Reconstructing Biosphere Evolution

17 August 2016

Wednesday

In Rational Reconstructions of Time I noted that stellar evolution takes place on a scale of time many orders of magnitude greater than the human scale of time, but that we are able to reconstruct stellar evolution by looking into the cosmos and, among the billions of stars we can see, picking out examples of stars in various stages of their evolution and sequencing these stages in a kind of astrophysical seriation. Similarly, the geology of Earth takes place on a scale of time many orders of magnitude removed from human scales of time, but we have been able to reconstruct the history of our planet through a careful study of those traces of evidence not wiped away by subsequent geological processes. Moreover, our growing knowledge of exoplanetary systems is providing a context in which the geological history of Earth can be understood. We are a long way from understanding planet formation and development, but we know much more than we did prior to exoplanet discoveries.

The evolution of a biosphere, like the evolution of stars, takes place at a scale of time many orders of magnitude beyond the human scale of time, and, as with stellar evolution, it is only relatively recently that human beings have been able to reconstruct the history of the biosphere of their homeworld. This began with the emergence of scientific geology in the eighteenth century with the work of James Hutton, and accelerated considerably with the nineteenth century work of Charles Lyell. Scientific paleontology, starting with Cuvier, also contributed significantly to understanding the natural history of the biosphere. A more detailed understanding of biosphere evolution has begun to emerge with the systematic application of the methods of scientific historiography. The use of varve chronology for dating annual glacial deposits, dendrochronology, and the Blytt–Sernander system for dating the layers in peat bogs, date to the late nineteenth century; carbon-14 dating, and other methods based on nuclear science, date to the middle of the twentieth century. The study of ice cores from Antarctica has proved to be especially valuable in reconstruction past climatology and atmosphere composition.

The only way to understand biospheric evolution is through the reconstruction of that evolution on the basis of evidence available to us in the present. This includes the reconstruction of past geology, climatology, oceanography, etc. — all Earth “systems,” as it were — which, together with life, constitute the biosphere. We have been able to reconstruct the history of life on Earth not from fossils alone, but from the structure of our genome, which carries within itself a history. This genetic historiography has pushed back the history of the origins of life through molecular phylogeny to the very earliest living organisms on Earth. For example, in July 2016 Nature Microbiology published “The physiology and habitat of the last universal common ancestor” by Madeline C. Weiss, Filipa L. Sousa, Natalia Mrnjavac, Sinje Neukirchen, Mayo Roettger, Shijulal Nelson-Sathi, and William F. Martin (cf. the popular exposition “LUCA, the Ancestor of All Life on Earth: A new genetic analysis points to hydrothermal vents as the planet’s first habitat” by Dirk Schulze-Makuch; also We’ve been wrong about the origins of life for 90 years by Arunas L. Radzvilavicius) showing that recent work in molecular phylogeny points to ocean floor hydrothermal vents as the likely point of origin for life on Earth.

This earliest history of life on Earth — that terrestrial life that is the most different from life as we know it today — is of great interest to us in reconstructing the history of the biosphere. If life began on Earth from a single hydrothermal vent at the bottom of an ocean, life would have spread outward from that point, the biosphere spreading and also thickening as it worked its way down in the lithosphere and as it eventually floated free in the atmosphere. If, on the other hand, life originated in an Oparin ocean, or on the surface of the land, or in something like Darwin’s “warm little pond” (an idea which might be extended to tidepools and shallows), the process by which the biosphere spread to assume its present form of “planetary scale life” (a phrase employed by David Grinspoon) would be different in each case. If the evolution of planetary scale life is indeed different in each case, it is entirely possible that life on Earth is an outlier not because it is the only life in the universe (the rare Earth hypothesis), but because life of Earth may have arisen by a distinct process, or attained planetary scale by a distinct mechanism, not to be found among other living worlds in the cosmos. We simply do not know at present.

Once life originated at some particular point on Earth’s surface, or deep in the oceans, and it expanded to become planetary scale life, there seems to have been a period of time when life consisted primarily of horizontal gene transfer (a synchronic mechanism of life, as it were), before the mechanisms of species individuation with vertical gene transfer and descent with modification (a diachronic mechanism of life). It is now thought the the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) will only be able to be traced back to this moment of transition in the history of life, but this is an area of active research, and we simply do not yet know how it will play out. But if we could visit many different worlds in the earliest stages of the formation of their respective biospheres, we would be able to track this transition, which may occur differently in different biospheres. Or it may not occur at all, and a given biosphere might remain at the level of microbial life, experiencing little or no further development of emergent complexity, until it ceased to be habitable.

While we can be confident that later emergent complexities must wait for earlier emergent complexities to emerge first, no other biosphere is going to experience the same stages of development as Earth’s biosphere, because the development of the biosphere is a function of a confluence of contingent circumstances. The history of a biosphere is the unique fingerprint of life upon its homeworld. Any other planet will have different gravity, different albedo, different axial tilt, axial precession, orbital eccentricity, and orbital precession, and I have explained elsewhere how these cycles function as speciation pumps. The history of life on Earth has also been shaped by catastrophic events like extraterrestrial impacts and episodes of supervolcano eruptions. It was for reasons such as this that Stephen J. Gould said that life on Earth as we know it is, “…the result of a series of highly contingent events that would not happen again if we could rewind the tape.”

Understanding Earth’s biosphere — the particularities of its origins and the sequence of its development — is only the tip of the iceberg of reconstructing biospheres. Ultimately we will need to understand Earth’s biosphere in the context of any possible biosphere, and to do this we will need to understand the different possibilities for the origins of life and for possible sequences of development. There may be several classes of world constituted exclusively with life in the form of microbial mats. Suggestive of this, Abel Mendez wrote on Twitter, “A habitable planet for microbial life is not necessarily habitable too for complex life such as plants and animals.” I responded to this with, “Eventually we will have a taxonomy of biospheres that will distinguish exclusively microbial worlds from others…” And our taxonomy of biospheres will have to go far beyond this, mapping out typical sequences of development from the origins of life to the emergence of intelligence and civilization, when life begins to take control of its own destiny. On our planet, we call this transition the Anthropocene, but we can see from placing the idea in this astrobiological context that the Anthropocene is a kind of threshold event that could have its parallel in any biosphere productive of an intelligent species that becomes the progenitor of a civilization. Thus planetary scale life is, in the case of the Anthropocene, followed by planetary scale intelligence and planetary scale civilization.

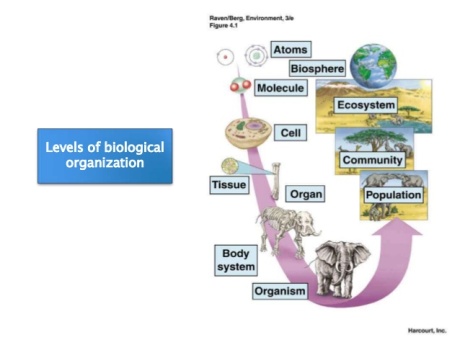

Ultimately, our taxonomy of the biosphere must transcend the biosphere and consider circumstellar habitable zones (CHZ) and galactic habitable zones (GHZ). In present biological thought, the biosphere is the top level of biological organization; in astrobiological thought, we must become accustomed to yet higher levels of biological organization. We do not yet know if there has been an exchange of life between the bodies of our planetary system (this has been posited, but not yet proved), in the form of lithopanspermia, but whether or not it is instantiated here, it is likely instantiated in some planetary system somewhere in the cosmos, and in such planetary systems the top level of biological organization will be interplanetary. We can go beyond this as well, positing the possibility of an interstellar level of biological organization, whether by lithopanspermia or by some other mechanism (which could include the technological mechanism of a spacefaring civilization; starships may prove to be the ultimate sweepstakes dispersion vector). Given the possibility of multiple distinct interplanetary and interstellar levels of biological organization, we may be able to formulate taxonomies of CHZs for various planetary systems and GHZs for various galaxies.

One can imagine some future interstellar probe that, upon arrival at a planetary system, or at a planet known to possess a biosphere (something we would know long before we arrived), would immediately gather as many microorganisms as possible, perhaps simply by sampling the atmosphere or oceans, and then run the genetic code of these organisms through an onboard supercomputer, and, within hours, or at most days, of arrival, much of the history of the biosphere of that planet would be known through molecular phylogeny. A full understanding of the biospheric evolution (or CHZ evolution) would have to await coring samples from the lithosphere and cryosphere of the planet or planets, and, but the time we have the technology to organize such an endeavor, this may be possible as well. At an ever further future reach of technology, an intergalactic probe arriving at another galaxy might disperse further probes to scatter throughout the galaxy in order to determine if there is any galactic level biological organization.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .