Cosmic War: An Eschatological Conception

14 October 2010

Thursday

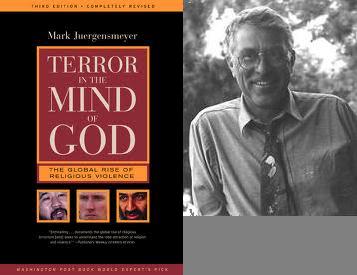

A few days ago in Politicized Anger I mentioned that I have been studying How to Win a Cosmic War: God, Globalization, and the End of the War on Terror by Reza Aslan. In the book, Aslan mentioned that he took the idea of cosmic war mentioned in the title of his book from Mark Juergensmeyer’s book, Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence, Chapter 8 of which is concerned with the idea of cosmic war. Juergensmeyer is a well-known scholar in religious studies who began his career at the Union Theological Seminary, studying to become a Methodist minister, there a student of Reinhold Niebuhr.

When I first saw Aslan’s How to Win a Cosmic War: God, Globalization, and the End of the War on Terror — for I happened upon it browsing the shelves of a library; I hadn’t read any reviews or even heard of it before I saw it — I was immediately interested and intrigued as I could see right away that a cosmic war clearly falls under the umbrella of the eschatological conception of history.

The eschatological conception of history assumes non-human agency in the world, and any human agency under this conception is mediated by non-human agency.

In several posts — Three Conceptions of History, Revolution and Human Agency, and The Naturalistic Conception of History, inter alia — I have been developing a general framework for understanding the overall conceptions that people bring to their understanding of history. This framework is based upon differing conceptions of human agency in the world. That is to say, the framework for understanding how people understand their history is based on how they understand their role in history. Are we helpless before the events of the world? Can we make of our lives anything we desire? Must we seek to supplicate unseen powers? Is human being-in-the-world no different in essentials from a tree’s being-in-the-world? A “Yes” to one of these questions places you, respectively, under the catastrophic, political, eschatological, or naturalistic conception of history.

Juergensmeyer in his above-mentioned book discusses several contemporary examples of religiously-inspired terrorism and war, saying that the religious militants have been “driven by an image of cosmic war.” He goes on to say:

“I call such images ‘cosmic’ because they are larger than life. They evoke great battles of the legendary past, and they relate to metaphysical conflicts between good and evil. Notions of cosmic war are intimately personal but can also be translated to the social plane. Ultimately, though, they transcend human experience. What makes religious violence particularly savage and relentless is that its perpetrators have placed such religious images of divine struggle — cosmic war — in the service of worldly political battles. For this reason, acts of religious terror serve not only as tactics in a political strategy but also as evocations of a much larger spiritual confrontation.”

Mark Juergensmeyer, Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence, Chapter 8, pp. 149-150

Aslan in his book follows Juergensmeyer closely in these formulations. Aslan says of the 11 September hijackers:

“They were engaged in a metaphysical conflict, not between armies or nations but between the angels of light and the demons of darkness. They were fighting a cosmic war, not against the American imperium but against the eternal forces of evil. A cosmic war is a religious war. It is a conflict in which God is believed to be directly engaged on one side over the other. Unlike a holy war — an earthly battle between rival religious groups — a cosmic war is like a ritual drama in which participants act out on earth a battle they believe is actually taking place in the heavens.”

Reza Aslan, How to Win a Cosmic War: God, Globalization, and the End of the War on Terror, Introduction, p. 5

I find this very interesting, but I would like to see it developed with much greater care and rigor. Both Juergensmeyer and Aslan are rather cavalier in their language. I heartily approve of Aslan’s careful distinction between holy war and cosmic war, but I would also suggest that in the interests of analytical clarity we should also distinguish cosmic war and metaphysical war, with the latter as the broader category, while the former is a particular kind of metaphysical conflict, and especially a supernatural kind of metaphysical conflict. This is important, as one could characterize the crusading spirit of early twentieth century communism (or even the French Revolution earlier) as exemplifying a metaphysical conflict of an explicitly materialistic (perhaps naturalistic) metaphysic.

I would myself prefer to speak in terms of eschatological war as being an expression of the eschatological conception of history, but it is just as well with me to speak in terms of cosmic war. The point I want to make in this connection is that the idea of cosmic war does not exist in an intellectual vacuum. It is part of a way of seeing and understanding the world; it is part of a Weltanschauung. This is relevant to some of Aslan’s claims.

Twice in his book, near the beginning and near the end, Aslan writes that the only way to win a cosmic war is to refuse to fight one. We are to decline eschatological combat. Aslan is right when we says that cosmic wars are unwinnable, and therefore also unlosable (p. 8). But Aslan also claims that aggrieved communities have legitimate grievances, and that these need to be addressed. I agree with this, but I also know from my reading of history the near hopelessness of this task. What task? The attempt to “help” people in utilitarian and pragmatic ways when their grievances are not expressed in utilitarian and pragmatic terms. Many efforts of the US around the world have come to grief on this rock.

Because a cosmic war does not occur in a cosmic vacuum, but it occurs in an overall conception of the world, the grievances too occur within this overall conception of history. If we attempt to ameliorate grievances formulated in an eschatological context with utilitarian and pragmatic means, no matter what we do it will never be enough, and never be right. An eschatological solution is wanted to grievances understood eschatologically, and that is why, in at least some cases, religious militants turn to the idea of cosmic war. Only a cosmic war can truly address cosmic grievances.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

I’d like to make notice of something troubling

I’ve noticed since the Syria civil war started

that a lot of pro-gov Syrian polticians started using the word

“Cosmic conspiracy against Syria”

while some of Iran politician are using eschatological events to push for a confrontation against their opponents in the ME

while its not the monopoly of Middle easterns ( The christian Zionists use that too to defend Israel at all costs)

Thanks for your comment!

Just today on my other blog I wrote about the growing popularity of the cult of Santa Muerte in Latin America, which is another contemporary instance of belief in the intercession of cosmic powers into mundane events.

These recent and ongoing examples demonstrate that the eschatological conception of history is alive and well in the twenty-first century, despite the steady pressure that industrial-technological civilization has put on traditional religious beliefs. Some of this can be put down to an attempt to cynically manipulate the simple and the gullible, but this obviously begs the question, since such techniques of manipulation would not be successful if the eschatological conception of history were not still prevalent.

From a meta-historical perspective, the really interesting question here is whether more mischief is caused as a result of illegitimately invoking the eschatological conception of history as balanced against the hope and comfort that it gives to many people in distress.

In any case, the continuing prevalence of the eschatological conception of history demonstrates to us that cosmic responses to cosmically-posed questions are still required, since I have pointed out in my analyses of the eschatological conception of history that a problem that is posed eschatologically will be be regarded as addressed until it has been addressed in the same spirit in which it is invoked.

Best wishes,

Nick

In the Syrian case I suspect its more the supernatural Conspiracy kind

mundane conspiracies exists but the belief of a supernatural evil order conspiring and blaming all events on it is the thing the conspiraloons do and in the Syrian case it applies

as of the eschatological belief like you have proposed it may be a self fulfilling prophecy or a grander order that history researchers have yet to discover (Assimov’s fictional psychohistory)