank was able to combine mobile fire with heavy armor in a way that no non-mechanized force was capable, and this made it a distinctive feature of industrialized warfare.

The Battle of the Somme had started on 01 July 1916, and with two and half months into the “battle” it was obvious that the Somme would be like most WWI battlefields: largely static and dominated by defense: trenches, barbed wire, and machine gun nests, which had arrested the progress of any offensive and so had precluded decisive attainment of objectives. Up to this time, the technology of the industrial revolution had strengthened the defense, but with the introduction of the tank all that changed. Mechanized armor brought mobile fire into the age of industrialized warfare, and mechanized armor has remained, for a hundred years, the primary spearhead of offensive action.

Despite its initial effectiveness as a “terror weapon,” the pace of tank development was somewhat slow for wartime conditions. The Germans did not introduce their first tank until the A7V was deployed in March 1918, and the first battle between tanks took place during the Second Battle of Villers-Bretonneux in April 1918. Early tanks were mechanically unreliable, and were fielded in smaller numbers than would have been necessary to fundamentally change the conditions of battle. In many ways, this paralleled the use of aircraft during the First World War: the technology was introduced, but not yet mastered.

It was not the introduction of the tank that ended the First World War. However, an adequate conceptualization of mechanized armor began to emerge during the interwar period, when tanks underwent extensive development and testing, and Heinz Guderian wrote his Achtung — Panzer! (much as Giulio Douhet wrote The Command of the Air during the interwar period). The tank truly came into its own during the Second World War, combined with close air support in a highly mobile form of maneuver warfare that came to be called Blitzkrieg. The largest tank battle in history took place during the Battle of Kursk in July 1943, almost thirty years after the tank was first used in combat.

In The End of the Age of the Aircraft Carrier I speculated that armored helicopters could take the place of tanks in a mechanized spearhead. Though helicopters will always be more vulnerable than a tank, because they can never be as heavily armored as tanks, they are today the premier weapon of mobile fire and could press forward the attack far faster than tanks. Helicopter gunships, however, have not yet been fully exploited for battlefield use, partly because they appeared on the scene at a point of time in history when peer-to-peer conflict among nation-states was already a declining paradigm, and so they have filled a very different combat role.

The paradigm of hybrid warfare that is emerging in our own time — a form of warfare probably more consistent with the existence of planetary civilization than the past paradigm of peer-to-peer conflict among nation-states — has no place for heavily armored mobile fire comparable to the place of the tank in twentieth century warfare. The forces now actually engaged in armed conflict (as opposed to appearing in military parades) tend to be lighter, faster, and stealthier. Despite the tendency of warfare to press forward the rapid development of technologies under conditions of existential threat, we have seen that it can take decades to fully assimilate a new technology into warfare, as was the case with the tank. It will probably take decades to get beyond doctrines of mechanized warfare established in the twentieth century and to adopt a doctrine more suitable for the forces employed today.

. . . . .

. . . . .

A Century of Industrialized Warfare

0. A Century of Industrialized Warfare

4. A Blank Check for Austria-Hungary

5. Serbia and Austria-Hungary Mobilize

6. Austria-Hungary Declares War on Serbia

10. The Somme after One Hundred Years

11. The Tank after One Hundred Years

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Somme after One Hundred Years

1 July 2016

Friday

Today is the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the Battle of the Somme (also called the Somme Offensive), which began on 01 July 1916. The Somme has become symbolic in regard to the military mistakes of the First World War, especially in its wastefulness of human life. On the first day of the battle alone the British lost almost 20,000 killed in action out of a total of 57,470 casualties. This went on for months, with the total casualties for all armies numbering about a million on this one battlefield — the exact number will never be known.

When I first began reading about the First World War I can remember that I was confused about “battles” that went on for months at a time. Verdun, like the Somme, was another “battle” that went on for months. Earlier in history, a battle was a conflict that was usually decided in one day, between sunrise and sunset — a battle possessed the Aristotelian dramatic unities of space, time, and action — and at the most in a few days. The Battle of Gettysburg went on for four days. One can easily make the shift from single day battles of classical antiquity to multi-day battles of the nineteenth century, when the confrontation was more complex, not least because the societies upon which the battle supervened were larger and more complex. But from four days to four months is more of a stretch, and the Battle of the Somme went on for four and half months.

Today we would call military engagements like the Somme or Verdun operations rather than battles, as in The Somme Operation or Operation Verdun. Understanding the Somme (or Verdun) as operations rather than battles places these conflicts on the strategico-tactical continuum, i.e., operational thinking lies between tactical exigencies and strategic thinking, and different talents and a different kind of mind is required for operational planning in contradistinction to tactical action or strategic planning. The fact that we still call The Somme and Verdun “battles” — a usage preserved from the era of the conflict — shows how little these engagements were understood at the time.

As the First Global Industrialized War, World War One involved many new elements unprecedented in warfare, primarily technological innovations. How these technological innovations came together tactically, operationally, or strategically was not understood, and it was not understood for the simple reason that no one had any experience of these technologies on the battlefield. World War One provided this experience, while the interwar period provided time to reflect, and resulted in definitive treatises like Heinz Guderian‘s Achtung – Panzer! and Giulio Douhet‘s Il dominio dell’aria. With the advent of World War Two, military thinking had caught up with industrialized military technology, and the Second Global Industrialized War was very different from the first.

I am sure that memorials will be held on this hundredth anniversary, and speeches will be made. For the most part, the Somme has passed out of living memory and into historical memory. What is the historical memory of the Somme? Today we primarily remember the bloodletting — not any nobility of sacrifice or military glory, not any technological innovation or bold idea. What we remember is the human toll.

Recently I learned a term for the human toll of conflict, “hemoclysm,” used by Matthew White to describe the mass bloodletting that was characteristic of the twentieth century — “A violent and bloody conflict, a bloodbath; specifically (chiefly with capital initial), the period of the mid-twentieth century encompassing both world wars” — and which specially marks the Somme. Unfortunately, the Somme no longer stands out for its human toll. During the Second World War there were far higher casualty totals for single days, mostly civilians killed when entire cities were destroyed in a single day or a single night, which is something like a return to the paradigm of warfare according to the Aristotelian unities — although we can no longer call these slaughters “battles” in good conscience, so, in this sense, they diverge from the classical warfare paradigm, as they also diverge in primarily resulting in the deaths of civilians.

Total numbers of casualties increased until World War Two, after which they began to decline — something I identified in an early blog post as the “lethality peak.” However, this steady decline in lethality — partly a result of improving technology and precision weapons, but also partly a result of changing human attitudes to industrialized slaughter — took place against the backdrop of the Cold War, i.e., the possibility of nuclear war, with its ever-present possibility of a greater number of casualties in a shorter period of time than any possible conflict with conventional weapons. If humanity every fights a full scale nuclear war, the casualties will be orders of magnitude greater than our conventional wars.

We call nuclear weapons “strategic weapons” as a concession to their limited utility in actual warfighting. The few examples of tactical nuclear weapons that have been built were considered controversial, because they lowered the threshold for nuclear conflict — notwithstanding the fact that the first use of nuclear weapons was as just another weapon of war — the latest innovation from the conveyor belt of new technologies served up by wartime industries pushed to the limit of their capacity. The attempts to “think the unthinkable,” i.e., to think clearly about nuclear weapons, most famously made by Herman Kahn, were primarily strategic reflections. However, we know that NATO would not pledge “no first use” of nuclear weapons during the Cold War, as the last line of defense for a massive Warsaw Pact tank invasion of western Europe would have been the use of battlefield nuclear weapons, so some tactical doctrine for nuclear weapons would have been worked out, but it is not likely to come to light for some decades.

Nuclear weapons today, like machine guns and barbwire, airplanes and mobile armor a hundred years ago in 1916, remain a technology not yet assimilated to warfighting, and for good reason. The possibilities of nuclear weapons have lain fallow because the powers possessing nuclear weapons have recognized that their use must not be allowed while their escalation would result in our extinction as a species. In other words, our planetary endemism made nuclear war suicidal. This may change eventually.

If I am right that the native range of an intelligent species is not the single world of planetary endemism, but to be distributed across many worlds, the weapons systems that we can today imagine but choose not to build in the interest of our survival may be seen to have a military utility that they do not possess today. When we have a full tactical, operational, and strategic doctrine worked out for nuclear weapons and their delivery systems, we may see a conflict played out on a scale that dwarfs twentieth century world wars as twentieth century world wars dwarfed all previous conflicts.

. . . . .

. . . . .

A Century of Industrialized Warfare

0. A Century of Industrialized Warfare

4. A Blank Check for Austria-Hungary

5. Serbia and Austria-Hungary Mobilize

6. Austria-Hungary Declares War on Serbia

10. The Somme after One Hundred Years

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Sunday

Air Force Space Command General John E. Hyten has announced the release of a new “Commander’s Strategic Intent” document (Commander’s Strategic Intent), which is a 17-page PDF file. Once you take away the front and back covers, and subtract for the photographs inside, there are only a few pages of content. Much of this content, moreover, is the worst kind of contemporary management-speak (the sort of writing that Lucy Kellaway of the Financial Times takes a particular delight in skewering). In terms of strategic content, the document is rather thin, but with a few interesting hints here and there. In a strange way, reading this strategic document from the Air Force Space Command is not unlike the Taliban annual statements formerly issued under Mullah Omar’s name (cf. 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015). One must read between the lines and past the rhetoric in an attempt to discern the reality beneath and behind the appearances. But strategic thought has always been like this.

After a one page Forward by General Hyten, there follows a page each on a summary of the contemporary strategic situation, priorities, mission, vision, Commander’s Intent, Strategy — Four Lines of Effort, and two and a half pages on “Reconnect as Airmen and Embrace Airmindedness,” then several pages with bureaucratic titles but interesting strategic content, “Preserve the Space and Cyberspace Environments for Future Generations,” “Deliver Integrated Multi-Domain Combat Effects in, from and through Space and Cyberspace,” and “Fight through Contested, Degraded and Operationally-Limited Environments,” eith a final page on “You Make a Difference, Today and Tomorrow.”

Strategic Situation

This section rapidly reviews the improving capabilities of adversaries, who are responding to technological and tactical innovations continually introduced by US armed forces in the field. While the document never explicitly mentions hybrid warfare, this is the threat that is clearly on the minds of those formulating this document. While noting the continued dominance of US forces in the global arena, the document mentions that this is, “an era marked by the rapid proliferation of game-changing technologies and growing opportunities to use them,” which is a central problem that will be further discussed below, and for which the document offers no strategic or systematic response (other than the commander’s overall strategic intent).

This survey of the strategic situation also mentions, “new international norms,” which I assume is an internal reference to the central strategic idea of this document discussed below in terms of norms of behavior intended to discourage adventurism that could compromise the global flow of commerce and information. If any new idea about norms of behavior are intended to be a part of the commander’s strategic intent, they are not formulated in this document. I would have left out these references to norms of behavior unless the idea were further developed in an independent section of the document.

Priorities

The priorities listed are three:

Win today’s fight

Prepare for tomorrow’s fight

Take care of our Airmen and our Families

A paragraph is devoted to each priority. The first two are sufficiently obvious. The last introduces a theme that is dominant in this document: the social context of the soldier. One way to look at this is that, in a political context in which it is not possible to raise the wages of soldiers to equal those of the professional class, one benefit that the institutional military can confer on the solider in lieu of higher pay is institutional support for the soldier and his family. An equally plausible interpretation, and perhaps an equally valid explanation, is that, given the technological focus of the Air Force, and especially Space Command, it would be easy to prioritize machinery over soldiers, or to give the impression that machinery has been prioritized over soldiers. Sending the explicit message that, “Airmen — not machines — deliver effects,” is to unambiguously prioritize the soldier over the machinery. (All of this is delivered in the nauseating language of social science and management-speak, but the meaning is clear enough regardless.) And with suicides among returning veterans as high as they are, the military knows that it must do better or it risks losing the trust of its warfighters.

Mission

The mission statement is predictable and uninspiring:

Provide Resilient and Affordable Space and Cyberspace Capabilities for the Joint Force and the Nation.

There is, however, one interesting thing on this page, which is the idea that “Resilience Capacity” is to be used as a metric for combat power. I have written about similar matters in Combat Power and Battle Ecology and Metaphysical Ecology Reformulated, especially as these concerns relate to the social context of the soldier (in the present case, the airman). One hint is given for how this is to be quantified: “Any capability that cannot survive when facing the threats of today and the future is worthless in conflict.” Certainly this is true, but how rigorously this principle can be applied in practice is another question. If everything that failed when exposed to actual combat conditions were to be ruthlessly rooted out, the military would be radically different institution than it is today. Is the Space Command ready for radical application of resilience capacity? I doubt it; it cannot alone defy the weight of institutional inertia possessed by all bureaucracies.

Vision

The vision statement is as lackluster as the mission statement:

One Team—Innovative Airmen Fighting and Delivering Integrated Multi-Domain Combat Effects across the Globe.

This is the kind of management-speak rhetoric that brings documents like this into ill repute, and deservedly so. Moreover, this page makes the claim that, “The three strategic effects of Airpower — Global Vigilance, Global Reach, and Global Power — have not changed.” This is exactly backward. Global vigilance, global reach, and global power are not effects of airpower, but causes of airpower. Such an elementary conceptual failure is inexcusable, but in this context I think it stems more from a desire to employ management-speak in a military context than from pure conceptual confusion. Despite these problems, this page introduces the phrase “aerospace nation,” which is a way to collectively refer to the soldiers and support staff who make aerospace operations possible (presumably also private contractors), and again drives home the message of the social context of the soldier and the institutional support for this social context.

Commander’s Intent

It is a little surprising to read here about the need to, “reconnect with our profession of arms,” which is as much as to admit that there has been a failure to maintain a robust connection with the profession of arms. This is a theme that connects with the support for the social context of the soldier. Part of this social context is home and family, part of this is support staff, and part of it is those directly involved in the profession of arms (i.e., the human ecology of the soldier). Reconnecting with the profession of arms is one method of strengthening the social context of the soldier and therefore the whole of the “aerospace nation.”

Strategy — Four Lines of Effort

So here are the four lines of effort:

• Reconnect as Airmen and Embrace Airmindedness

• Preserve the Space and Cyberspace Environments for Future Generations

• Deliver Integrated Multi-Domain Combat Effects in, from, and through Space and Cyberspace

• Fight through Contested, Degraded, and Operationally-Limited Environments

These themes occur throughout the document, but one can’t call this a strategy. It does, however, qualify as guidance for shaping the policy of Air Force Space Command. But policy must not be mistaken for strategy. Any bureaucrat can make policy, but bureaucrats don’t fight and win wars.

Reconnect as Airmen and Embrace Airmindedness

Now “airmindedness” is an awkward neologism, but it does represent an attempt to represent the qualities needed for the “aerospace nation.” These qualities are difficult to define; this document defines them awkwardly (like its neologisms), but at least it makes an attempt to define them. That is to say, this document makes an attempt to define the distinctive institutional culture of the Air Force Space Command. There is a value in this effort. This is what, if anything, distinguishes the Air Force Space Command from the other branches of the armed services. The need to reconnect with the profession of arms and at the same time to foster the distinctive qualities necessary to aerospace operations, which means pushing the boundaries of technology, constitute a unique challenge for a large, bureaucratic institution (which is what the peacetime military is).

If I had written this I would emphasized the need to continually update and revise any conception of what it means to engage in aerospace operations, hence “airmindedness.” This document focuses on “airmindedness” by emphasizing “shared core values,” innovation, the self-image of the airman as a combatant, development of expertise, resilience capacity (which in this context seems to mean taking care of the individual airman), and supporting the families of airmen while the latter are deployed. While these are all admirable aims, even essential aims, it is astonishing how many of these strategic statements read like social science documents of a Carl Rogers person-centered kind. I would have aimed at conceptually surprising the target audience of this document so that they could see these challenges in a new light, rather than through the lens of boilerplate management-speak.

Preserve the Space and Cyberspace Environments for Future Generations

Strategically, this is perhaps the most important part of the document. In four admirably short paragraphs, this page systematically lays out the the large-scale vision of deterring the outbreak of war, or triumphing in the event that war breaks out. Here, finally, we have a strategy: free flow of commerce and information, deterring adventurism that would compromise the free flow of commerce and information, influencing international norms of behavior in order to deter adventurism, “dissuade and deter conflict” by fielding “forces and capabilities that deny our adversaries the ability to achieve their objectives by imposing costs and/or denying the benefits of hostile actions…” I would have put this section front and center in the document, and connected all the other themes to this central strategy.

Deliver Integrated Multi-Domain Combat Effects in, from and through Space and Cyberspace

This section of the document addresses the technological underpinnings of the strategy announced in the previous section, and so can be considered its tactical implementation on a technological level. Such an emphasis fits in well with the idea of “airmindedness” as a distinctively innovative approach to combat power. But hiding this on page 12 under a section title that is all but incomprehensible is not helpful. The reference to “agility of thought” is belied by the management-speak of the entire document. This agility of thought should extend to the conceptual formulation of what is being done, and how it is being presented.

Fight through Contested, Degraded and Operationally-Limited Environments

This section of the document specifies “four critical activities” that would allow the Air Force Space Command to fight in “Contested, Degraded and Operationally-Limited Environments.” In other words, this is the contemporary approach taken by Space Command to the perennial problem of warfighting that Clausewitz called the “fog of war” (“Nebel des Krieges” — Clausewitz himself used the term “friction,” but this has popularly come to be know as “fog of war”). The document defines these four critical activities intended to mitigate the fog of war as follows:

1. Train to threat scenarios — endeavor to discover the boundaries of our capabilities and constantly reassess those boundaries as threats and blue force capabilities evolve.

2. Identify the timelines and authorities required to successfully defend, fight, and provide effects in today’s and tomorrow’s environments with Operations Centers capable of executing them.

3. Establish the right authorities. For those authorities we control, push the right authorities as far down as possible to ensure timely response.

4. Establish and foster a joint, combined, and multidomain warrior culture that embraces pushing and breaking our operational boundaries and adapting and innovating new doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities, and policy (DOTMLPF-P) solutions.

The friction of combat environments is a real and serious problem for the contemporary technologically-sophisticated warfighting effort — perhaps more of a problem than in the pre-technological age of war. The most sophisticated uses of technology are networked, and sophisticated technology requires continual maintenance and repair. If the first thing that happens in the battlespace is for the network to fail, any battle plan based upon that network will have become irrelevant. How to take advantage of networked information flow while not being captive to the vulnerabilities of such a network is a central problem for warfighting in the technological era. In so far as the Air Force Space Command presents itself as being a uniquely technological capable and competent, this is perhaps the overwhelming challenge to this branch of the military.

Given the centrality of the problem, not surprisingly the document details another seven explicit steps toward attaining the goal of mitigating friction in the technological battlespace. Prefatory to these seven principles the document states, “Our Space Enterprise Vision will capture the key principles needed to guide how we will design and build a space architecture suitable for operations in a contested environment.” No doubt volumes of study have been devoted to this problem internally, and it is admirable that this has been condensed down into seven principles.

As this is intended to be strategic document, I would go a bit farther into the high concept aspect of this problem, and how it could be tackled on the strategic level. What we have seen in recent history is that domains of human endeavor (including warfighting) are utterly transformed when technology becomes cheap and widely available. Adversaries have used this fact asymmetrically against institutionalized armed forces. The strategic approach to being wrong-footed in this way, it seems to me, would be to turn precisely this emerging historical dynamic against asymmetrical forces exploiting this opportunity. How can this be done? A strategy is needed. None is enunciated.

You Make a Difference, Today and Tomorrow

The document closes with a directive to carefully re-read the document and to discuss and to think critically about carrying out the commander’s intent formulated in this statement of principles. There is even an assurance that those who act most fully and faithfully in carrying out this intent will not be punished or put their careers in jeopardy by getting too far out ahead. This observation points to the fundamental tension between the continuous innovation required to keep up with the pace of technological innovation and the inherent friction of any bureaucratic institution. This, too, like the problem of friction in the technological battlespace, is a central problem for the Air Force Space Command, and deserves close and careful study. The definitive strategy to address these two central problems has not yet been formulated.

If I had written this document, I would have had a one paragraph introduction from the general, put the last sections of crucial strategic content first, and reformulated the initial sections so that each section was shown to contribute to and to derive from the central strategic ideas. Beyond that, I would suggest that the institutional challenges faced by Air Force Space Command, recognized in the phase “agility of thought,” points to the need for continual conceptual innovation in parallel with continual technological innovation. The Air Force needs to hire some philosophers.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Status-6 and Nuclear Strategy Beyond the Triad

12 November 2015

Thursday

Accidental leak, or timed disclosure? From a strategic standpoint, it doesn’t really matter, because the weapons system itself is what counts here.

It caused quite a stir today when it was announced that the Russians had accidentally released some details of a proposed submersible weapons system (the Status-6, or Статус-6 in Russian) when television coverage of a conference among defense chiefs broadcast a document being held by one of the participants. This was first brought to my attention by a BBC story, Russia reveals giant nuclear torpedo in state TV ‘leak’. The BBC story led me to Russia may be planning to develop a nuclear submarine drone aimed at ‘inflicting unacceptable damage’ by Jeremy Bender, which in turn led me to Is Russia working on a massive dirty bomb? on the Russian strategic nuclear forces blog, which latter includes inks to a television news segment on Youtube, where you can see (at 1:48) the document in question. A comment on the article includes a link to a Russian language media story, Кремль признал случайным показ секретного оружия по Первому каналу и НТВ, that discusses the leak.

This news story is only in its earliest stages, and there are already many conflicting accounts as to exactly what was leaked and what it means. There is also the possibility that the “leak” was intentional, and meant for public consumption, both domestic and international. There is nothing yet on Janes or Stratfor about this, both of which sources I would consider more reliable on defense than the BBC or any mainstream media outlet. There is a story on DefenseOne, Russia: We Didn’t Mean to Show Everyone Our Massive New Nuclear Torpedo, but this seems to be at least partly derivative of the BBC story.

The BBC story suggested the the new Russian torpedo could carry a “dirty bomb,” or possibly a Colbalt bomb, as well as suggesting that it could carry a 100-megaton warhead. These possible warhead configurations constitute the extreme ends of the spectrum of nuclear devices. A “dirty bomb” that is merely a dirty bomb and not a nuclear warhead is a conventional explosive that scatters radioactive material. Such a device has long been a concern for anti-terrorism policy, because the worry is that it would be easier for terrorists to gain access to nuclear materials than to a nuclear weapon. Scattering radioactive elements in a large urban area would not be a weapon of mass destruction, but it has been called a “weapon of mass disruption,” as it would doubtless be attended by panic as as the 24/7 news cycle escalated the situation to apocalyptic proportions.

At the other end of the scale of nuclear devices, either a cobalt bomb or a 100-megaton warhead would be considered doomsday weapons, and there are no nation-states in the world today constructing such devices. The USSR made some 50-100 MT devices, most famously the Tsar Bomba, the most powerful nuclear device ever detonated, but no longer produces these weapons and is unlikely to retain any in its stockpile. It was widely thought that these enormous weapons were intended as “counterforce” assets, as, given the technology of the time (i.e., the low level of accuracy of missiles at this time), it would have required a warhead of this size to take out a missile silo on the other side of the planet. The US never made such large weapons, but its technology was superior, so if the US was also building counterforce missiles at this time, they could have gotten by with smaller yields. The US arsenal formerly included significant numbers of the B53, with a yield of about 9 MT, and before that the B41, with a yield of about 25 MT, but the US dismantled the last B53 in 2011 (cf. The End of a Nuclear Era).

Nuclear weapons today are being miniaturized, and their delivery systems are being given precision computerized guidance systems, so the reasons for building massively destructive warheads the only purpose of which is to participate in a MAD (mutually assured destruction) scenario have disappeared (mostly). A cobalt bomb (as distinct from a dirty bomb, with which it is sometimes confused, as both a dirty bomb and a cobalt bomb can be considered radiological weapons) would be a nuclear warhead purposefully configured to maximize radioactive fallout. In the case of the element cobalt, its dispersal by a nuclear weapon would result in the radioactive isotope cobalt-60, a high intensity gamma ray emitter with a half-life of 5.26 years — remaining highly radioactive for a sufficient period of time that it would likely poison any life that survived the initial blast of the warhead. The cobalt bomb was first proposed by physicist Leó Szilárd in the spirit of a warning as to the direction that nuclear technology could take, ultimately converging upon human extinction, which became a Cold War touchstone (cf. Existential Lessons of the Cold War).

The discussion of the new Russian weapon Status-6 (Статус-6) in terms of dirty bombs, cobalt bombs, and 100 MT warheads is an anachronism. If a major power were to build a new nuclear device today, they would want to develop what have been called fourth generation nuclear weapons, which is an umbrella term to cover a number of innovative nuclear technologies not systematically researched due to both the end of the Cold War and the nuclear test ban treaty. (On the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty cf. The Atomic Age Turns 70) Thus this part of the story so far is probably very misleading, but the basic idea of a nuclear device on a drone submersible is what we need to pay attention to here. This is important.

I am not surprised by this development, because I predicted it. In WMD: The Submersible Vector of January 2011 I suggested the possibility of placing nuclear weapons in drone submersibles, which could then be quietly infiltrated into the harbors of major port cities (or military facilities, although these would be much more difficult to infiltrate stealthily and to keep hidden), there to wait for a signal to detonate. By this method it would be possible to deprive an adversary of major cities, port, and military facilities in one fell swoop. The damage that could be inflicted by such a first strike would be just as devastating as the first strikes contemplated during the Cold War, when first strikes were conceived as a massive strike by ICBMs coming over the pole. Only now, with US air superiority so far in advance of other nation-states, it makes sense to transfer the nuclear strategic strike option to below the world’s oceans. Strategically, this is a brilliant paradigm shift, and one can see a great many possibilities for its execution and the possible counters to such a strategy.

During the Cold War, the US adopted a strategic defense “triad” consisting of nuclear weapons deliverable by ground-based missiles (ICBMs), jet bombers (initially the subsonic B-52, and later supersonic bombers such as the B-1 and B-2), and submarine launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). Later this triad was supplemented by nuclear-tipped cruise missiles, which represent the beginning of a disruptive change in nuclear strategy, away from massive bombardment to precision strikes.

The Russians depended on ground-based ICBMs, of which they possessed more, but, in the earlier stages of the Cold War Russian ICBMs were rather primitive, subject to failure, and able to carry only a single warhead. As Soviet technology caught up with US technology, and the Russians were able to build reliable missile boats and MIRVs for their ICBMs, the Russians too began to converge upon a triad of strategic defense, adding supersonic bombers (the Tu-22M “Backfire” and then the Tu-160 “Blackjack”) and missile boats to their ground-based missiles. For a brief period of the late Cold War, there was a certain limited nuclear parity that roughly corresponded with détente.

This rough nuclear parity was upset by political events and continuing technological changes, the latter almost always led by the US. An early US lead in computing technology once again led to a generational divide between US and Soviet technology, with the Soviet infrastructure increasingly unable to keep up with technological advances. The introduction of SDI (Strategic Defense Initiative) threatened to further destabilize nuclear parity, and which in particular was perceived to as a threat to the stability of MAD. Long after the Cold War is over, the US continues to pursue missile defense, which has been a remarkably powerful political tool, but despite several decades of greatly improved technology, cannot deliver on its promises. So SDI upset the applecart of MAD, but still cannot redeem its promissory note. This is an important detail, because the weapons system that the Russians are contemplating with Status-6 (Статус-6) can be built with contemporary technologies. Thus even if the US could extend its air superiority to space, in addition to fielding an effective missile defense system, none of this would be an adequate counter to a Russian submersible strategic weapon, except in a second strike capacity.

As I noted above, there would be many ways in which to build out this submersible drone strategic capability, and many ways to counter it, which suggests the possibility of a new arms race, although this time without Russia being ideologically crippled by communism (which during the Cold War prevented the Soviet Union from achieving parity with western scientific and economic strength). A “slow” strategic capability could be constructed based something like what I described in WMD: The Submersible Vector, involving infiltration and sequestered assets, or a “fast” strategic capability closer to what was revealed in the Russian document that sparked the story about Status-6, in which the submersibles could fan out and position themselves in hours or days. Each of these strategic assets would suggest different counter measures.

What we are now seeing is the familiar Cold War specter of a massive nuclear exchange displaced from our skies into the oceans. If the Russians thought of it, and I thought of it, you can be certain that all the defense think tanks of the world’s major nation-states have thought of it also, and have probably gamed some of the obvious scenarios that could result.

It is time to revive the dying discipline of nuclear strategy, to dust off our old copies of Kahn’s On Thermonuclear War and On Escalation, and to once again think the unthinkable.

. . . . .