Happiness: A Tale of Two Surveys

4 October 2020

Sunday

The happy people of Togo.

The World Happiness Report has been published for every year since 2012 (with the exception of there being no WHR for 2014) by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network. A number of influential persons are involved in the report (e.g., the economist Jeffrey Sacks), there is big money behind the effort (e.g., sponsorship from several foundations and companies), and there are several major universities associated with the effort (Columbia, UBC, LSE, Oxford). Of course, the UN is involved also, via the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, and the report itself incorporates extensive discussions of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Each year when the WHR is published there are predictably celebratory reports in the legacy media, along with the equally predictable hand-wringing and pearl-clutching in regard to the countries that occupy the bottom of the list.

Happy children in Togo.

With so much talent and money and reputation involved, the report not surprisingly has a sophisticated methodology. Indeed, the methodology is so sophisticated that it might be called “opaque”; I had to spend quite a bit of time reading the fine print to figure out how it was that they were coming up with their happiness rankings. Of course, the reports in the media feature the rankings, and only the merest cursory description of the methodology. In this, the WHR is incredibly effective in promoting a narrative of national success and failure without many people looking into the guts of their happiness machinery.

More happy people in Togo.

The WHR each year starts out with an explanation of the Cantril Ladder, which seems prima facie to be a relatively straight-up measure of subject well-being. The Cantril Ladder asks survey participants, “…to value their lives today on a 0 to 10 scale, with the worst possible life as a 0 and the best possible life as a 10.” (2015 WHR, p. 20) The Cantril Ladder, however, is only the beginning of the fun. The number they derive from the Cantril Ladder question is then run through six different equations, each of which brings another factor into the “happiness” calculation. The six additional factors are “GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make life choices, generosity, and freedom from corruption.” (p. 21)

More happy children in Togo.

Of these six factors, two — per capita GDP and healthy life expectancy — are “hard” numbers for economists (in other words, they are relatively hard numbers, but these numbers can be gamed as well). Two factors require additional questions that probe subjective well-being, and these are social support and freedom to make life choices. To assess social support respondents were asked, “If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not?”; to assess freedom to make life choices, respondents were asked, “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your freedom to choose what you do with your life?” The remaining two factors are a bit squishy — generosity and freedom from corruption — by which I mean that there are measurements that could be taken for these, but subjective perceptions can also be involved. To measure generosity respondents were asked, “Have you donated money to a charity in the past month?” This strikes me as a good metric. To measure corruption respondents were asked, “Is corruption widespread throughout the government or not?” and “Is corruption widespread within businesses or not?” This strikes me as much less satisfactory, especially since bodies like Transparency International have made an effort to compile corruption indices, but it is a good measure in so far as it is more self-reported well-being data.

Yet more happy people in Togo.

Once the numbers are crunched according to their formulae, the 2015 WHR ranks the following as the ten happiest countries in the world:

1. Switzerland (7.587)

2. Iceland (7.561)

3. Denmark (7.527)

4. Norway (7.522)

5. Canada (7.427)

6. Finland (7.406)

7. Netherlands (7.378)

8. Sweden (7.364)

9. New Zealand (7.286)

10. Australia (7.284)

One cannot but notice that these are all western, industrialized nation-states, mostly European, and indeed mostly northern European.

More happiness in Togo.

In the same 2015 WHR, Togo comes in dead last. Do I believe that the people of Togo are the least happy on Earth? No, I don’t. However, I do believe that well-meaning philanthropic foundations believe that Togo needs to change, and that it especially needs the “help” of these philanthropic foundations to better acquaint them with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, so that they, too, can be made as happy as the northern European countries that top the WHR. I’m certainly not saying that everything in Togo is fine and dandy. There was serious political unrest in the country in 2017-2018 (cf. 2017–2018 Togolese protests), but, given what we delicately call the “social unrest” in the US during the summer of 2020 (also known as riots, vandalism, looting, arson, assault, and murder), I’m not sure that things are worse in Togo than the US, even if Togo is objectively impoverished compared to the US.

“Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy.”

Now, being myself from northern European stock (Norwegian on my father’s side and Swedish on my mother’s side), I could point with pride to the narrative of national success for Scandinavia that is a common feature of international comparisons of this kind, except that, being culturally Scandinavian, and having traveled in these countries, I know what the people are like. I feel very familiar in this context, and, frankly, I enjoy being in Scandinavia and being among other Scandinavians, with whom I share much in terms of temperament and attitude to life. I have also traveled in southern Europe and experienced the very different pace and temper of life, as well as the different pace and temper of life in South America, where I have traveled extensively. I have not (yet) had the good fortune to travel in Africa, much less to Togo itself, so I cannot speak from personal experience in regard to these peoples, but I do not doubt that they possess a full measure of well-being and life satisfaction such as only could be expressed in terms of their culture, much as well-being and life satisfaction in Scandinavia is expressed in terms of Scandinavian culture. What passes for “happiness” among wealthy, industrialized, Nordic peoples of a stoic disposition is not necessarily what would pass for “happiness” among west Africans.

Good times in Togo.

I have focused on the 2015 WHR report (which is not the most recent) because it provides an interesting contrast to another report from 2015, which is the WIN/Gallup International annual global End of Year survey. WIN/Gallup International collaborated on these annual surveys for ten years, from 2007 to 2017. Both WIN and Gallup International are still in business, but they no longer collaborate on these annual surveys; Gallup International (GIA) is not be confused with Gallup Inc., which two are distinct polling companies. The annual End of Year (EoY) surveys can be on a variety of questions (for 2018 the EoY survey was on political leadership), but happiness has been the focus of polling on several occasions. With these EoY surveys, Gallup International takes a sample of about 1,000 persons each from about 60 countries, always including the G20 plus a sampling of other nation-states that together represent better than half of the global population.

Togolese bananas

The methodology of the WIN/Gallup International EoY 2015 survey on happiness was a lot simpler than than Byzantine methodology of the 2015 WHR. WIN/GIA asked three questions:

● Hope Index: As far as you are concerned, do you think that 2016 will be better, worse or the same than 2015?

● Economic Optimism Index: Compared to this year, in your opinion, will next year be a year of economic prosperity, economic difficulty or remain the same for your country?

● Happiness Index: In general, do you personally feel very happy, happy, neither happy nor unhappy, unhappy or very unhappy about your life?

It is an interesting feature of these questions that the first two are framed in terms of predictions — a better next year and a more prosperous next year — but at bottom all three of these questions are questions that probe the individual’s sense of subjective well-being, albeit well-being sometimes projected into the future. Moreoever, WIN/GIA’s numbers aren’t run through a number of equations that filter these measures of subjective well-being through a variety of other factors.

Home, sweet home, in Togo.

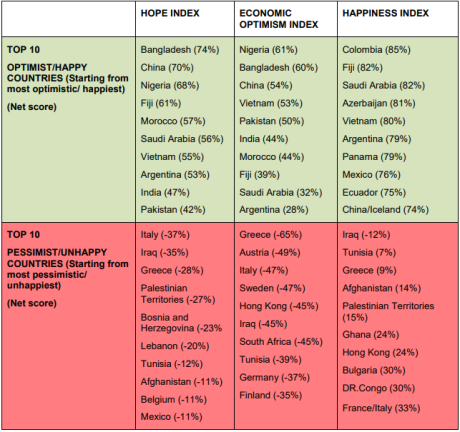

When WIN/GIA crunched their numbers, the top ten rankings of the happiest places on the planet were radically different from those of the WHR, including a significant number of wealthy, industrialized European nation-states ranked in the bottom ten of the hope, optimism, and happiness indices:

1. Colombia (85%)

2. Fiji (82%)

3. Saudi Arabia (82%)

4. Azerbaijan (81%)

5. Vietnam (80%)

6. Argentina (79%)

7. Panama (79%)

8. Mexico (76%)

9. Ecuador (75%)

10. China/Iceland (74%)

We’ve already seen the very different methodologies employed by these two systems of ranking happiness around the world, so we understand how and why they differ, but what exactly does this difference mean? Bluntly, and in brief, it means that if you simply ask people if they are happy, you get results like WIN/GIA; if you run self-reported happiness through a filter of economics, you get results like WHR. Another way to frame this would be to say that the WHR implicitly incorporates Maslovian assumptions built into its rankings, such that a number of physiological and social needs must be met before we can even consider the question of happiness; if we interpret happiness as a form of self-actualization, we can see the relevance of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to sophisticated rankings of happiness that incorporate many other factors.

How much weight should we give to self-reported well-being? Should we be factoring in metrics other than subjectively reported happiness in attempting to measure happiness? Are individuals not their own best judge of their own happiness? There is a certain irony involved in economists assuming that individuals are not their own best judge of their own happiness, as it is economists who are always telling us that individuals are always the best judge of how their own earnings should be spent, because an individual exercises a close and careful oversight over money he himself has earned, while governments collecting money through taxes are spending money they did not themselves earn, and so are likely to exercise less stringent oversight.

More to the point, should elaborate polling methodologies with a pretense to represent self-reported well-being, but which in fact represent economic measures, drive analysis and policy? If we are to take happiness rankings as the basis of policy prescriptions, as the WHR position their study, but using the WIN/GIA numbers instead, then clearly the nation-states of the world should be emulating Colombia, Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, and Argentina. One might then conclude that the way to national happiness is surviving a 50 year civil war, capital punishment by beheadings in the street, having a one-party communist dictatorship, or having the largest sovereign debt default in history. The economists studying happiness would probably see such policy prescriptions as moral hazards. One suspects that the authors of the first WHR in 2012 saw the raw Cantril Ladder data, knew that it wasn’t going to give them the results that they wanted, and realized that they had their work cut out for them. For someone who knows how to crunch numbers, and who could get the raw data from which the WHR is compiled, it would be an interesting exercise to see exactly how much subjective well-being made any difference at all in the rankings.

If we take only per capita GDP in 2015 this is the top ten ranking:

1. Luxenbourg

2. Switzerland

3. Macao SAR

4. Norway

5. Ireland

6. Qatar

7. Iceland

8. US

9. Singapore

10. Denmark

We can immediately see that this list shares four entries with the WHR list — Switzerland, Iceland, Norway, and Denmark — while it shares only one entry with the WIN/GIA rankings — Iceland ties with China for tenth place in the WIN/GIA happiness index. From this we can see that GDP alone is 40% the same as the WHR rankings. To me this makes the WHR look more like factoring in some sense of subject well-being into economic rankings than it looks like factoring some economic data into self-reported happiness. Why not then simply use per capita GDP as a rough approximation for “happiness”? My speculation: economists already have to deal with ideas like homo economicus and the invisible hand, which are routinely chastised as being a vulgarly reductionist approach to the human condition; if happiness is to be characterized in economic terms, it needs to be done with style, verve, and not a little obfuscation if it is going to be carried off successfully in such a climate.

If one is going to indulge in the pleasant fantasy that public policy can be driven by concerns of individual well-being, one needs to be hard-headed about it if one’s policy proposals are to stand half a chance. The kind of people who formulate UN Sustainable Development Goals are content with the rankings of the WHR as a guide to policy, because it affirms their narrative, but the WIN/GIA rankings are effectively “opposite world” for the same people, and certainly not a guide to policy. If the happiest people in the world are to be found in Saudi Arabia and Azerbaijan, and with the people of Bangladesh and Nigeria topping the Hope Index, then UN measures of what constitutes the good life and hope for the future are more than a little off. And the WHR insists on UN Sustainable Development Goals almost to the point of salesmanship.

While I haven’t here fully showed you how the magic trick is done (I lack the expertise for that), I hope that I’ve showed you enough that the next time you see WHR rankings reported in the media, you will be skeptical of the relationship of these rankings to actual human happiness, which is certainly affected by economics, but is not identical with economics, and, moreover, there can be important outliers such that nearly optimal human happiness may occur with little or no relationship to economic measures that we might be tempted to substitute for happiness. Certainly, again, “well-being” is more than happiness, and economics makes a generous contribution to well-being, but when we use “well-being” as a rough synonym for happiness, and then rightly define well-being (in its other sense, not specifically related to happiness) by economic measures, this is the essence of the magic trick, and such a sleight of hand is not to be believed. I should sooner believe that all the people in Togo are miserable than believe that the contribution of happiness to well-being can be artfully dissimulated.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Resentment of the Creative Class

17 May 2020

Sunday

One of the most annoying constructions of contemporary sociology is Richard Florida’s conception of the “creative class.” Florida isn’t necessarily wrong in his claims, and indeed I am sympathetic to some of his arguments, though much of his analysis turns upon taking a naïve conception of creativity and moving the goal posts so that this intuitive conception of creativity comes to be bestowed upon patently uncreative individuals who pad the ranks of the corporate hierarchy. By marginalizing a “Bohemian” creative class and putting at the center of his analysis the suits who congratulate themselves on being creative, he has arguably misconstrued the sources of creativity in society, but that is not what I want to focus on today.

Here is how Florida defines his “creative class”:

“I define the core of the Creative Class to include people in science and engineering, architecture and design, education, arts, music, and entertainment whose economic function is to create new ideas, new technology, and new creative content. Around this core, the Creative Class also includes a broader group of creative professionals in business and finance, law, health care, and related fields. These people engage in complex problem solving that involves a great deal of independent judgment and requires high levels of education or human capital. In addition, all members of the Creative Class — whether they are artists or engineers, musicians or computer scientists, writers or entrepreneurs — share a common ethos that values creativity, individuality, difference, and merit.”

Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class, Revisited, second edition, pp. 8-9

Florida’s use of the phrase “high human capital individuals” (employed throughout his book) begs the question as to who exactly are the low human capital individuals. Needless to say, formulations like this are self-congratulatory to the point of delusion, because no one who uses the phrase “high human capital individuals” believes themselves to be anything other than a high human capital individual. Here Nietzsche is relevant, though what he said of philosophers must now be applied to sociology: It has gradually become clear to me what every great social science up till now has consisted of — namely, the personal confession of its originator, and a species of involuntary and unconscious memoir.

We need not employ Florida’s annoying formulations. Let’s consider another approach to essentially the same idea. Take, for example, Marx’s version of the “creative class”:

“Milton, who wrote Paradise Lost, was an unproductive worker. On the other hand, a writer who turns out work for his publisher in factory style is a productive worker. Milton produced Paradise Lost as a silkworm produces silk, as the activation of his own nature. He later sold his product for £5 and thus became a merchant. But the literary proletarian of Leipzig who produces books, such as compendia on political economy, at the behest of a publisher is pretty nearly a productive worker since his production is taken over by capital and only occurs in order to increase it.”

Karl Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, London et al.: Penguin, 1976, p. 1044

Clearly, Marx here evinces no romantic notions of the creative genius in isolation, praising the Leipzig hack over the genius of Milton. And this is Florida’s conception of “creativity” in a nutshell, nearly indistinguishable from “productivity” as used in contemporary economics. One can imagine in one’s mind’s eye Richard Florida reading this passage from Marx and nodding his head with an odd grin on his face.

Suit-and-tie guys who are “knowledge workers” in their own imaginations, but in who are in reality time-servers in a corporate hierarchy, are the members of the “creative class” who are fulfilling the function that Marx assigned to the Leipzig hack. In other words, the same kind of people who, fifty years ago would have been reading the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal, are the same people who still today are reading the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal, but now they fancy themselves to be part of the “creative class” and they take micro-doses of LSD when they go to Burning Man each year to “unleash” their creativity.

But this is exactly the kind of “creative class” that the global economy wants and needs; Marx had put his finger on something important when he raised the Leipzig hack over Milton. The less creative you are, and the more you have adapted yourself to be a creature of the institutions you are serving, the more successful you will be (according to conventional measures of success) and the more money you will make.

The pedestrian fact of the matter is that industry — whether something as flashy as the film industry or something as prosaic as the energy industry — advances mediocrities to its top positions. Usually the top people are mediocrities with some redeeming qualities, or a hint of limited talent, but still mediocrities. The truly creative types know that mediocrities are being advanced beyond them and taking the top positions in the industry, and that there is nothing that they can do about this. These truly creative types aren’t living the life of the one percent; indeed, they aren’t living the life the ten percent. Most of them make less than six figures, and there are probably many plumbers, sheet rockers, electricians, and truck drivers who make a lot more than them, and who have no massive college debt hanging over their heads.

The Bohemian creatives, the ones actually creating things, find themselves in the position of performing alienated labor at the behest of their corporate masters, who neither understand nor appreciate them. Having failed to learn one of the simplest lessons in life — that you catch more flies with honey than with vinegar — the lowest strata of the creative class spew their resentment at every opportunity. (The dirtbag left today might be thought of as part of a Bohemian fringe of creative types, though at the political end of the creative spectrum.) They are so convinced of their own virtue that they are unable to see or to comprehend that they themselves have become the bitter, punitive gatekeepers that as “creatives” they presume to despise.

Resentment, it seems, flows uphill. By creating a permanently resentful underclass, which is the basis of the entirety of society (because the underclass have the jobs that keep industrialized civilization functioning), the resentful underclass creates a popular culture derived from this pervasive resentment, and this pervasive popular culture resentment eventually finds its way into the routines of comedians, into television, into films, and ultimately into élite cultural institutions, which imagine themselves setting the cultural and aesthetic agenda, but which in fact respond like reactionaries to the authentic energies of the lower classes.

The phenomenon of resentment flowing uphill manifests itself powerfully among the “creative class.” As we have seen, the most creative members of the creative class experience the appearance of fame but the financial reality of entry-level positions, so that they belong to the permanent underclass and its bitterly resentful view of the world, which is a view of the world from the bottom up. They are well aware of their low financial status, and that they do not share in the rewards of the uncreative members of the “creative class.”

Ultimately, the resentment of the creative class and the bourgeoisie becomes, over time, the resentment of the élites, and this is when we know that society is rotten from top to bottom. When those who have been given every advantage and every preferment in life are bitter and angry about their world, clearly something has gone off the rails. Of course, the resentment of the élites is expressed in a distinctive way, filtered through their thinly-veiled dog whistles and symbols, but not only is it there to be seen, as clear as day, but also pervasively present throughout the institutions that they superintend.

Apparently, it isn’t enough to rule the world and to enjoy a standard of living that is the envy of the masses; more than this, one must have the acquiescence of those masses in their subjection to the rule of élites. Mere compliance and conformity is not enough; there is also to be some formal recognition that the élites deserve their status and are making the best choices for the rest of us. (We live in a meritocracy, right?) When this recognition is not forthcoming, we glimpse the resentment of the élites for those they fancy the low human capital individuals.

It is a fascinating commentary on the resentment of the élites who grow out of a “creative class” that Nietzsche’s analysis of ressentiment crucially turns upon creativity:

“The slave revolt in morality begins when ressentiment itself becomes creative and gives birth to values: the ressentiment of natures that are denied the true reaction, that of deeds, and compensate themselves with an imaginary revenge. While every noble morality develops from a triumphant affirmation of itself, slave morality from the outset says No to what is ‘outside,’ what is ‘different,’ what is ‘not itself’; and this No is its creative deed. This inversion of the value-positing eye — this need to direct one’s view outward instead of back to oneself — is of the essence of ressentiment: in order to exist, slave morality always first needs a hostile external world; it needs, physiologically speaking, external stimuli in order to act at all — its action is fundamentally reaction.”

Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, First Essay, section 10

This is a dialectic of creativity, in which creativity has nothing to work on, so it works on nothing — ressentiment is the creation of new values from nothing. It is an ex nihilo morality par excellence. Nietzsche once wrote of the finest flower of ressentiment, as related by Walter Kaufmann:

“Among the exceedingly few discoveries made in recent times concerning the origin of moral value judgments, Friedrich Nietzsche’s discovery of ressentiment as the source of such value judgments is the most profound, even if his more specific claim that Christian morality and in particular Christian love are the finest ‘flower of resssentiment’ should turn out to be false.”

From Walter Kaufmann’s introduction to his translation of On the Genealogy of Morals

Today our finest flower of ressentiment is the resentful élite who rule over us with a bad conscience — the creative class, the powerful, the educated, the well connected, the wealthy — and who never tire of reminding us of how deeply we have disappointed them. This is the kind of contempt that is exhibited when urbanites speak of “white trash” or some such similar social construct that expresses the bitter hatred of the privileged for the downtrodden. Both in the US and the UK, the political parties that formerly represented the interests of the working classes have been transformed in the past half century into parties that represent urbanized professionals, and they do not even bother to veil their contempt for the working class, who now appear to them as a distasteful embarrassment at best, a contemptible mass at worse, fit only to be ridiculed and despised.

In a Nietzschean analysis, one would expect that it would be the creative few who would be de facto Übermenschen, and so possessed of the virtues of the Übermensch — or, if you prefer, the virtù of the Übermensch — therefore these few would be among the least resentful elements in society, because the Übermensch expends his energies. If we were a society dominated by a truly creative class, we should be a society and an economy of supermen, creating new values and spontaneously releasing any pent up energies, but it is ressentiment that rules the present. Why?

The artificiality of our institutions, which demands that the ruling élites must bend the knee to democratic forms and make a pretense to upholding the rule of law that, in theory, binds their actions no less than ours, constitutes the hostile external world against which the ruling élites react, the Other that is Outside and Different. The creative deed of the élites of the creative class is its emphatic “No!” directed against the world from which it seeks to distinguish itself. Robbed of triumphant affirmation, they must rule without appearing to rule, and the reality of power coupled with its seeming denial is creating new values even now, though these are values that only can be savored in submerged and secret places — that is to say, in the hearts of the members of the creative class.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Liberal Conception of Freedom

3 June 2018

Sunday

In my previous post, The Illiberal Conception of Freedom, I attempted to describe a conception of human freedom that has become distant and alien to us, but which was familiar to everyone for the greater part of human history. Much more familiar to us, living after the Enlightenment, is the liberal conception of freedom, which had among its greatest exponents John Stuart Mill. Here is one of his classic statements of the liberal conception of freedom:

“…the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinions of others, to do so would be wise, or even right. These are good reasons for remonstrating with him, or reasoning with him, or persuading him, or entreating him, but not for compelling him, or visiting him with any evil in case he do otherwise. To justify that, the conduct from which it is desired to deter him must be calculated to produce evil to some one else. The only part of the conduct of any one, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others. In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.”

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, I

We can understand the work of John Stuart Mill as part of the Victorian achievement, embodying some of the most trenchant social and political thought of the 19th century, and doing so in admirable Victorian prose that is difficult to quote because Mill’s sentences are long and his paragraphs very long indeed. The passage above is the shortest quote I could tear from context that still carries what I take to be its essential meaning.

It is in Mill that we find some of the most eloquent expressions of human freedom and of the sovereignty, autonomy, and dignity of the individual. These are ideals not only of a conception of freedom peculiar to the Enlightenment, but also perennial ideals of the human spirit, and would probably be recognizable in any age. If we could have transported John Stuart Mill back in time and place him in an earlier social milieu, I suspect he would have had much the same to say, even if in a different idiom.

Even though we can recognize the perennial character of the liberal conception of freedom no less than the perennial conception of the illiberal conception of freedom, the former conception, given eloquent expression by Mill, only fully comes into its own in the modern period, in the context of a social and political milieu that is distinctive to the modern period. And this observation points to an inadequacy in my previous exposition of the illiberal conception of freedom: I failed to place this latter conception in the context of the social milieu and political institutions in which it can best be realized.

That the liberal conception of freedom can only be fully realized in the context of liberal democracy is implied by the fact that both liberal freedom and liberal democracy were ideals expressed by Mill. He was the author not only of On Liberty, but also of On Representative Government. These parallel ideas of the liberal freedom of the individual realized within liberal democracy society are part of the core of the Enlightenment ideal, which is the implicit (and imperfectly realized) central project of contemporary civilization, which could be called Enlightenment civilization.

The illiberal conception of freedom is no less perennial, and could well be realized in the milieu of liberal democratic society, but it would be best realized in the context of a society that understands the meaning of and values the ideals that lie at the center of the illiberal conception of freedom; a society in which the spiritual discipline to attain freedom from the flesh and its appetites is valued above other purposes that an individual might pursue. The ideals of feudalism — as imperfectly realized in actual feudal societies as the Enlightenment is imperfectly realized in our society — constitute the optimal context in which the illiberal conception of freedom could be realized. The chivalric ideal of the knight as an individual who has achieved perfect martial and spiritual discipline (as expressed, for example, in In Praise of the New Knighthood by St. Bernard of Clairvaux) exemplifies the illiberal conception of freedom in a Christian social context.

Both traditional feudal societies and modern Enlightenment societies fall short of their ideals, and the individuals who jointly comprise these societies fall short of the ideals of freedom embodied in each respective social order. That both ideals are imperfectly realized means that there are perversions and corruptions of the illiberal conception of freedom no less than perversions and corruptions of the liberal conception of freedom. We need to say this because it is the nature of an ideal to contrast the ideal to its complement, that is to say, to everything that is not the ideal. This idealistic perspective tends to throw together into one basket everything that deviates from the most pure and perfect exemplification of the one or the other. It would be relatively easy, then, to conflate a perversion or a corruption of the liberal conception of freedom with the illiberal conception of freedom itself, or with a perversion or a corruption of the illiberal conception of freedom. Principled distinctions are important, and must be observed if we are not to lose ourselves in confusion.

Minding the distinctions among varieties of freedom and their corruptions is important because there are substantive differences as well as commonalities. As different as the liberal and illiberal conceptions of freedom are, both are conceptions of freedom realized within a social and political context that optimally actualizes them. There are other varieties of freedom of which this is not the case.

Both the liberal and the illiberal conception of freedom are equally opposed to the anarchic conception of freedom, which could also be called the Hobbesian conception of freedom, which is the freedom that obtains in the state of nature, which is, “…a perpetuall warre of every man against his neighbour…” Or, in more detail:

“Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of Warre, where every man is Enemy to every man; the same is consequent to the time, wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them withall. In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, CHAPTER XIII. OF THE NATURALL CONDITION OF MANKIND

In the state of nature, there is perfect freedom, but this perfect freedom entails the possibility of being deprived of our freedom at any moment by the equally perfect freedom of another, who has the freedom to murder us, as we have the freedom to murder him. This Hobbesian conception of freedom — so terrifying to Hobbes that he thought everyone must give away their rights to a sovereign Leviathan that could enforce limits to this perfect freedom in a state of nature — holds only outside social and political milieux. The liberal and illiberal conceptions of freedom hold only within social miliuex, and each is best realized in a social milieu that reflects the ideals implicit in the respective conception of freedom.

The liberal and illiberal conceptions of freedom, then, have some properties in common, and so are not entirely disjoint. There remains the possibility that an extraordinary individual might exemplify the ideals both of liberal and illiberal freedom, asserting in action the sovereignty, autonomy, and dignity of the individual in both the liberal and illiberal spheres. Mill wrote that, “…over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.” The theorist of illiberal freedom would assert that the individual could never be sovereign over his own body and mind until he had achieved the discipline over body and mind that is the ideal of the illiberal conception of freedom. Realization of the ideal of the liberal conception of freedom, then, may be predicated upon a prior realization of the illiberal conception of freedom.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Illiberal Conception of Freedom

30 May 2018

Wednesday

On 17 April 2018 French President Emmanuel Macron gave a speech to the EU parliament in which he stated, “There is a fascination with the illiberal, that is growing all the time.” Since being elected French president Macron has campaigned passionately and tirelessly for reforms in the EU, and while Macron seems to be pretty “woke” to the actual problems facing the EU, his “solution” to this problem is not anything controversial from an EU standpoint, but rather the familiar EU talking point that, if the EU isn’t working quite as well as way hoped, then the solution is more EU. In other words, Macron is doubling down on the EU. To be fair, Macron is also insisting upon changes in the EU that might make a small difference, but at a time when closer European unity is so controversial that EU leaders don’t dare put it to a popular vote, Macron’s reforms are too little, too late. Nevertheless, he gets a gold star for trying.

Macron’s 17 April 2018 speech wasn’t the only speech in which he cited growing illiberalism as a concern. In his speech to the US Congress on 25 April 2018 he said the following:

“Together with our international allies and partners, we are facing inequalities created by globalization; threats to the planet, our common good; attacks on democracies through the rise of illiberalism; and the destabilization of our international community by new powers and criminal states.”

Last year on Hallowe’en, Macron gave a speech at the European Court of Human Rights which included this:

“We are witnessing a resurgence of authoritarian regimes or a fascination in many parts of Europe for illiberal democracies; in my opinion, it is here that the coherence and strength of the responses to the challenges just mentioned must be built.”

Earlier in the same speech, in speaking of the, “traumatic experience of Europeans” (i.e., the Second World War and its aftermath), Macron said:

“Who could seriously claim that the worst is behind us and that we can afford to dilute the strength of the universal principles which bind us? Who could consider that these risks of illiberal democracy, an inward-looking approach and a surreptitious or assumed undermining of our values and our principles are now far behind us?”

This passage is especially interesting for its explicit contrast of Enlightenment universalism with illiberal democracy, and the connection of illiberal democracy with an “inward-looking approach.”

Macron’s warnings of illiberalism got me to thinking. It would probably be fair to say that I am fascinated with illiberal ideas, so when I heard this coming out of Macron’s mouth it really got my attention. Macron didn’t name names — perhaps he was thinking about Viktor Orbán in Hungary, or perhaps he was thinking about how Hitler came to power democratically — when he warned of “illiberal democracy,” but we can ask ourselves, from a principled standpoint (in contradistinction from particular historical examples), what an illiberal democracy would be. Could we even ask, what an illiberal democracy ought to be? Can we even speak in terms of “ought” when we are talking about something that is being derided as a danger?

Thinking about the possibility of illiberal democracy led me to think about what could be called the illiberal conception of freedom, and with this we find ourselves in the presence of an ancient idea in western thought that has been a touchstone of western civilization — but a touchstone that has been among the traditions that the rise of the Enlightenment has at very least occluded, when it hasn’t actually openly attacked the illiberal conception of freedom. So this is important. This is a crucial point at which the Enlightenment project parts ways with the most ancient sources of the western tradition, and in so far as the Enlightenment project is the central project of contemporary civilization (an argument I intend to make elsewhere, but have not yet formulated in detail), this is one of the points at which the Enlightenment represents a rupture with the past and a new form of civilization derived from this preemption of the previous central project of western civilization.

What is the illiberal conception of freedom? I happened to find a perfect evocation of it in Isaiah Berlin’s essay on Herder, in which Berlin, discussing the Protestant Pietists, writes of, “…above all their preoccupation with the life of the spirit which alone liberated men from the bonds of the flesh and nature.” (Vico & Herder: Two Studies in the History of Ideas, New York: Vintage, 1977, p. 152) There you have it in a nutshell. The traditional conception of human nature is that it is in slavish bondage to the flesh, to nature, to the world, and can only be freed from this bondage through the cultivation of the spirit.

The illiberal conception of freedom is implicit in Plato’s critique of democracy in Book VIII of the Republic. Democracy, according to Plato, in seeking to place personal freedom above and before all else, inevitably degenerates into tyranny because it places demagogues in power who ultimately destroy the institutions that raised them to high office. Freedom thus issues in its opposite. Thucydides’ description of revolution on Corcyra (modern Corfu) in his History of the Peloponnesian War is eerily reminiscent of Plato’s more abstract and theoretical account of the collapse of democracy into tyranny. The Platonic critique of democratic freedom is often formulated as a distinction between true freedom and mere license (which latter is presumably what leads to the ruin of democracies). For a treatment of the positive content of Plato’s conception of freedom cf. Siobhán McLoughlin’s The Freedom of the Good: A Study of Plato’s Ethical Conception of Freedom.

The illiberal conception of freedom is one of the central themes of Spinoza’s Ethics, Part IV of which is “Of Human Bondage,” in which Spinoza seeks to demonstrate (and I do mean demonstrate) that the human will is in bondage to emotion (which in most translations is rendered “affects”). Spinoza opens Part IV with a forthright statement of this thesis:

“Human infirmity in moderating and checking the emotions I name bondage: for, when a man is a prey to his emotions, he is not his own master, but lies at the mercy of fortune: so much so, that he is often compelled, while seeing that which is better for him, to follow that which is worse.”

In Part V of the Ethics, Spinoza attains remarkably heights of eloquence and intellectual nobility in praising the life of the man who can overcome the bondage of his emotional life through the exercise of the intellect. While Spinoza’s formulations are thoroughly rationalistic, his message is essentially the same message of his contemporaries the Pietists, about whom Isaiah Berlin was writing in the passage I quoted above, and who expressed these ideas in a spiritual form rather than a rationalistic form.

With the arrival of the Enlightenment, the idea of a spiritual discipline leading to an inner freedom seemed, if not merely quaint, to be actually opposed to “true” human freedom. Hume, one of the great representatives of the Enlightenment, ridiculed the traditional forms of spiritual discipline in the western tradition:

“Celibacy, fasting, penance, mortification, self-denial, humility, silence, solitude, and the whole train of monkish virtues; for what reason are they everywhere rejected by men of sense, but because they serve to no manner of purpose; neither advance a man’s fortune in the world, nor render him a more valuable member of society; neither qualify him for the entertainment of company, nor increase his power of self-enjoyment? We observe, on the contrary, that they cross all these desirable ends; stupify the understanding and harden the heart, obscure the fancy and sour the temper.”

David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, 1777, Section IX, Conclusion, Part I

It is interesting to compare this famous passage from Hume with a remarkably similarly passage from Spinoza, also in Part IV of the Ethics:

“…it rarely happens that men live in obedience to reason, for things are so ordered among them, that they are generally envious and troublesome one to another. Nevertheless they are scarcely able to lead a solitary life, so that the definition of man as a social animal has met with general assent; in fact, men do derive from social life much more convenience than injury. Let satirists then laugh their fill at human affairs, let theologians rail, and let misanthropes praise to their utmost the life of untutored rusticity, let them heap contempt on men and praises on beasts; when all is said, they will find that men can provide for their wants much more easily by mutual help, and that only by uniting their forces can they escape from the dangers that on every side beset them: not to say how much more excellent and worthy of our knowledge it is, to study the actions of men than the actions of beasts.”

We can see from these two passages that Spinoza and Hume are, at least in some respects, closer to each other than any simplistic contrast between liberal freedom and illiberal freedom would suggest. Spinoza and Hume might find common ground if their shades could discuss the question, but the social context of freedom has radically changed both from that of Spinoza and that of Hume. While the world that Spinoza knew is entirely lost, we can also say that what the Enlightenment was in Hume’s time was not yet what the Enlightenment project has become for us today.

Especially since the middle of the twentieth century, the idea of freedom has come to mean “doing your own thing,” which Plato would have called “license” and which more or less involves indulging the individual’s appetites to their limits and beyond. From a superficial perspective, the liberal conception of freedom has triumphed, and as it has triumphed it has trapped us in the idea of realizing our own “authenticity” (in the language of existentialists) and “self-actualization” (in the language of psychology and psychiatry). And yet, for all the authenticity and self-actualization we have lived through, the psychoanalysts have also diagnosed a condition of the “existential void.” That an existential void would attend the indulgence of human appetites would not have surprised any of the theorists of the illiberal conception of freedom.

Is there any place for or possibility of the illiberal conception of freedom today? Should we regard the illiberal conception of freedom as a relic of traditionalism of which we are best rid? Or is there any perennial wisdom in the idea that may have some applicability to the world today? Has the world changed too dramatically for the individual today to seek inner spiritual perfection (and hence spiritual freedom)? Is the illiberal conception of freedom a retreat from the world, an admission of defeat? Is it necessary to turn from the world in order to cultivate the life of the spirit, or can one remain engaged with world and also with the life of the spirit? I will leave these questions for another time.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Biological Bias

3 March 2018

Saturday

What does it mean to be a biological being? It means, among other things, that one sees the world from a biological perspective, thinks in terms of concepts amenable to a biological brain, understands oneself and one’s species in its biological context, which is the biosphere of our homeworld, and that one persists in a mode of being distinctive to biological beings (which mode of being we call life). To be a biological being is to be related to the world through one’s biology; one has biological desires, biological aversions, biological imperatives, biological expectations, and biological intentions. Human beings are biological beings, and so are subject to all of these conditions of biological being.

When we think in terms of human bias — and we are subject to many biases as human beings — we usually focus on exclusively human biases, our anthropocentrism, our anthropic bias, but we are also subject to biases that follow from the other ontological classes of beings of which we are members. We are human beings, but we are also cognitive beings (i.e., intelligent agents), linguistic beings, mammalian beings, biological beings, physical beings, Stelliferous Era beings, and so on. This litany may be endless; whether or not we are aware of it, we may belong to an infinitude of ontological classes in virtue of the kind of beings that we are.

Another example of a bias to which human beings are subject but which is not exclusively anthropic, is what I have called terrestrial bias. Some time ago in Terrestrial Bias: Thought Experiments I asked, “…is there, among human beings, any sense of identification with the life of Earth? Is there a terrestrial bias, or will there be a terrestrial bias when we are able to compare our response to terrestrial life to our response to extraterrestrial life?” As I write this it occurs to me that a distinction can be made between planetary bias, to which any being of planetary endemism would be subject, and terrestrial bias understood as a bias specific to Earth, to which only life on Earth would be subject. In making this distinction, we understand that terrestrial bias is a special case of planetary bias, which latter is the more comprehensive concept.

Similarly, anthropic bias is a special case of the more comprehensive concept of intelligent agent bias. Again, we can distinguish between intelligent agent bias and anthropic bias, with intelligent agent bias being the more comprehensive concept under which anthropic bias falls. However, intelligent agents could also include artificial agents, who would be peers of human intelligent agents in respect of intelligence, but which would not share our biological bias. The many biases, then, which attend and inform human cognition, are nested within more comprehensive biases, as well as overlapping with the biases of other agents that might potentially exist and which would share some of our biases but which would not fall under exactly the same more comprehensive concepts. In Wittgensteinian terms, there is a complicated network of biases that overlap and intersect (cf. Philosophical Investigations, sec. 66); these biases correspond to a complicated network of ontological classes that overlap and intersect.

Our biological biases overlap and intersect with our other biases, such as our biases as the result of being human (anthropic bias) or our biases in virtue of being composed of matter (material or physical bias). Biological bias occupies a point midway between these two ontological classes. Our anthropic bias is exclusive to human beings, but we share our biological bias with every living thing on Earth, and perhaps with living things elsewhere in the cosmos, while we share our material bias much more widely with dust and gas and stars, except that these latter beings, not being intelligent agents, cannot exercise judgment or act as agents, so that their bias can only be manifested passively. One might well characterize the Platonic definition of being — the capacity to affect or be affected — as the passive exercise of bias, with each class of beings affecting and being affected by other beings of the same class as peers.

I have sought to exhibit and disentangle and overlapping and intersecting of biological baises in a number of posts related to biophilia and biophobia, including:

Not all biases are catastrophic distortions of reasoning. In Less than Cognitive Bias I made a distinction between anthropic biases that characterize the human condition without necessarily adversely affecting rational judgment, and anthropic biases that do undermine our ability to reason rationally. And in The Human Overview I sketched out the complexity of ordinary human communication, which is dense in subtle biases, some of which compromise our rationality, but many of which are crucial to our ability to rapidly reason about our circumstances — a skill with high survival value, and a skill at which human beings excel and which will not soon by modeled by artificial intelligence on account of its subtlety. A tripartite distinction can be made, then, among biases that compromise our reason, biases that are neutral in regard to out ability to reason, and biases that augment our ability to reason.

Our biological biases coincide to a large extent with our evolutionary psychology, and, in so far as our evolutionary psychology enabled us to survive in our environment of evolutionary adaptedness, our biological biases augment our ability to reason cogently and to act effectively in biological contexts — though only in what might be called peer biological contexts, as far as our particular scale of biological individuality allows us to identify with other biological individuals as peers. Our peer biological biases do not allow us to interact effectively at the level of the microbiome or at the level of the biosphere, with the result that considerable scientific effort has been required for us to understand and to interact effectively at these biological scales.

A similar applicability of bias may be true more widely of our other biases, which help us in some circumstances while hurting us in other circumstances. Certainly our anthropic biases have helped us to survive, and that is why we possess them in such robust forms, though they have helped us to survive as a species of planetary endemism. In the event of humanity breaking out of our homeworld as a spacefaring civilization, our anthropic, homeworld, and planetary endemism biases may not serve us as well in cosmological contexts. however, we know what to do about this. The cultivation of science and rigorous reasoning has allowed us to transcend many of our biases without actually losing our biases. Instead of viewing this as a human, all-too-human failure, we should think of this as a human strength: we can, when we apply ourselves, selectively transcend our biases, but when we need them, they are there for us, and they will be there for us until we actually alter ourselves biologically. Thus there is a biological “way out” from biological biases, but we might want to think twice before pursuing this way out, as our biological biases may well prove to be an asset (and perhaps an asset in unexpected, instinctive ways) when we eventually explore other biospheres and encounter another form of biology.

What Carl Sagan called the “deprovincialization” of biology may also take place at the level of human evolutionary psychology. If so, we shouldn’t desire to transcend or eliminate our biological biases as we should desire to augment and expand them in order to overcome what will be eventually learn about our terrestrial and homeworld biases from the biology of other worlds.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

A Natural History of Overview Effects

30 December 2017

Saturday

A Prehistory of the Overview Effect

Among many other contributions, E. O. Wilson is known for the Savannah Hypothesis, according to which human beings are especially suited, both biologically and cognitively, to life on the African savannah, which constituted the environment of evolutionary adaptedness (EEA) for our species. E. O. Wilson discusses this in the chapter “The Right Place” in his book Biophilia, in which he characterized this landscape as, “…the ideal toward which human beings unconsciously strive…” (pp. 108-109). Wilson developed this idea over much of this chapter, writing:

“…it seems that whenever people are given a free choice, they move to open tree-studded land on prominences overlooking water. This worldwide tendency is no longer dictated by the hard necessities of hunter-gatherer life. It has become largely aesthetic, a spur to art and landscaping. Those who exercise the greatest degree of free choice, the rich and powerful, congregate on high land above lakes and rivers and along ocean bluffs. On such sites they build palaces, villas, temples, and corporate retreats. Psychologists have noticed that people entering unfamiliar places tend to move toward towers and other large objects breaking the skyline.”

E. O. Wilson, Biophilia, Harvard University Press, 1984, p. 110 (I encourage reading the entire chapter, all of which is relevant to this discussion.)

In this context, the Savannah Hypothesis places human beings in a position to have an overview of the biome that constituted their EEA, that is to say, an overview of their relevant environment, the environment in which their differential survival and reproduction would mean either the continuation or the extinction of the species. As we know, human ancestors survived in such an environment for millions of years, and anatomically modern human beings passed through a bottleneck in such a landscape.

The African savannah was the landscape that played the most recent, and perhaps the most strongly selective role in the human mind and body, and there would be a high survival value attached to having an overview of this landscape. If we seek out prominences from which to take in a sweeping view, we do so for good reason.

Little Big Histories and Little Overviews

We can think of this biome overview as a “little overview,” which term I introduce in analogy to Esther Quadecker’s use of “little big histories,” that is to say, big histories that trace the development of some small topic (smaller than the whole of the universe) over cosmological time, from the big bang to the present day, and possibility also extending into the indefinite future. In the unfolding of our “little overviews” over time we have a prehistory of the overview effect as it is fully revealed when we see our homeworld from space.

Little overviews have played an important role in human history. The need for security and surveillance has resulted in the need for watchtowers and for the “crow’s nest” on a ship. Many of the most famous castles are built on high escarpments in order to command the view of the region, which, before telecommunications, was the only way in which to have a comprehensive survey. These precariously perched castles are thrilling to the romantic imagination, but they originally had a strategic purpose of giving an overview of a geographical region that was tactically significant in an age of fighting prior to modern technology. Anything that could happen on a battlefield could be taken in at a single glance.

Everyone will recall that the Persian king Xerxes had a throne erected from which we could watch the Battle of Salamis unfold as it happened. Byron immortalized the image in his Don Juan:

A king sate on the rocky brow

Which looks o’er sea-born Salamis;

And ships, by thousands, lay below,

And men in nations;—all were his!

He counted them at break of day —

And when the sun set where were they?

A culturally significant little overview is described in Petrarch’s account in a letter to his father of climbing Mount Ventoux, which is one of the most famous accounts of mountain climbing in western literature:

“…owing to the unaccustomed quality of the air and the effect of the great sweep of view spread out before me, I stood like one dazed. I beheld the clouds under our feet, and what I had read of Athos and Olympus seemed less incredible as I myself witnessed the same things from a mountain of less fame. I turned my eyes toward Italy, whither my heart most inclined. The Alps, rugged and snow-capped, seemed to rise close by, although they were really at a great distance…”

Francesco Petrarch, The Ascent of Mount Ventoux

It is something of a sport among historians to debate whether Petrarch was essentially medieval or already a modern mind in medieval times. Certainly there are intimations of modernity in Petrarch. The fact that Petrarch made his ascent of Mount Ventoux, that is to say, the spirit in which he made the ascent, was modern, though his response to the experience was not modern, but medieval. While on top Mount Ventoux Petrarch pulled out a copy of St. Augustine’s Confessions (a symbol both of antiquity and of Christendom) and opens to a passage that reads, “And men go about to wonder at the heights of the mountains, and the mighty waves of the sea, and the wide sweep of rivers, and the circuit of the ocean, and the revolution of the stars, but themselves they consider not.” Petrarch takes this as a rebuke to the worldliness implicit in his ambition to ascend the mountain, and he concluded his letter on the experience with this thought: “How earnestly should we strive, not to stand on mountain-tops, but to trample beneath us those appetites which spring from earthly impulses.”

With this medieval Christian response to a little overview there is much in common with the Stoic “view from above” thought experiment that I previously discussed in Stoicism, Sensibility, and the Overview Effect — the pettiness and smallness of the ordinary world of affairs, the need to transcend this smallness, the potential nobility of the human spirit in contrast to its actual corruption — though the specifically Christian elements are distinctive to Petrarch and place him a distance away from Marcus Aurelius’ disdain for the filth of the terrestrial life. Augustinian theology had declared the world good because God made it, so that the world could no longer be grandly dismissed as with the Stoics. It is the sinful human soul, and not the world, that is to be rebuked and chastised. This is the spirit that Petrarch brought to his experience of a little overview.

The Modern Overview Effect

We begin to encounter a more fully modern appreciation of little overviews in the earliest accounts of balloon aviation, where we find the distinctive relation between the attainment of a physical overview and a change in cognitive perspective, i.e., the idea that the two are tightly coupled. An early balloon flight pioneer, Fulgence Marion (a pen name used by Camille Flammarion), presents this relation plainly and simply: “We gave ourselves up to the contemplation of the views which the immense stretch of country beneath us presented.” Here the object of contemplate is the overview itself, which Marion describes in rapturous prose:

“The broad plains appeared before our view in all their magnificence. No snow, no clouds were now to be seen, except around the horizon, where a few clouds seemed to rest on the earth. We passed in a minute from winter to spring. We saw the immeasurable earth covered with towns and villages, which at that distance appeared only so many isolated mansions surrounded with gardens. The rivers which wound about in all directions seemed no more than rills for the adornment of these mansions; the largest forests looked mere clumps or groves, and the meadows and broad fields seemed no more than garden plots. These marvellous tableaux, which no painter could render, reminded us of the fairy metamorphoses; only with this difference, that we were beholding upon a mighty scale what imagination could only picture in little. It is in such a situation that the soul rises to the loftiest height, that the thoughts are exalted and succeed each other with the greatest rapidity.”

Fulgence Marion, Wonderful Balloon Ascents, or, the Conquest of the Skies, Chapter III

Petrarch was on the verge of just such an appreciation of the view from Mount Ventoux, one might even say that he felt this appreciation, but then turned from it in order to use the experience as a pretext to return to the Augustinian “inner man.”

Alexander von Humboldt, one of the great synthesizers of scientific knowledge of the 19th century, attempted to provide an explanation of the connection between overviews and cognitive changes. Criticizing Burke’s view that the feeling of the sublime arises from a lack of knowledge, Humboldt argues that past ignorance was responsible for the cosmological errors of antiquity, while our exultation at glimpsing an overview arises from our ability to connect ideas previously separate, so that the cognitive shift in the overview effect is due not to lack of knowledge, but to the expansion and integration of knowledge:

“The illusion of the senses… would have nailed the stars to the crystalline dome of the sky; but astronomy has assigned to space an indefinite extent; and if she has set limits to the great nebula to which our solar system belongs, it has been to shew us further and further beyond its bounds, (as our optic powers are increased,) island after island of scattered nebulae. The feeling of the sublime, so far as it arises from the contemplation of physical extent, reflects itself in the feeling of the infinite which belongs to another sphere of ideas. That which it offers of solemn and imposing it owes to the connexion just indicated; and hence the analogy of the emotions and of the pleasure excited in us in the midst of the wide sea; or on some lonely mountain summit, surrounded by semi-transparent vaporous clouds; or, when placed before one of those powerful telescopes which resolve the remoter nebulae into stars, the imagination soars into the boundless regions of universal space.”

Alexander von Humboldt, Cosmos: Sketch of a Physical Description of the Universe, London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1846, pp. 20-21

After Petrarch, the world was changed by the three revolutions — scientific, political, and industrial — and this changed context made possible the little overviews of Fulgence Marion and Alexander von Humboldt, who did not feel the need, as did Petrarch, to turn away to focus on the human soul and its cultivation of piety and salvation. Science changed the way that human beings understood the world, and their place in the world, so that subsequent mountain climbers saw the view of the world from the top of a mountain against a different conceptual background. Here is Julius Evola’s evocation of his contemplation of a little overview:

“…after the action, contemplation ensues. It is time to enjoy the peaks and heights from our vantage point: where the view becomes circular and celestial, where petty concerns of ordinary people, of the meaningless struggles of the life of the plains, disappear, where nothing else exists but the sky and the free and powerful forces that reflect the titanic choir of the peaks.”

Julius Evola, Meditations on the Peaks, “The Northern Wall of Eastern Lyskamm”

Evola’s attitude here more closely resembles that of the Stoic “view from above” thought experiment than Petrarch’s response to climbing Mount Ventoux, though Evola may have been consciously evoking the Stoic attitude, and was probably also influenced by Nietzsche, who spent much of his adult life in Switzerland and often rhapsodized on the views from mountain peaks.

It was a little overview that led to the explicit formulation of the overview effect, as Frank White described in the first chapter of the book in which he named and explicitly formulated the overview effect:

“My own effort to confirm the reality of the Overview Effect had its origins in a cross-country flight in the late 1970s. As the plane flew north of Washington, D.C., I found myself looking down at the Capitol and Washington Monument. From 30,000 feet, they looked like little toys sparkling in the sunshine. From that altitude, all of Washington looked small and insignificant. However, I knew that people down there were making life-or-death decisions on my behalf and taking themselves very seriously as they did so… When the plane landed, everyone on it would act just like the people over whom we flew. This line of thought led to a simple but important realization: mental processes and views of life cannot be separated from physical location.”

Frank White, The Overview Effect: Space Exploration and the Future of Humanity, third edition, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc., 2014, p. 1

Here the modern overview conception is fully stated for the first time in terms amenable to scientific investigation. There is much that is continuous with the ancient and medieval responses to little overviews, and it may be taken as the telos upon which earlier modern accounts like those of Marion, von Humboldt, and Evola converge.

In the ancient, medieval, and modern responses to the overview effect there is both a common element as well as distinctive elements that derive from each period. In common is the sense of elevation above the merely mundane and of converging upon a “big picture” of the relationship between humanity and its homeworld; the distinctive elements arise from the valuation of our homeworld, of humanity, and the conception of the proper relationship between the two. The ancient response draws heavily upon Platonism, seeing the sublunary world as intrinsically less valuable than the superlunary world of the heavens, and humanity is understood to be the better as it tends toward the latter, and the worse as it tends to the former. The medieval response is to reflect on the meanness of human nature in contradistinction to the grandeur of God’s creation. The modern response, while retaining elements of earlier little overviews, begins to pare away the evaluative aspects to converge upon a theoretical expression of the core of the overview experience.

The Future of Little Overviews

Now that humanity is in possession of the overview effect in its most explicit and complete form, as some human beings have seen our homeworld entire with their own eyes, it might be thought that little overviews belong to the past. This would be misleading. The photographs that have brought the overview effect to millions if not billions of persons have been themselves little overviews — an overview that can be held in one’s hand, and which gives us a sense of the actual experience of the overview effect, without actually experiencing the full overview effect for ourselves (like a picture taken from the summit of a mountain by those who did not make the climb themselves). For the time being, the overview effect for most of us will be this little overview, and it remains to some future iteration of our technology to make this view universally available to those who desire it.

Other little overviews also continue to change our perspective on our world and our relation to the universe. The Hubble telescope deep field images — the Hubble Deep Field (HDF), Ultra Deep Field (HUDF), and eXtreme Deep Field (XDF) — are little overviews of the cosmos entire; little because they are a very small sample of the sky, but an overview more comprehensive than any previous human perspective on the universe. In one glance we can take in thousands of galaxies, many of them, like the Milky Way, with hundreds of billions stars each.

Coming to an understanding of the big picture is likely to involve an ongoing dialectic by which we pass from experiences that present us with a more comprehensive perspective, and which serve as imaginative points of departure to contemplation of the cosmos entire, to little overviews that provide counterpoint to our personal experiences and which fill out the expansion of our imagination with greater detail and greater breadth and diversity than the personal experiences of any one individual. Those who can most seamlessly integrate and understand these sources of overviews as a whole, will come to the most comprehensive perspective that can be reconciled with the details and reality of ordinary experience.

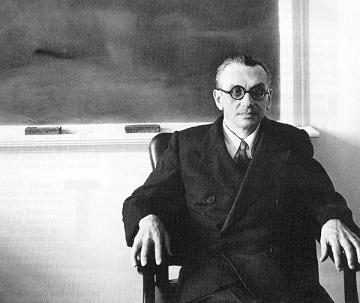

Kurt Gödel 1906-1978

An Overview-Seeking Animal

We have all heard that man is a political animal, or a social animal, or a tool-making animal, and so on. We can add to this litany of distinctive human imperatives that man is an overview-seeking animal. The overviews we have attained, perhaps spurred onward by the evolutionary psychology that E. O. Wilson identified as the Savannah hypothesis, have allowed us to repeatedly transcend our previous perspectives, and with this transcendence of physical perspectives has followed a transcendence of cognitive perspectives, i.e., worldviews or conceptual frameworks. Recently in Einstein on Geometrical Intuition I quoted a passage from Gödel (one of my favorite passages, quoted many times) that is relevant to the transcendence of cognitive perspectives:

“Turing… gives an argument which is supposed to show that mental procedures cannot go beyond mechanical procedures. However, this argument is inconclusive. What Turing disregards completely is the fact that mind, in its use, is not static, but is constantly developing, i.e., that we understand abstract terms more and more precisely as we go on using them, and that more and more abstract terms enter the sphere of our understanding. There may exist systematic methods of actualizing this development, which could form part of the procedure. Therefore, although at each stage the number and precision of the abstract terms at our disposal may be finite, both (and, therefore, also Turing’s number of distinguishable states of mind) may converge toward infinity in the course of the application of the procedure.”

“Some remarks on the undecidability results” (Italics in original) in Gödel, Kurt, Collected Works, Volume II, Publications 1938-1974, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990, p. 306.

The seeking out of overviews, whether little overviews or grand overviews revealing our homeworld entire, is part of the method of actualizing our cognitive development by adding more terms to the sphere of our understanding. What Gödel approached from an abstract point of view the overview effect gives us from a concrete point of view.

. . . . .

. . . . .

Overview Effects

● The Epistemic Overview Effect

● The Overview Effect as Perspective Taking

● Hegel and the Overview Effect

● The Overview Effect in Formal Thought

● Brief Addendum on the Overview Effect in Formal Thought

● Our Knowledge of the Internal World

● Personal Experience and Empirical Knowledge

● The Overview Effect over the longue durée

● Cognitive Astrobiology and the Overview Effect

● The Scientific Imperative of Human Spaceflight

● Planetary Endemism and the Overview Effect

● The Overview Effect and Intuitive Tractability

● Stoicism, Sensibility, and the Overview Effect

● A Natural History of Overview Effects

Homeworld Effects

● The Homeworld Effect and the Hunter-Gatherer Weltanschauung

● Addendum on the Martian Standpoint

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

How to Live on a Planet

27 September 2017

Wednesday

Humanity is learning, slowly, how to live on a planet. What does it mean to live on a planet? Why is this significant? How has our way of living on a planet changed over time? How exactly does an intelligent species capable of niche-construction on a planetary scale go about revising its approach to niche construction to make this process consistent with the natural history and biospheric evolution of its homeworld?

Once upon a time the Earth was unlimited and inexhaustible for human beings for all practical purposes. Obviously, Earth was was not actually unlimited and inexhaustible, but for a few tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of hunter-gatherers distributed across the planet in small bands, this was an ecosystem that they could not have exhausted even if they had sought to do so. Human influence over the planet at this time was imperceptible; our ancestors were simply one species among many species in the terrestrial biosphere. Even before civilization this began to change, as our ancestors have been implicated in the extinction of ice age megafauna. The evidence for this is still debated, but human populations had become sufficiently large and sufficiently organized by the upper Paleolithic that their hunting could plausibly have driven anthropogenic extinctions.

In this earliest (and longest) period of human history, we did not know that we lived on a planet. We did not know what a planet was, the relation of a planet to a star, and the place of stars in the galaxy. The Earth for us at this time was not a planet, but a world, and the world was effectively endless. Only with the advent of civilization and written language were we able to accumulate knowledge trans-generationally, slowly working out that we lived on a planet orbiting a star. This process required several thousand years, and for most of these thousands of years the size of our homeworld was so great that human efforts seemed to not even make a dent in the biosphere. It seemed the the forests could not be exhausted of trees or the oceans exhausted of fish. But all that has changed.