A Decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind

4 July 2019

Thursday

When the Declaration of Independence was signed on 04 July 1776, it was a manifesto to explain, defend, and justify the action of the Founders in breaking from Great Britain and founding an independent political entity. The boldness of this gambit is difficult to appreciate today. Benjamin Franklin said after signing the document, “We must, indeed, all hang together or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.” It was a very real possibility that the Founders would be rounded up and hanged on the gallows. They had signed their names to a treasonous document, which was published for all to read.

Any Royalist with a grudge could have taken down the names of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and used it as a checklist for revenge and retaliation, even if the Founders were successful. And, had the British put down the rebellion, execution would have been certain. Less than a hundred years previously, following the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685, the Bloody Assizes executed hundreds and transported hundreds more to the West Indies under the auspices of Judge Jeffreys, made Lord Chancellor by King James for his services to the crown in the wake of the rebellion. The spirit of the assizes had not subsided, as less fifty years later, the Bloody Assize of 1814 in Canada saw eight executed during the War of 1812 for aiding the Americans. If the revolution had failed, the bloody assizes of 1776 would have been legendary.

To rebel against what the world could only consider a “rightful sovereign” demanded that some explanation be given the world, hence the “decent respect to the opinions of mankind” was a necessary diplomatic move, perhaps the first diplomatic initiative undertaken by what would become the United States of America. But at the same time that a world ruled by monarchs and autocrats, Tsars and Popes, kings and princes, emperors and aristocrats, Caliphs and satraps, would not look kindly upon the rebellion of subject peoples, the Founders could also expect that, in the Great Power competition, other powers would come forward to help the nascent nation simply in order to counter the presumed interests of Britain. The Declaration of Independence provides plausible deniability for any who came to the assistance of the rebels that the cause of the rebels was not mere lèse-majesté that other sovereigns should want to see punished.

The litany of abuses (eighteen items are explicitly noted in the Declaration; item thirteen is followed by nine sub-headings detailing “pretended legislation”) attributed to George III were intended to definitively establish the tyranny of the then-present King of England. I doubt anyone was convinced by the charges made against the British crown. If someone supported the crown or supported the colonies, they probably did so for pretty transparent motives of self-interest, and not because of any abstract belief in the divine right of kings on the one hand, or, on the other hand, any desire to engage in humanitarian intervention given the suffering the colonists experienced as a consequence of the injuries, usurpations, and oppressions of King George III.

King George III made an official statement later the same year, before the Revolutionary War had been won or lost by either side, and the crown’s North American colonies south of Canada might rightly have been said be “in play”: His Majesty’s Most Gracious Speech to Both Houses of Parliament on Thursday, October 31, 1776. A number of newspaper responses to the Declaration of Independence can be found in British reaction to America’s Declaration of Independence by Mary McKee. I don’t know of any point-by-point response to the grievances detailed in the Declaration of Independence, but I would be surprised if there weren’t any such from contemporary sources.

Subsequent history has not had much to say about these specific appeals to a decent respect to the opinions of mankind. The Declaration of Independence has had an ongoing influence, and might even be said to be one of the great manifestos of the Enlightenment, but the emphasis has always fallen on the ringing claims of the first few sentences. These sentences include a number of phrases that have become some of the most famous political rhetoric of western civilization. The litany of grievances, however, have not been among these famous phrases. The idea of taxation without representation occurs in the form of “For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent,” but the more familiar form does not occur in the Declaration.

If the Declaration has intended as plausible deniability for any power that assisted the rebellious colonies, that is not the message that has been transmitted by history. The message that got through was the forceful statement of Enlightenment ideals for political society. In this, the colonies, later the United States, was eventually successful in their appeal to the opinion of mankind. Few today dispute these ideals, even if they act counter to them, whereas other statements of ideals of political society — say, The Communist Manifesto, for instance — have both their defenders and their detractors. It is no small accomplishment to have formulated ideals with this degree of currency.

. . . . .

Happy 4th of July!

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Three Revolutions

12 November 2017

Sunday

Three Revolutions that Shaped the Modern World

The world as we know it today, civilization as we know it today (because, for us, civilization is the world, our world, the world we have constructed for ourselves), is the result of three revolutions. What was civilization like before these revolutions? Humanity began with the development of an agricultural or pastoral economy subsequently given ritual expression in a religious central project that defined independently emergent civilizations. Though widely scattered across the planet, these early agricultural civilizations had important features in common, with most of the pristine civilizations beginning to emerge shortly after the Holocene warming period of the current Quaternary glaciation.

Although independently originating, these early civilizations had much in common — arguably, each had more in common with the others emergent about the same time than they have in common with contemporary industrialized civilization. How, then, did this very different industrialized civilization emerge from its agricultural civilization precursors? This was the function of the three revolutions: to revolutionize the conceptual framework, the political framework, and the economic framework from its previous traditional form into a changed modern form.

The institutions bequeathed to us by our agricultural past (the era of exclusively biocentric civilization) were either utterly destroyed and replaced with de novo institutions, or traditional institutions were transformed beyond recognition to serve the needs of a changed human world. There are, of course, subtle survivals from the ten thousand years of agricultural civilization, and historians love to point out some of the quirky traditions we continue to follow, though they make no sense in a modern context. But this is peripheral to the bulk of contemporary civilization, which is organized by the institutions changed or created by the three revolutions.

The Scientific Revolution

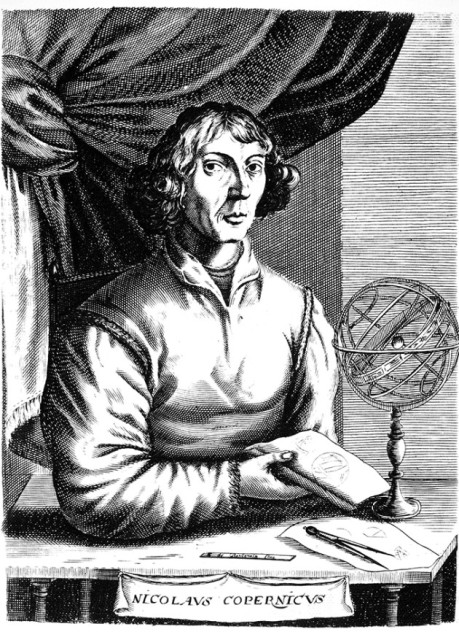

The scientific revolution begins as the earliest of the three revolutions, in the early modern period, and more specifically with Copernicus in the sixteenth century. The work of Copernicus was elaborated and built upon by Kepler, Galileo, Huygens, and a growing number of scientists in western Europe, who began with physics, astronomy, and cosmology, but, in framing a scientific method applicable to the pursuit of knowledge in any field of inquiry, created an epistemic tool that would be universally applied.

The application of the scientific method had the de facto consequence of stigmatizing pre-modern knowledge as superstition, and the attitude emerged that it was necessary to extirpate the superstitions of the past in order to build anew on solid foundations of the new epistemic order of science. This was perceived as an attack on traditional institutions, especially traditional cultural and social institutions. It was this process of the clearing away of old knowledge, dismissed as irrational superstition, and replacing it with new scientific knowledge, that gave us the conflict between science and religion that still simmers in contemporary civilization.

The scientific revolution is ongoing, and continues to revolutionize our conceptual framework. For example, four hundred years into the scientific revolution, in the twentieth century, the Earth sciences were revolutionized by plate tectonics and geomorphology, while cosmology was revolutionized by general relativity and physics was revolutionized by quantum theory. The world we understood at the end of the twentieth century was a radically different place from the world we understood at the beginning of the twentieth century. This is due to the iterative character of the scientific method, which we can continue to apply not only to bodies of knowledge not yet transformed by the scientific method, but also to earlier bodies of scientific knowledge that, while revolutionary in their time, were not fully comprehensive in their conception and formulation. Einstein recognized this character of scientific thought when he wrote that, “There could be no fairer destiny for any physical theory than that it should point the way to a more comprehensive theory, in which it lives on as a limiting case.”

Democracy in its modern form dates from 1776 and is therefore a comparatively young historical institution.

The Political Revolutions

The political revolutions that began in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, beginning with the American Revolution in 1776, followed by the French Revolution in 1789, and then a series of revolutions across South America that displaced Spain and the Spanish Empire from the continent and the western hemisphere (in a kind of revolutionary contagion), ushered in an age of representative government and popular sovereignty that remains the dominant paradigm of political organization today. The consequences of these political revolutions have been raised to the status of a dogma, so that it no longer considered socially acceptable to propose forms of government not based upon representative institutions and popular sovereignty, however dismally or frequently these institutions disappoint.

We are all aware of the experiment with democracy in classical antiquity in Athens, and spread (sometimes by force) by the Delian League under Athenian leadership until the defeat of Athens by the Spartans and their allies. The ancient experiment with democracy ended with the Peloponnesian War, but there were quasi-democratic institutions throughout the history of western civilization that fell short of perfectly representative institutions, and which especially fell short of the ideal of popular sovereignty implemented as universal franchise. Aristotle, after the Peloponnesian War, had already converged on the idea of a mixed constitution (a constitution neither purely aristocratic nor purely democratic) and the Roman political system over time incorporated institutions of popular participation, such as the Tribune of the People (Tribunus plebis).

Medieval Europe, which Kenneth Clark once called a, “conveniently loose political organization,” frequently involved self-determination through the devolution of political institutions to local control, which meant that free cities might be run in an essentially democratic way, even if there were no elections in the contemporary sense. Also, medieval Europe dispensed with slavery, which had been nearly universal in the ancient world, and in so doing was responsible for one of the great moral revolutions of human civilization.

The political revolutions that broke over Europe and the Americas with such force starting in the late eighteenth century, then, had had the way prepared for them by literally thousands of years of western political philosophy, which frequently formulated social ideals long before there was any possibility of putting them into practice. Like the scientific revolution, the political revolutions had deep roots in history, so that we should rightly see them as the inflection points of processes long operating in history, but almost imperceptible in their earliest expression.

Early industrialization often had an incongruous if not surreal character, as in this painting of traditional houses silhouetted again the Madeley Wood Furnaces at Coalbrookdale.

The Industrial Revolution

The industrial revolution began in England with the invention of James Watt’s steam engine, which was, in turn, an improvement upon the Newcomen atmospheric engine, which in turn built upon a long history of an improving industrial technology and industrial infrastructure such as was recorded in Adam Smith’s famous example of a pin factory, and which might be traced back in time to the British Agricultural Revolution, if not before. The industrial revolution rapidly crossed the English channel and was as successful in transforming the continent as it had transformed England. The Germans especially understood that it was the scientific method as applied to industry that drove the industrial revolution forward, as it still does today. It is science rather than the steam engine that truly drove the industrial revolution.

As the scientific revolution drove epistemic reorganization and the political revolutions drove sociopolitical reorganization, the industrial revolution drove economic reorganization. Today, we are all living with the consequences of that reorganization, with more human beings than ever before (both in terms of absolute numbers and in terms of rates) living in cities, earning a living through employment (whether compensated by wages or salary is indifferent; the invariant today is that of being an employee), and organizing our personal time on the basis of clock times that have little to do with the sun and the moon, and schedules that have little or no relationship to the agricultural calendar.

The emergence of these institutions that facilitated the concentration of labor (what Marx would have called “industrial armies”) where it was most needed for economic development indirectly meant the dissolution of multi-generational households, the dissolution of the feeling of being rooted in a particular landscape, the dissolution of the feeling of belonging to a local community, and the dissolution of the way of life that was embodied in these local communities of multi-generational households, bound to the soil and the climate and the particular mix of cultivars that were dietary staples. As science dismissed traditional beliefs as superstition, the industrial revolution dismissed traditional ways of life as impractical and even as unhealthy. Le Courbusier, a great prophet of the industrial city, possessed of revolutionary zeal, forcefully rejected pre-modern technologies of living, asserting, “We must fight against the old-world house, which made a bad use of space. We must look upon the house as a machine for living in or as a tool.”

Revolutionary Permutations

Terrestrial civilization as we know it today is the product of these three revolutions, but must these three revolutions occur, and must they occur in this specific order, for any civilization whatever that would constitute a peer technological civilization with which we might hope to engage in communication? That is to say, if there are other civilizations in the universe (or even in a counterfactual alternative history for terrestrial civilization), would they have to arrive at radio telescopes and spacecraft by this same sequence of revolutions in the same order, or would some other sequence (or some other revolutions) be equally productive of technological civilizations?

This may well sound like a strange question, perhaps an arbitrary question, but this is the sort of question that formal historiography asks. In several posts I have started to outline a conception of formal historiography in which our interest is not only in what has happened on Earth, or what might yet happen on Earth, but what can happen with any civilization whatsoever, whether on Earth or elsewhere (cf. Big History and Scientific Historiography, History in an Extended Sense, Rational Reconstructions of Time, An Alternative Formulation of Rational Reconstructions of Time, and Placeholders for Null-Valued Time). While this conception is not formulated for the express purpose of investigating questions like the Fermi paradox, I hope that the reader can see how such an investigation bears upon the Fermi paradox, the Drake equation, and other “big picture” conceptions that force us to think not in terms of terrestrial civilization, but rather in terms of any civilization whatever.

From a purely formal conception of social institutions, it could be argued that something like these revolutions would have to take place in something like the terrestrial order. The epistemic reorganization of society made it possible to think scientifically about politics, and thus to examine traditional political institutions rationally in a spirit of inquiry characteristic of the Enlightenment. Even if these early forays into political science fall short of contemporary standards of rigor in political science, traditional ideas like the divine right of kings appeared transparently as little better than political superstitions and were dismissed as such. The social reorganization following from the rational examination the political institutions utterly transformed the context in which industrial innovations occurred. If the steam engine or the power loom had been introduced in a time of rigid feudal institutions, no one would have known what to do with them. Consumer goods were not a function of production or general prosperity (as today), but rather were controlled by sumptuary laws, much as the right to engage in certain forms of commerce was granted as a royal favor. These feudal political institutions would not likely have presided over an industrial revolution, but once these institutions were either reformed or eliminated, the seeds of the industrial revolution could take root.

In this interpretation, the epistemic reorganization of the scientific revolution, the social reorganization of the political revolutions, and the economic reorganization of the industrial revolution are all tightly-coupled both synchronically (in terms of the structure of society) and diachronically (in terms of the historical succession of this sequence of events). I am, however, suspicious of this argument because of its implicit anthropocentrism as well as its teleological character. Rather than seeking to justify or to confirm the world we know, framing the historical problem in this formal way gives us a method for seeking variations on the theme of civilization as we know it; alternative sequences could be the basis of thought experiments that would point to different kinds of civilization. Even if we don’t insist that this sequence of revolutions is necessary in order to develop a technological civilization, we can see how each development fed into subsequent developments, acting as a social equivalent of directional selection. If the sequence were different, presumably the directional selection would be different, and the development of civilization taken in a different direction.

I will not here attempt a detailed analysis of the permutations of sequences laid out in the graphic above, though the reader may wish to think through some of the implications of civilizations differently structured by different revolutions at different times in their respective development. For example, many science fiction stories imagine technological civilizations with feudal institutions, whether these feudal institutions are retained unchanged from a distant agricultural past, or whether they were restored after some kind of political revolution analogous to those of terrestrial history, so one could say that, prima facie, political revolution might be entirely left out, i.e., that political reorganization is dispensable in the development of technological civilization. I would not myself make this argument, but I can see that the argument can be made. Such arguments could be the basis of thought experiments that would present civilization-as-we-do-not-know-it, but which nevertheless inhabit the same parameter space of civilization-as-we-know-it.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Revolutionary Republic

4 July 2016

Monday

The title of this post, “The Revolutionary Republic,” I have taken over from Ned Blackhawk from his lectures A History of Native America. No doubt others have used the phrase “revolutionary republic” earlier, but Blackhawk’s lectures were the context in which the idea of a revolutionary republic really struck me. Blackhawk contextualized the American revolution among other revolutionary republics, specifically the subsequent revolutions in France and Haiti. In his book, Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West, Blackhawk has this to say about the Haitian Revolution:

“…in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, contests among New France, New Spain, British North America, and the United States redrew the imperial boundaries of North America in nearly every generation. In 1763, French Louisiana, for example, became part of New Spain. Reverting to France in 1801, it was sold to the United States for a song in 1803 after Haiti’s bloody revolution doomed Napoleon’s ambition to rebuild France’s once expansive American empire.”

Ned Blackhawk, Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West, Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2008, p. 150

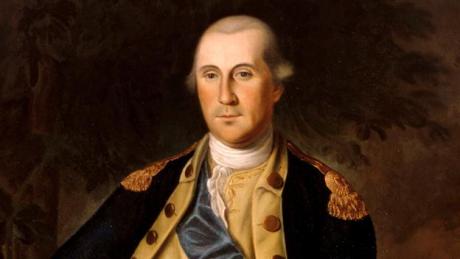

The backdrop of the geopolitical contest that Blackhawk mentions — the “Great Game” of the Enlightenment, as it were — was the Seven Years’ War (what we in the US sometimes call “The French and Indian War,” though this term can be reserved to refer exclusively to the North American theater of the Seven Years’ War), in which future first President of the United States, George Washington, fought as a major in the militia of the British Province of Virginia. The Seven Years’ War is sometimes called the first global war, as it was fought between a British-led coalition and a French-led coalition across the known world at the time.

The Seven Years’ War was the final culmination of imperial conflict between France and the British Empire, and the defeat of the French ultimately led to the triumph of the British Empire and its worldwide extent and command of the seas in the nineteenth century. As an interesting counterfactual, we might consider a world in which the British has triumphed earlier over the French, and had established unquestioned supremacy by the time of the American Revolution. Under these changed circumstances, it would have been even more difficult than it was for the American colonists to defeat the British in the Revolutionary War, and as it was, it was a close-run thing. The colonial forces only won because they fought an ongoing guerrilla campaign against a distant power, which had to project force across the Atlantic Ocean in order to engage with the colonials.

Even at the disadvantage of having to send its soldiers overseas, the British won most of the battles of the Revolutionary War, and the colonials triumphed in the end because they wore down British willingness to invest blood and treasure in their erstwhile colony. When the colonials did win a battle, the Battle of Saratoga, the British made a political decision to cut their losses and focus on other lands of their global empire. From the British perspective, the loss of their American colonies was the price to be paid for empire — an empire must choose its battles, and not allow itself to get tied down in a quagmire among hostile natives — and it was the right decision at the time, as the British Empire was to continue to expand for another hundred years or more. With the French out of the way (defeated by the British in the Seven Years’ War, and then further crippled by the Haitian Revolution, as Blackhawk pointed out), and the American colonies abandoned, the British could move on to the real prizes: China and india.

The Seven Years’ War was the “big picture” geopolitical context of the American Revolution, and the American Revolution itself triggered the next “big picture” political context for what was to follow, which was the existence of revolutionary republics, and panic on the part of the ruling class of Europe that the revolutionary fervor would spread among their own peoples in a kind of revolutionary contagion. One cannot overemphasize the impact of the revolutionary spirit, which struck visceral fear into the hearts of Enlightenment-era constitutional monarchs much as the revolutionary spirit of communism struck fear into the hearts of enlightened democratic leaders a hundred years later. The revolutionary spirit of one generation became the reactionary spirit of the next generation. Applying this geopolitical rule of thumb to our own age, we would expect that the last revolutionary spirit became reactionary (as certainly did happen with communism), while the revolutionary spirit of the present will challenge the last revolutionary regimes in a de facto generational conflict (and this didn’t exactly happen).

The political principles of the revolutionary republics of the Enlightenment came to represent the next great political paradigm, which is today the unquestioned legitimacy of popular sovereignty. All the royal houses that were spooked by the revolutions in the British colonies, France, and Haiti were eventually either themselves deposed or eased into a graceful retirement as powerless constitutional monarchs. So they were right to be spooked, but the mechanisms by which their countries were transformed into democratic republics were many and various, so it was not revolution per se that these regimes needed to fear, but the implacable progress of an idea whose time had come.

. . . . .

Happy 4th of July!

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Scientific Revolutions: Fast and Slow

12 March 2016

Saturday

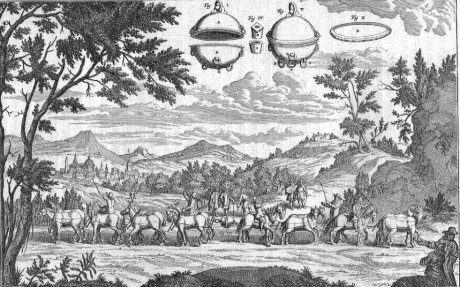

Illustrations from the early scientific revolution bear the stamp of an earlier and other civilization, as in this image, in which as much time has been spent on the trees and the clouds as the scientific experiment itself.

It is a convention of historiography to refer to the formative period of early modern science as “the scientific revolution” (with the definite article), and this is justified in so far as the definitive features of experimental science began to take shape in the period from Copernicus and Galileo to Newton. But in addition to the scientific revolution understood in this sense as a one-time historical process that would not be repeated, there is also the sense of revolutions in science, and there are many such revolutions in science. This sense of a revolution in scientific knowledge has become familiar through the influence of Thomas Kuhn’s book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Kuhn made a now-famous distinction between normal science, which involves the patient elaboration of a scientific research program, and revolutionary science, which involves the shift (a paradigm shift) from an established scientific research program to a new and often unprecedented scientific research program.

Some revolutions in science happen rather rapidly, and some unfold over decades or even centuries. The revolution in earth science represented by geomorphology and plate tectonics was a slow-moving scientific revolution. As long as we have had accurate maps, many have noticed how the coastlines of Africa and South America fit together (a sea captain pointed this out to my maternal grandmother when she was a young girl). When Alfred Wegener put first put forth his theory of plate tectonics in 1912 he had a great deal of evidence demonstrating the geological relationship between the west coast of Africa and the east coast of South America, but he had no mechanism by which to explain the movement of continental plates. The theory was widely dismissed among geologists, but in the second half of the twentieth century more evidence and a plausible mechanism made plate tectonics the central scientific research program in the earth sciences. I have observed elsewhere that Benjamin Franklin anticipated plate tectonics, and he did so for the right reasons, so if we push the origins of the idea of plate tectonics back into the Enlightenment, this is a scientific revolution that unfolded over hundreds of years.

Alfred Wegener recognized fossil patterns over now-separated continents, which suggested a different arrangement of continents in the past, but Wegener had no causal mechanism to explain the movement (map by jmwatsonusgs.gov – United States Geological Survey – http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/continents.htmlen:Image:Snider-Pellegrini_Wegener_fossil_map.gif)

In the past, when knowledge was disseminated much more slowly than it is today, we are not surprised to learn that the full impact of the Copernican revolution unfolded over centuries, while today we expect the dissemination of major scientific paradigm shifts to occur much more rapidly. Indeed, we have the recent example of the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe as a perfect instance of a major and unexpected scientific discovery that was disseminated and accepted by most cosmologists within a year or so.

‘The data summarized in the illustration above involve the measurement of the redshifts of the distant supernovae. The observed magnitudes are plotted against the redshift parameter z. Note that there are a number of Type 1a supernovae around z=.6, which with a Hubble constant of 71 km/s/mpc is a distance of about 5 billion light years.’ (quoted from ‘Evidence for an accelerating universe’ at http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/astro/univacc.html)

The facility with which the accelerating expansion of the universe was assimilated into contemporary cosmology could be used to argue that this was no revolution in science (or it could be said that it was not a “true” revolution in science, which would suggest an application of the “no true Scotsman” fallacy — what Imre Lakatos called “monster barring” — to scientific revolutions). The discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe may be understood as an extension of the revolution precipitated by Hubble, who demonstrated by observational astronomy that the universe is expanding. Since Hubble’s discovery of the expansion of the universe it has assumed that the expansion of the universe was slowing down (a rate of deceleration already given the name of the “Hubble constant” even before the value of that constant had been determined). Hubble’s work was rapidly accepted, but its acceptance was the culmination of decades of debate over the size of the universe, including the Shapley–Curtis Debate, so we can treat this as a slow revolution or as a rapid revolution, depending upon the historical perspective we bring to science.

Harlow Shapley (left) and Heber Curtis (right) debated the structure and size of the universe in a famous confrontation in 1920.

While general relatively came to be widely and rapidly adopted by the scientific community after the 1919 eclipse observed by Sir Arthur Eddington, I have noted in Radical Theories, Modest Formulations that Einstein presented general relativity in a fairly conservative form, and even in this conservative form the theory remained radical and difficult to accept, due to ideas such as the curvature of space and time dilation. After the initial acceptance of general relativity as a scientific research program, the subsequent century has seen a slow and gradual unfolding of some of the more radical consequences of general relativity, which became easier to accept once the essential core of the theory had been accepted.

Einstein formulated his field equations for general relativity in 1915, and we are still deducing the consequences of the theory.

It might be hypothesized that radical theories are accepted more rapidly when a crucial experiment fails to falsify the theory, and the more radical consequences of the theory are fudged a bit so that they do not play a role in galvanizing initial resistance to the theory. If Einstein had been talking about black holes and the expansion of the universe in 1915 he probably would have been dismissed as a crackpot. Another way to think about this is that general relativity appeared as a rigorous, mathematically formalized theory with specific predictions that admitted of crucial experiments within the scope of science at that time. But such a fundamental theory as general relativity was bound to continue to revolutionize cosmology as long as later theoreticians could elaborate the theory initially formulated by Einstein.

Jan Hendrik Oort, for whom the Oort Cloud is named, and an early discoverer of the influence of dark matter on cosmology.

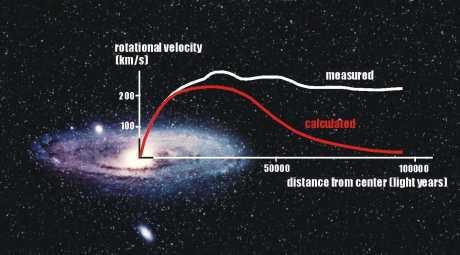

This discussion of slow-moving revolutions in cosmology brings us to the slow moving revolution that is coming to a head in our time. The recognition of dark matter, i.e., of something that accounts for the gravitational anomalies brought to attention by observational astronomy, has been slow to unfold over the last several decades. Two Dutch astronomers, Jacobus Kapteyn and Jan Oort (known for the eponymously-named Oort Cloud, suggested the possibility of dark matter in the early part of the twentieth century. Fritz Zwicky may have been the first person to use the term “dark matter” (“dunkle Materie“) in 1933. Further observations confirmed and extended these earlier observations, but it was not until the 1980s that the “missing” dark matter came to be widely recognized as a major unsolved problem in astrophysics. It remains an unsolved problem, with the best guess for its resolution being the theoretically conservative idea of an as-yet unobserved subatomic particle or particles that can be located within the standard model of particle physics with a minimum of disturbance to contemporary scientific theory.

An elegantly simple demonstration of how dark matter shapes the universe: the rotation curve of spiral galaxies cannot be accounted for by the luminous matter in the galaxy.

There are two interesting observations to be made about this brief narrative of dark matter:

1) The idea of dark matter emerged from observational astronomy, and not as a matter of a theoretical innovation. Established theoretical ideas were applied to observations, and these ideas failed to explain the phenomena. The discovery of the expansion of the universe was also a product of observational astronomy, but it was preceded by Einstein’s theoretical work, which was already accepted at that time. Thus a number of diverse elements of scientific thought came together in a scientific research program for cosmology — a program the pursuit of which has revealed the anomaly of dark matter. There is, at present, no widely accepted physical theory that can account for dark matter, so that what we know of dark matter to date is what we know from observational astronomy.

2) No one has a strong desire to shake up the established theoretical framework either for cosmology or for fundamental physics. In other words, a radical theoretical breakthrough would upset the applecart of contemporary science, and this is not a desired outcome. The focus on dark matter as an undiscovered fundamental particle banks on the retention of the standard model in physics. Much as been invested in the standard model, and science would be more than a little out to sea if major changes had to be made to this model, so the hope is that the model can be tweaked and revised without greatly changing it. One approach to such change would be via what Quine called the “web of belief,” according to which we prefer to revise the outer edges of the web, since changing the center of the web ripples outward and changes everything else. The scientific research program at stake — which is practically the whole of big science today, with fundamental physics just as significant to astrophysics as observational astronomy — is an enormous web of belief, and if you got down to a fine-grained account of it, you would probably find that scientists would disagree as to what is the center of the web of belief and what is the periphery.

I suspect that it may be the case that, the more mature science becomes, the more difficult it will be for a major scientific revolution to occur. Any new theory to replace an old theory must not only explain observations that cannot be explained by the old theory, but the new theory must also fully account for all of the experiments and observations explained by the established theory. Quantum theory and general relativity are the best-confirmed theories in the history of physical science, and for any replacement theory to supplant them, it would have to be similarly precise and well confirmed, as well as being more comprehensive. This is a tall order. Early science picked the low-hanging fruit of scientific knowledge; the more we accumulate scientific knowledge, the more difficult it is to obtain more distant and elusive scientific knowledge. Today we have to build enormous and expensive instruments like the LHC in order to obtain new observations, so each round of expansion of scientific knowledge must wait for the newest scientific instrument to come on line, and building such instruments is becoming extremely expensive and can take decades to complete.

Partly in response to this slowing of the discovery of fundamental scientific principles as science matures, we can seen a parallel change in the use of the term “revolutionary” to identify changes in science. It is somewhat predictable that if a new particle is discovered that can account for dark matter observations, this discovery will be called “revolutionary” even if it can be formulated within the overall theoretical context of the standard model, rather than overturning the standard model. In other words, less is required today for a discovery to be perceived as revolutionary, but, at the same time, it is becoming ever more difficult even to achieve this lower standard of revolutionary change in science. It is extremely unlikely that the macroscopic features of the contemporary astrophysical research program will change, even if the standard model were overturned by a discovery related to dark matter. We will continue to use telescopes and colliders to observe the universe and use computers to run through simulations of incredibly complex models of the universe, so that both observational and theoretical astrophysicists will have a job for the foreseeable future.

. . . . .

Perhaps the most studied avenue to augment the standard model to account for dark matter is the supersymmetry (SUSY) approach, which posits a massive shadow particle for every known particle of the standard model.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

“A republic, if you can keep it.”

4 July 2015

Saturday

Benjamin Franklin, the quintessential American, moved from Boston to Philadelphia and thus inaugurated the quintessentially American tradition of self-reinvention through geographical mobility.

The viability of political entities

There is a well-known story that Benjamin Franklin was asked as he left Independence Hall as the deliberations of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 were in their final day, “Well, Doctor, what have we got — a Republic or a Monarchy?” Franklin’s famous response to this was, “A Republic, madam — if you can keep it.” (The source of this anecdote is from notes of Dr. James McHenry, a Maryland delegate to the Convention, first published in The American Historical Review, vol. 11, 1906.)

The qualification implies the difficulty of the task of keeping a republic together, and keeping it republican. If doing so were easy, Franklin would not have bothered to note that qualification. That he did note it, in the spirit of a witticism, reminds me of another witticism from the American Revolution — quite literally an instance of gallows humor: “Gentlemen, we must now all hang together, or we shall most assuredly all hang separately.” This, too, was from Benjamin Franklin.

The men who fomented the American Revolution, and who went on to hold the Constitutional Convention, were no starry-eyed dreamers. They were tough-minded in the sense that William James used that phrase. They had no illusions about human nature and human society. Their decision to break with England, and their later decision to write the Constitution, was a calculated risk. They reasoned their way to revolution, and they well knew that all that all that they had done, and all that they had risked, could come to ruin.

And still that American project could come to ruin. It is a work in progress, and though it now has some history behind it, as long as it continues in existence it shares in the uncertainty of all human things.

Recently in Transhumanism and Adaptive Radiation I wrote:

“If human freedom were something ideal and absolute, it would not be subject to revision as a consequence of technological change, or any change in contingent circumstances. But while we often think of freedom as an ideal, it is rather grounded in pragmatic realities of action. If a lever or an inclined plane make it possible for you to do something that it was impossible to do without them, then these machines have expanded the scope of human agency; more choices are available as a result, and the degrees of human freedom are multiplied.”

The same can be said of the social technologies of government: if you can do something with them that you cannot do without them, you have expanded the scope of human freedom. The hard-headed attitude of the founders of the republic understood that freedom is grounded in the pragmatic realities of action. It was because of this that the American project has enjoyed the success that it has realized to date. And the freedoms that it facilitates are always subject to revision as the machinery of government evolves. Again, this freedom is not an ideal, but a practical reality.

It is not enough merely to keep the republic, as though preserved under glass. The trajectory of its evolution must be managed, so that it continues to facilitate freedom under the changing conditions to which it is subject. Freedom is subject to contingencies as the fate of the republic is subject to contingencies, and it too can come to ruin just as the republic could yet come to ruin. The challenge remains the same challenge Franklin threw back at his questioner: “If you can keep it.”

. . . . .

Happy 4th of July!

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

One Country, Two Systems, and the Umbrella Revolution

10 October 2014

Friday

It is perhaps too soon to say that the Umbrella Revolution in Hong Kong has failed, but it can be said that the protests have now largely dispersed and the Hong Kong government has already reneged on its promises to hold substantive talks with the student leaders of the protests. The time of greatest danger to the central government in Beijing, and the puppet government it allows to rule in Hong Kong, has passed, and the protesters have had none of their demands met. The government simply had to wait, remain calm, and let the protesters get tired of protesting and go home, which they have mostly done. The government managed this feat simply by waiting and through forbearance, rather than by conducting a massacre, as some feared. Perhaps if the protesters had proved more stubborn, a massacre might have followed in due course, as at Tiananmen.

This was, of course, the unavoidable point of reference for everyone who was watching the protests from afar — and probably also for those participating, and thus putting their lives in danger: the massacre in Tiananmen Square, known in Chinese as the “June 4 Incident.” Everyone wondered of Xi Jinping, “Will he or won’t he?” If we can count it was a “win” for the central government in Beijing that the first phase of protests have passed without granting the demands of the protesters and without the violent suppression of the protests by the PLA, that is indeed to damn the central government with faint praise. And if it was the intention of the protesters to bring the attention of the world to Hong Kong, and the raise the question of whether the proclaimed Chinese policy of “one country, two systems” can work, then the protesters must be judged to have been successful.

The policy of “one country, two systems” is incorporated by the The Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China, says:

“One country, two systems” is the fundamental policy of the Chinese Government for bringing about the country’s reunification. In line with this policy, the Chinese Government has formulated a series of principles and policies regarding Hong Kong. The main point is to establish a special administrative region directly under the Central People’s Government when China resumes its sovereignty over Hong Kong. Except for national defence and foreign affairs, which are to be administered by the Central Government, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region will exercise a high degree of autonomy; no socialist system or policies will be practiced in the Region, the original capitalist society, economic system and way of life will remain unchanged and the laws previously in force in Hong Kong will remain basically the same; Hong Kong’s status as an international financial centre and free port will be maintained; and the economic interests of Britain and other countries in Hong Kong will be taken into consideration.

And…

The rights, freedoms and duties of Hong Kong residents are prescribed in the draft in accordance with the principle of “one country, two systems” and in the light of Hong Kong’s actual situation. They include such specific provisions as protection of private ownership of property, the freedom of movement and freedom to enter or leave the Region, the right to raise a family freely and protection of private persons’ and legal entitles’ property. The draft also provides that the systems to safeguard the fundamental rights and freedoms of Hong Kong residents shall all be based on the Basic Law.

A cynical reading of this text might point out that the first sentence in the above — “One country, two systems” is the fundamental policy of the Chinese Government for bringing about the country’s reunification — speaks only to the reunification of Hong Kong with China, and once that reunification has been achieved what happens in Hong Kong is left ambiguous. The central government in Beijing could maintain that, once a transitional phase of reunification has passed, Hong Kong will be no different from the rest of China, and “one country, two systems” will be a thing of the past.

This is more or less acknowledged in the Basic Law, although on a 50 year horizon, as the Basic Law itself expires on 30 June 2047. This was a sufficiently long time horizon that immediate worries could be allayed, but it turns out the Beijing would like to narrow the interpretation of the Basic Law well before 2047 rolls around. This has been anticipated, as we find in What Will Happen to Hong Kong Kong after 2047?, “…the protections against China eroding one country, two systems even before that date are far less watertight than they appear at first sight… even in this respect, the significance of June 30, 2047 is overstated.”

A familiar talking point in regard to the recent protests in Hong Kong has been the observation that the special arrangements made for the governance of Hong Kong after its handover by the British would be temporary, but extended long enough to accommodate some transition. For optimists, China during this period would open up and become more like Hong Kong, whereas now it appears that the Chinese leadership in Beijing has no interest whatsoever in opening up China in terms of social and political reform, and the period of adjustment is there simply to give Beijing time to force Hong Kong into conformity with the mainland.

How are we to understand an international trading entrepôt to be humbled under the yoke of a skittish Beijing, more concerned with asserting its control than with enjoying the benefits that accrue through a major Port with international connections, strong rule of law, and a significant banking industry? I used “humbled” here advisedly. In order to fully understand the situation of Hong Kong it must be understood in its historical and cultural context. Mainland Chinese who come to Hong Kong as tourists tell of being shabbily treated by the people of Hong Kong, who will make no attempt to speak Mandarin. If you cannot speak Cantonese, you had better try broken English.

We should not be surprised by this. Hong Kong has been a successful, entrepreneurial, cosmopolitan, and indeed an international city. The citizens of such a city would be understandably conscious of their differentness from the un-cosmopolitan mainland Chinese who visit Hong Kong in order to see the “big city.” Any people who have been proud, successful, independent, and, of course, overbearing also in light of their position, are going to invite resentment and a thinly-concealed desire to bring them down to a level with their current condition (to paraphrase from Thucydides). And at the bottom of most communist revolutions of the twentieth century we must remember there was a harnessing of social, cultural, and economic ressentiment, the use of the masses to overthrow the privileged — the expropriation of the expropriators. While “socialism with Chinese characteristics” has by now merely become a screen for crony capitalism, the mobilization of resentment continues to be an effective strategy for the manipulation of mass man by regimes with a communist pedigree.

Neither the pride of the successful, the popular desire to humble the proud, nor the readiness of communist regimes to mobilize popular resentment should be new to anyone. There is a reason that everyone who could afford to get out of Hong Kong got out while the getting was good. A great many former Hong Kong residents moved across the Pacific to Vancouver, British Columbia, and this has resulted in a steady stream of interesting news stories as Vancouver adjusts to its massive influx of wealthy Chinese. Just recently, for example, there was a controversy over advertisements in Vancouver that appeared only in Chinese (cf. Chinese-only sign stirs language controversy in Richmond, B.C.).

But the pre-1997 exodus from Hong Kong is not likely to be followed by a further exodus after Beijing’s decision to further tighten its grip on Hong Kong. There is an economic wrinkle in the story that makes it different from historical parallels. People will not necessarily leave Hong Kong in droves, and even if mainland Chinese could escape from China by passing through Hong Kong, they are not likely to do so in droves; Hong Kong in 2014 is not Berlin in the 1950s. After the Second World War, Germans in East Germany under communist rule could escape through Berlin until the Berlin wall was erected in 1961. And while many of these refugees wanted to escape to the west for freedom, many also wanted to escape the dismal economic regime of East Germany. These forces are not in play in today’s China and Hong Kong. On the contrary, the opposite forces are in play.

Economic refugees are now traveling in the opposite direction, with expatriate Chinese who have lived in the west, and enjoyed its personal freedoms and social openness, are returning to China to start businesses. Despite Beijing’s clampdown on freedom of expression, many Chinese choose return to China (accepting with a kind of fatalism that they must access the internet through a VPN) because the economy is growing and there are, at present, great opportunities in China for the young and ambitious who are willing to work hard. The crony capitalists of Beijing will continue to thrive, along with the princelings and returned expatriates, while the rest of the world festers in China Envy, and for this reason the leadership in Beijing has a degree of impunity that other oppressive regimes can only envy.

But the Umbrella Revolution was not for nothing. If it is true that the protests in Hong Kong failed, it is equally true that “one country, two systems” has also failed — catastrophically — and that what the central government in Beijing has proved is that it can revise, abridge, or suspend any part of the Basic Law that it likes, at any time, and to any extent. In other words, the people of Hong Kong are understood to be living under the most arbitrary tyranny conceivable, and in this sense have fewer rights and freedoms than mainland Chinese. This will have consequences not only for Hong Kong and mainland China, but also for the desire of the leadership in Beijing to negotiate reunification with Taiwan (cf. China’s Long Game With Taiwan Just Got Longer by David J. Lynch).

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Right of the People to Alter or to Abolish

4 July 2014

Friday

“Writing the Declaration of Independence, 1776, by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris. Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin were named to a committee to prepare a declaration of independence. Jefferson (standing) did the actual writing because he was known as a good writer. Congress deleted Jefferson’s most extravagant rhetoric and accusations.” (Virginia Historical Society)

On this, the 238th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, I would like to recall what is perhaps the centerpiece of the document: a ringing affirmation of what would later, during the French Revolution, be called “The Rights of Man,” and how and why a people with “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind” should go about securing these rights:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.

The famous litany of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness names certain specific instances, we note, among the unalienable rights of human beings (a partial, and not an exhaustive list of such rights), and in the very same paragraph the founders have mentioned the Right of the People to alter or to abolish any form of government that becomes destructive to these ends. This is significant; the right of the people to alter or abolish a government that is destructive of unalienable rights is itself an unalienable right, though qualified by the condition that established governments should not be lightly overthrown. The Founders did not say that long established governments should never be overthrown, since they were in the process of overthrowing the government of one of the oldest kingdoms in Europe, but that such an action should not be undertaken lightly.

In keeping with with a prioristic language of self-evident truths, the Founders have formulated the right to alter or to abolish in terms of forms of government. In other words, the right to alter or abolish is framed not in terms of particular tyrannical or corrupt regimes, but on the form of the regime. This is political Platonism, pure and simple. The Founders are here recognizing that there are a few distinct forms of government, just as there are a few distinct unalienable rights. For the political Platonism of the Anglophone Enlightenment, forms of government and unalienable rights are part of the furniture of the universe (a phrase I previously employed in Defunct Ideas and some other posts).

It has always been the work of revolutions to alter or to abolish forms of government, and this is still true today, although we are much less likely to think in these platonistic terms about the forms of governments and unalienable rights. To be sure, the idea of rights has become absolutized to a certain extent in the contemporary world, but it is a conflicted absolute idea, because it is an absolute idea stranded in a society that no longer believes in absolute ideas. In just the same way, the governmental tradition of the US is a “stranded asset” of history — an anachronistic relic of the Enlightenment that has survived through several post-Enlightenment periods of history and still survives today. The language of the Enlightenment can still speak to us today — it has a perennial resonance with human nature — but if you can get a typical representative of our age to engage in a detailed conversation about political ideals, you will not find many proponents of Enlightenment ideals, such as the perfectibility of man, throwing off past superstitions, the belief in progress, the dawning of a new world, and a universalist conception of human nature. These are, now, by-and-large, defunct ideas. But not entirely.

If you do find these Enlightenment ideals, you will find them in a very different form than the form that they took among the Enlightenment Founders of the American republic — and note here my use of “form” and again the Platonism that implies. Those today who most passionately believe in the Enlightenment ideals of progress, perfectibility, and a new world on the horizon are, by and large, transhumanists and singulatarians. They believe (often enthusiastically) in an optimistic vision of a better future, although the future they envision would be, for some among us, a paradigm of moral horror — human beings altered beyond all recognition and leading lives that have little or no relationship to human lives as they have been lived since the beginning of civilization.

Transhumanists and singulatarians also believe in the right of the people to alter or to abolish institutions that have become destructive of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — but the institutions they seek to alter or abolish are none other than the institutions of the human body and the human mind (or, platonistically speaking, the form of the human body and the form of the human mind), far older than any form of government, and presumably not to be lightly altered or abolished. Looking at the contemporary literature on transhumanism, with some arguing for and some arguing against, it is obvious that one of the great moral conflicts in the coming century (and perhaps for some time after, until some settlement is reached, or until we and our civilization are so transformed that the question loses its meaning) is going to be that over transhumanism, which is, essentially, a platonistic question about what it means to be human (and the attempt to define the distinction between the human and the non-human, which I recently wrote about). For some, what it means to be human is already fixed for all time and eternity; for others, what it means to be human is not fixed, but is subject to continual change and revision, taking in the whole of human prehistory and what we were before we were human.

It is likely that the coming moral conflict over transhumanism (both the conflict and transhumanism itself have already started, but they remain at the shallow end of an exponential growth curve) will eventually make itself felt as social and political conflict. The ethico-religious conflict in Europe from the advent of the Reformation to the end of the Thirty Years’ War brought into being the political institution of the nation-state and even created the conditions for the Enlightenment, as a reaction against the religious excesses the Reformation and its consequences. Similarly, the ethico-social conflict that will follow from divisions over transhumanism (and related technological developments that will blur the distinction between the human and the non-human) may in their turn be the occasion of the emergence of revolutionary changes in social and political institutions. Retaining the right of the people to alter or abolish their institutions means remaining open to such revolutionary change.

. . . . .

Happy 4th of July!

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Remembering Revolution in a Time of Rebellion

4 July 2013

Thursday

Like 1968 and 1989, 2013 is looking a little like the original “Springtime of Nations” in 1848, when popular rebellions against entrenched power spontaneously emerged in widely divergent societies. While the energies released in these revolutionary movements proved to be too scattered to form the basis of a new political order that could replace the established political order — and far short of the ideal Novus ordo seclorum imagined by Virgil — the high political drama of such events leaves an impression that should not be denied or trivialized.

It is the historical exception that the American Revolution, the French Revolution, and the Bolshevik Revolution resulted in far-reaching political changes that shaped the future of the planet entire. The first of these, the American Revolution that we celebrate today, far from being a mere ephemeral moment like the protests of today, established a political institution that was to dominate the planet, requiring less than two centuries to grow into the sole superpower in the world. Few Revolutions can boast of such an issue, but whether we want to celebrate the prescience of the Founding Fathers in pursing the expedient of regime change through political revolution and armed struggle, or whether we see this as the opening of Pandora’s Box is another matter.

How are we to understand revolution? The best summary that I have found of the nature of revolution itself is a paragraph from Sartre’s essay, “Materialism and Revolution.” This essay dates from before Sartre became a Marxist and a Maoist apologist. Mark Poster discussed the origins of this essay in the context of the post-war French communist movement and Sartre’s troubled relations with prominent French communists:

With the unrestrained polemics against Sartre from the Communists multiplying day by day, Sartre felt called upon to defend himself and his ideas. His response came in a lecture in 1945 called “Existentialism is a Humanism,” and in an article in Les Temps Modernes of 1946 entitled “Materialism and Revolution.” In these ripostes Sartre advertised his own existentialism as a true humanism, the only suitable philosophy for a liberating politics, over against the Marxism of the French Communist Party, which was a dehumanizing materialism. He proposed naively that the CP substitute existentialism for its own diamat. It was at this point in the controversy between Marxism and existentialism that the two camps were most sharply opposed and that the Communist criticisms of Being and Nothingness were most poignant. It was also at this point that Sartre was attacked by the Trotskyists because his lecture attacked Naville. Sartre’s response to the Communists was based, in general, on a defense of his concept of radical freedom as a needed ingredient in revolutionary theory: “…the basic idea of existentialism is that even in the most crushing situations, the most difficult circumstances, man is free. Man is never powerless except when he is persuaded that he is and the responsibility of man is immense because he becomes what he decides to be.”

Mark Poster, Existential Marxism in Postwar France: From Sartre to Althusser, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1975, pp. 125-126

It is a salutary exercise to remind ourselves that the later Sartre was but a shadow of his former, younger self, when he defended freedom and had not yet capitulated to Marxism — a capitulation that itself might be characterized as a failure of freedom, since Sartre capitulated to the apparent historical inevitability of Marxism, and the belief in inevitability is a form of fatalism and an abandonment of freedom (mauvaise foi, no less). In any case, here’s what Sartre wrote about revolution when he still thought that human freedom was central to revolutionary action:

“…a revolutionary philosophy ought to set aside the materialistic myth and endeavor to show: (1) That man is unjustifiable, that his existence is contingent, in that neither he nor any Providence has produced it; (2) That, as a result of this, any collective order established by men can be transcended toward other orders; (3) That the system of values current in a society reflects the structure of that society and tends to preserve it; (4) That it can thus always be transcended toward other systems which are not yet clearly perceived since the society of which they are the expression does not yet exist — but which are adumbrated are in, in a word, invented by the very effort of the members of the society to transcend it.”

Jean-Paul Sartre, Literary and Philosophical Essays, “Materialism and Revolution,” New York: Collier Books, 1955, p. 235

There is a lot going on in this passage. Its vision of a society that continually transcends itself through revolution is an explicit negation of Comte de Maistre’s finitistic political theory, which shows both Sartre and de Maistre in their true political colors: Sartre as a revolutionary, and de Maistre as a reactionary.

This passage also formulates a social and collective expression of what in Gibbon, Sartre, and the Eurozone I called Sartre’s Principle of Inalienable Autonomy for Individuals, or, more briefly, Sartre’s Principle. I contrasted Sartre’s principle as an individualistic principle to Gibbon’s principle — namely, that no assembly of legislators can bind their successors invested with powers equal to their own — which is a collective or political principle. But now I see that I could have dispensed with Gibbon and formulated the principle both in its individualistic and collectivistic forms with reference only to Sartre.

In Gibbon, Sartre, and the Eurozone I argued that the individual principle, Sartre’s Principle, was ultimately the foundation of the freedom of societies and social wholes; in other worlds, social freedom supervenes upon individual freedom.

The nearly unique value placed upon individual liberty in the American revolution is significant here: this was a revolution that was successful because it recognized the supervenience of social liberty upon individual liberty. The French and Bolshevik revolutions gave way to terrors and atrocities because their vision was of a Rousseauian majoritarianism in which the individual was to be “forced to be free.” That didn’t turn out to well.

Many of those protesting and marching and rebelling today also believe in the possibility of society transcending itself to another order, even if they cannot precisely imagine what that order will be; these efforts are likely to be successful only in so far as they respect individual liberty as the foundation of social liberty. To the extent that this grounding of liberty in the individual is denied — indeed, in so far as it is denied in the US today by fashionable anti-individualists — these efforts will fail to bear fruit.

. . . . .

Happy 4th of July!

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

A Dream Deferred

4 June 2013

Tuesday

There is a quite well-known poem by Langston Hughes titled “Harlem.” Here it is:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.Or does it explode?

Today I was talking to a friend about the anniversary of the June 4 incident, which we Westerners refer to as the Tienanmen massacre, or some similar title. My friend is Chinese, was living in China at the time, and was part of the movement for democracy. To hear about the hopes that the Chinese people had at the time for a democratic China was quite moving, and it immediately reminded me of the Langston Hughes poem, since my friend said to me that everyone who lived through the June 4 incident had their dream destroyed.

For an entire generation of Chinese, democratic governance was and has been a dream deferred. And perhaps more than a generation: one of the consequences of the Tienanmen massacre was that the military and hard-line factions of the Chinese Communist Party consolidated and extended their control, while those elements of Chinese society who were sympathetic to the democracy protesters had their careers destroyed and lost all influence in the Chinese government — more dreams deferred. In other words, the consequences of the June 4 incident were to shift the whole of Chinese society in the direction of hardliners.

In the intervening decades Chinese society has changed dramatically, and the Communist party monopoly on power has allowed, if not encouraged, every kind of change except political change. It is the oft-observed social contract of China that you can do almost anything you like, as long as you don’t question one-party rule in the country. But this so-called “social contract” is a one-sided contract enforced by the Chinese communist party’s stranglehold on power, and it is aided and abetted by the “Princelings” who found themselves all the more firmly entrenched in power as the result of the consequences of 4 June 1989.

The segue from political and military power of the generation that accompanied Mao to power to the next generation of their children, who have exploited their connections to become rich and powerful, points to a China that has made the transition directly from communist dictatorship to crony capitalism, bypassing a democratic stage of development. There have been many articles in recent years about the high life of the upper echelons of the Chinese Communist Party, and how the Princelings — children of older, influential communist party members — have taken wealth and power for themselves. An article in Foreign Policy called this “The End of the Chinese Dream” — more dreams deferred.

In my post Crony Capitalism: Macro-Parasitism under Industrialization I speculated that crony capitalism may well be the mature form that capitalism takes in industrial-technological civilization. If, unfortunately, I am right in this, the defeat of the dream of a democratic China on 4 June 1989 may mean that China has assumed the politico-economic structure that it will maintain into the foreseeable future — more dreams deferred.

How long can a dream be deferred and still remain viable, that is to say, still retain its power to inspire? When does a dream pass from deferment to destruction?

There is a political scientist — I can’t remember who it is as I am writing this — who has divided up political movements according to when in the future they locate the ideal society (i.e., utopia). Reformists see the ideal society as in the distant future, so there is no reason to do anything radical or drastic: concentrate on incremental reforms in the present, and in the fullness of time, when we are ready for it, we will have a more just and equitable social order. The radical on the contrary, in pursuit of revolution, thinks that the ideal society is just around the corner, and if we will just do x, y, and z right now we can have the ideal society tomorrow.

Talking to my Chinese friend today, and discussing the almost millenarian expectation of a democratic China, I immediate thought of this revolutionary ideal of a new society right around the corner, since my friend said to me that they felt that a democratic China was not merely a possibility, but was so close to being a reality — almost within their grasp. I also thought of the radicalism of the French Revolution, and Wordworth’s famous evocation of this time:

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!

The dream of the French Revolution issued in the nightmare of The Terror, and of course many who opposed the protesters for democracy in China did so because this is the path of development they feared: a collapse of civil society followed by years if not decades of chaos and instability. Many former communist officials who participated in the Tienanmen crack down were quite explicit about this (which is something I wrote about in Twenty-one years since Tiananmen).

To invoke yet another western poem to describe the situation in China, Chinese democracy remains the road not taken. We will never know what China and the world would have looked like if democracy had triumphed in China in 1989. We don’t know what kind of lesson China would have given to the world: an example to follow, or a warning of what to avoid. Instead, the leaders of China gave the world a very different lesson, and a very different China.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Problem with Diachronic Extrapolation

23 March 2013

Saturday

Synchronic interaction is like the ripples of rain drops in a pond, which collide with other ripples and create new patterns.

In Synchronic and Diachronic Approaches to Civilization and Axes of Historiography I discussed the differences between synchronic and diachronic approaches to historiographical analysis (and in much greater detail in Ecological Temporality and the Axes of Historiography). The synchronic/diachronic distinction can also be useful in futurism, and in fact we can readily distinguish between what I will call synchronic extrapolation and diachronic extrapolation.

If we understand synchrony as, “the present construed broadly enough to admit of short term historical interaction” (as I formulated it in Axes of Historiography), then synchronic extrapolation is the extrapolation of a broadly construed present across its interactions. This may not sound very enlightening, but you’ll understand immediately what I mean when I relate it to chaos and complexity. Recent interest in chaos theory and what is known as the “butterfly effect” has led some to think in terms of synchronic extrapolation since the idea of the is of a small event the interactions of which cascade to produce significant consequences.

As a form of futurism, synchronic extrapolation is not familiar (probably because it doesn’t take us very far forward into the future), but we need to keep it in mind in order to contrast it with diachronic extrapolation. Diachronic extrapolation is one of the most familiar forms of futurism today, especially as embodied in Ray Kurzweil’s love of exponential growth curves, which are usually diachronic extrapolations. One of the reasons that I remain so skeptical about the claims of Kurzweil and other singulatarians (even though I have learned a lot about them recently and have a less negative picture overall than initially) is the heavy reliance on diachronic extrapolation in their futurism. I frequently cite specific examples of failed exponential growth curves or technologies (like chemical rockets) that seem to be stuck in a technological rut (what I have called a stalled technology), experiencing little or no development (and certainly not exponential development), and I do this because readers usually find specific, particular examples persuasive.

The straight line of causality of falling dominoes constitutes another model of diachronic extrapolation.

I have discovered over the course of many conversations that most people tune out extended theoretical expositions, and only sort of wake up and pay attention when you give a concrete example. So I do this, to the best of my ability. But really, the dispute with diachronic extrapolation (and particular schools of futurist thought that employ diachronic extrapolation to the exclusion of other methods, such as the singulatarians) is theoretical, and all the examples in the world aren’t going to get to the nub of the problem, which must be given the theoretical exposition that it deserves. And the nub of the problem is simply that diachrony over significant periods of time cannot be pursued in isolation, since any diachronic extrapolation will interact with changed conditions over time, and this interaction will eventually come to constitute the consequences as must as the original trend diachronically extrapolated.

Diachronic extrapolation may be derailed by historical singularities, but it is far more frequent that nothing so discontinuous as a singularity need happen in order for a straight-forward extrapolation of present trends fail to be be realized. I specifically single out diachronic extrapolation in isolation, because the most frequent form of failed futurism is to take a trend in the present and to project it into the future, but any futurism worthy of the name must understand events in both their synchronic and diachronic context; isolation from succession in time is just as invidious as isolation from interaction across time. This simultaneous synchrony and diachrony resembles a chain reaction of ever-growing consequences from the initial point of departure.

In my two immediately previous posts — Addendum on Automation and the Human Future and Bertrand Russell as Futurist — I dealt obliquely with the problems of diachronic extrapolation. Predicting technogenic unemployment on the basis of contemporary automation, or predicting a bifurcation between annihilation or world government, is a paradigm case of diachronic extrapolation that fails to sufficiently take into account future interactions that will become as important or more important than the diachronically extrapolated trend.