The Franchise Problem

13 December 2017

Wednesday

Is an inclusive franchise a bug or a feature of democracy?

One of the unquestioned political values (if not ideals) of our time is not only that of liberal democracy, but, even more-so, liberal democracy with the broadest possible franchise. Many today regard the expansion of the franchise as one of the most important accomplishments of contemporary civil society and civil rights. Indeed, the limited franchise of democracies prior to the twentieth century expansion of the voting franchise is today regarded as a terrible moral stain on earlier societies. But what if a limited franchise were not a bug but rather a feature of early democracies? Can democracy even function with a universal franchise? We don’t know. Political societies in their contemporary form of a nearly universal franchise are historically very young, and we cannot yet say whether or not these political experiments will be successful.

Even to suggest a restriction on the franchise after a century of expansion is political heresy in the western world, but we may be forced into accepting some limitation on voting rights in order to salvage our societies, which seem bent on self-destruction. It is likely that the most we can do at this point in the history of western civilization is to salvage what can be salvaged from the Enlightenment project; more radically, western civilization may need to sever its relationship to the Enlightenment project and adopt some other ideological formation as its central project, and this would likely be a process as fraught as the Thirty Years’ War, which was one of the causes of the formation of the Enlightenment project. I think it would be preferable to experiment with different implementations of the Enlightenment project though different franchise regimes, when seen in comparison to the chaos that would ensue from entirely dispensing with the Enlightenment project. Thus, I am well aware that the present discussion lies outside the configuration of the Overton window as it functions in contemporary western societies, but I think that this discussion can be conducted in a rational way, and that it may suggest political experiments that have never yet been tried in the history of humanity.

Even before the age of the nearly universal franchise, democracy was believed to be unworkable. Plato and Aristotle had nothing good to say about democracy — after all, it had been democratic Athens that had condemned Socrates to death. In modern times there is a well-known quote from Alexander Fraser Tytler, often mis-attributed to Alexis de Tocqueville, suggesting that democracy is fatally flawed:

“A Democracy cannot exist as a permanent form of government. It can only exist until the voters discover they can vote themselves largess out of the public treasury. From that moment on the majority always votes for the candidate promising the most benefits from the public treasury with the results that Democracy always collapses over a loose fiscal policy, always to be followed by a dictatorship.”

While this was written before the nearly universal franchise of contemporary democracies, it points to a structural problem in democracies that is only made worse by the expanding scope of the franchise. The practical consequence of a nearly universal franchise is that voting rights have been given to an even greater number individuals who are not stakeholders in society except in so far as their “stake” in society is the value that they extract from the others in that society that produce value. Very few individuals are productive members of society — most consume more than they contribute to the common weal. It sounds cruel to say it, but this is a case in which we must eventually be cruel to be kind. The dependent members of a society will suffer more in the long run from the collapse of that society than they would suffer from being excluded from the franchise.

A democracy with a limited franchise has as its goal a franchise that is restricted to productive stakeholders in society. Limiting the vote to property owners was one way to accomplish this, and moreover this retained a connection to the feudal past, in which the lords of feudal estates were a law unto themselves in the decentralized power structure of feudalism. Nevertheless, democracy has deep roots in western society, and many of these feudal societies had democratic aspects that we fail to recognize as democratic today because of the severely restricted franchise. For example, when the aldermen of a town gathered to make a decision, this was an essentially democratic institution. Many such institutions existed on a local level, and they reached up all the way to the election of the Holy Roman Emperor, where the franchise was limited to prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire electoral college. The Vatican retains a system like this to the present day, in which the College of Cardinals elects the Pope, not a mass ballot among Roman Catholics.

In past democratic societies, voting rights were restricted across categories of age, sex, and race, and these are precisely the categories that became the focus of identity politics in our own time. Since these past categories of franchise limitation have proved to be so divisive, the obvious political experiment is to attempt franchise limitations based on other categories (though it is easy to predict that any condition placed on voting would rapidly become stigmatized as a method employed by the powerful to shut out powerless sectors of society from ever gaining political power). Above the idea of limiting the franchise to property owners has been noted. Another idea that regularly recurs, and which is found in Heinlein’s Starship Troopers, is the limitation of the franchise to veterans. It would also be possible to limit the franchise to net taxpayers (those who pay more taxes to the government than the value they derive in government services, though this calculation would of course be controversial).

A thought experiment that may help us to think our way through the franchise problem is to consider the remaining restrictions on the expansion of the franchise. Most nation-states that hold elections have a minimum age limit for voting, and most restrict voting rights to citizens. What would it be like to remove these remaining restrictions on voting rights? What would a truly universal franchise be like? Suppose anyone from anywhere in the world could come to your nation-state and vote in your election, and further suppose that children of any age could vote. This would obviously run into serious problems. A toddler could not meaningfully vote, but a toddler’s parents could take a toddler into a voting booth and record the child’s vote.

The problem of children voting points to two very interesting questions:

1) If beings who cannot meaningfully vote were included in a universal franchise, why should we limit the franchise to human beings? A dog may not be able to meaningfully vote in an election (or stand for office), but a dog’s owner could register a dog’s vote, just as a parent could register a child’s vote before that child became old enough to resist having their vote taken by their parent. If this is a problem, why exactly is it a problem? Presumably it is a problem because kennel owners would breed themselves into a position of power in society, and we think this is more likely than parents producing so many children as to capture the vote in an election. However, a very rich individual could adopt a large number of children and thereby control a disproportionate voting bloc. Is this a bad thing? If there were requirements to assure the well being of the children (as there are), this could be to the benefit of orphans. However, if children were relevant to voting, there would be far fewer orphans because children would be more politically valuable than they are today.

2) If the votes of very young children would necessarily be mediated by their parents, the child’s vote could simply be legally conferred upon the parent or guardian until that child reaches a certain age. This points to possible alternatives to contemporary franchise conventions: an individual (or a couple) could have as many votes as they have dependent children, for example. This could be administered in many different ways. Each adult might have a vote, and then one parent (or both) might have an additional number of votes corresponding to their number of dependent children. In a more radically natalist regime, the only votes could be the votes that parents exercise on behalf of their dependent children, and no adult automatically has a vote simply in virtue of being an adult. Individuals would have an opportunity to vote only when they could prove themselves to be a parent presently caring for a dependent child, which would achieve the end of having the only voters being those who are stakeholders in the future of the society in question. Additionally, this would incentivize child-rearing at a time of declining fertility rates. (Full disclosure: I have no children, so I would not be eligible to vote under such a franchise regime.)

I do not think it is likely that any contemporary political regime would adopt any of the franchise experiments suggested above in regard to parents exercising a vote on behalf on their children, but it is an interesting idea, and it points to other political experiments that could be made.

A political entity might actively manage the scope of its franchise throughout its history, changing voter qualifications as conditions change, and circumstances appear to warrant a different composition of the electorate. For example, if the age distribution of a society becomes too weighted toward the elderly, as is projected to occur in most if not all industrialized nation-states in the near future, a nation-state may choose to implement not only a lower age limit to voting, but also an upper age limit for voting. An active management of the franchise might be continual changes in both lower and upper age limits to voting eligibility.

Given the generous supply of political data, it would not be difficult for data scientists to comb through well-documented elections and to determine, ex post facto, what the result of a given election would have been if the franchise regime had been altered. If general rules could be derived from this kind of research, an analysis of the contemporary political landscape would determine the ideal composition of the electorate required to obtain a certain result. However, this meta-electoral process would itself be undemocratic. Some managerial body (or some individual) would have to determine the desired result and, on the basis of the desired result, then stipulate the constitution of the electorate, and it is difficult to imagine how such a regime could come about under contemporary social conditions.

The important exception to the above observation on the difficulty of managing an electorate under contemporary conditions is the European Union, which has de facto pursued a course like this. The political elites have made a determination of the desired end, and votes are held until the desired result is achieved. While it could be argued that this procedure has produced an unprecedented unification of Europe, it has also produced a backlash, most obviously manifested by the Brexit vote for Britain to leave the EU. The political class of Britain is staunchly opposed to this, and seem to be going about Brexit negotiations in a disingenuous fashion, while the “Remainers” continue to agitate for another vote, on the hope that this will reverse the first vote, and then we would have a return to EU business as usual, when votes are simply held until the desired result is obtained. This system does not involve tailoring the electorate in order to achieve the desired result; instead, the wording of the measures to be decided (clear or confusing as necessitated by circumstance), the date selected for the vote (convenient or inconvenient), the campaign for the vote, and threats of disaster should the vote not go according to plan, have been the methods employed to shape a putatively democratic society along non-democratic lines.

The reader may interpret the above remarks as hostile to the European Union, but while I find aspects of the European Union to be problematic, I admire the Europeans for having undertaken their grand political experiment in the constitution of a European superstate at a time when few nation-states are willing to experiment politically. The Europeans are using the tools they have at their disposal in order to attempt a reform of liberal democracy. Though this experiment is imperfect, as are all political experiments, there is much that we can learn from it. It is this spirit of political experimentation that he needed to order to test alternative voting franchise regimes such as those suggested above, and to prevent a society from becoming so politically stagnant that change becomes inconceivable.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Three Revolutions

12 November 2017

Sunday

Three Revolutions that Shaped the Modern World

The world as we know it today, civilization as we know it today (because, for us, civilization is the world, our world, the world we have constructed for ourselves), is the result of three revolutions. What was civilization like before these revolutions? Humanity began with the development of an agricultural or pastoral economy subsequently given ritual expression in a religious central project that defined independently emergent civilizations. Though widely scattered across the planet, these early agricultural civilizations had important features in common, with most of the pristine civilizations beginning to emerge shortly after the Holocene warming period of the current Quaternary glaciation.

Although independently originating, these early civilizations had much in common — arguably, each had more in common with the others emergent about the same time than they have in common with contemporary industrialized civilization. How, then, did this very different industrialized civilization emerge from its agricultural civilization precursors? This was the function of the three revolutions: to revolutionize the conceptual framework, the political framework, and the economic framework from its previous traditional form into a changed modern form.

The institutions bequeathed to us by our agricultural past (the era of exclusively biocentric civilization) were either utterly destroyed and replaced with de novo institutions, or traditional institutions were transformed beyond recognition to serve the needs of a changed human world. There are, of course, subtle survivals from the ten thousand years of agricultural civilization, and historians love to point out some of the quirky traditions we continue to follow, though they make no sense in a modern context. But this is peripheral to the bulk of contemporary civilization, which is organized by the institutions changed or created by the three revolutions.

The Scientific Revolution

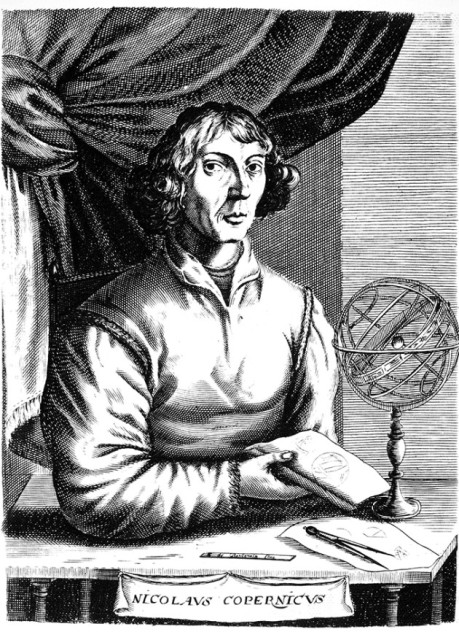

The scientific revolution begins as the earliest of the three revolutions, in the early modern period, and more specifically with Copernicus in the sixteenth century. The work of Copernicus was elaborated and built upon by Kepler, Galileo, Huygens, and a growing number of scientists in western Europe, who began with physics, astronomy, and cosmology, but, in framing a scientific method applicable to the pursuit of knowledge in any field of inquiry, created an epistemic tool that would be universally applied.

The application of the scientific method had the de facto consequence of stigmatizing pre-modern knowledge as superstition, and the attitude emerged that it was necessary to extirpate the superstitions of the past in order to build anew on solid foundations of the new epistemic order of science. This was perceived as an attack on traditional institutions, especially traditional cultural and social institutions. It was this process of the clearing away of old knowledge, dismissed as irrational superstition, and replacing it with new scientific knowledge, that gave us the conflict between science and religion that still simmers in contemporary civilization.

The scientific revolution is ongoing, and continues to revolutionize our conceptual framework. For example, four hundred years into the scientific revolution, in the twentieth century, the Earth sciences were revolutionized by plate tectonics and geomorphology, while cosmology was revolutionized by general relativity and physics was revolutionized by quantum theory. The world we understood at the end of the twentieth century was a radically different place from the world we understood at the beginning of the twentieth century. This is due to the iterative character of the scientific method, which we can continue to apply not only to bodies of knowledge not yet transformed by the scientific method, but also to earlier bodies of scientific knowledge that, while revolutionary in their time, were not fully comprehensive in their conception and formulation. Einstein recognized this character of scientific thought when he wrote that, “There could be no fairer destiny for any physical theory than that it should point the way to a more comprehensive theory, in which it lives on as a limiting case.”

Democracy in its modern form dates from 1776 and is therefore a comparatively young historical institution.

The Political Revolutions

The political revolutions that began in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, beginning with the American Revolution in 1776, followed by the French Revolution in 1789, and then a series of revolutions across South America that displaced Spain and the Spanish Empire from the continent and the western hemisphere (in a kind of revolutionary contagion), ushered in an age of representative government and popular sovereignty that remains the dominant paradigm of political organization today. The consequences of these political revolutions have been raised to the status of a dogma, so that it no longer considered socially acceptable to propose forms of government not based upon representative institutions and popular sovereignty, however dismally or frequently these institutions disappoint.

We are all aware of the experiment with democracy in classical antiquity in Athens, and spread (sometimes by force) by the Delian League under Athenian leadership until the defeat of Athens by the Spartans and their allies. The ancient experiment with democracy ended with the Peloponnesian War, but there were quasi-democratic institutions throughout the history of western civilization that fell short of perfectly representative institutions, and which especially fell short of the ideal of popular sovereignty implemented as universal franchise. Aristotle, after the Peloponnesian War, had already converged on the idea of a mixed constitution (a constitution neither purely aristocratic nor purely democratic) and the Roman political system over time incorporated institutions of popular participation, such as the Tribune of the People (Tribunus plebis).

Medieval Europe, which Kenneth Clark once called a, “conveniently loose political organization,” frequently involved self-determination through the devolution of political institutions to local control, which meant that free cities might be run in an essentially democratic way, even if there were no elections in the contemporary sense. Also, medieval Europe dispensed with slavery, which had been nearly universal in the ancient world, and in so doing was responsible for one of the great moral revolutions of human civilization.

The political revolutions that broke over Europe and the Americas with such force starting in the late eighteenth century, then, had had the way prepared for them by literally thousands of years of western political philosophy, which frequently formulated social ideals long before there was any possibility of putting them into practice. Like the scientific revolution, the political revolutions had deep roots in history, so that we should rightly see them as the inflection points of processes long operating in history, but almost imperceptible in their earliest expression.

Early industrialization often had an incongruous if not surreal character, as in this painting of traditional houses silhouetted again the Madeley Wood Furnaces at Coalbrookdale.

The Industrial Revolution

The industrial revolution began in England with the invention of James Watt’s steam engine, which was, in turn, an improvement upon the Newcomen atmospheric engine, which in turn built upon a long history of an improving industrial technology and industrial infrastructure such as was recorded in Adam Smith’s famous example of a pin factory, and which might be traced back in time to the British Agricultural Revolution, if not before. The industrial revolution rapidly crossed the English channel and was as successful in transforming the continent as it had transformed England. The Germans especially understood that it was the scientific method as applied to industry that drove the industrial revolution forward, as it still does today. It is science rather than the steam engine that truly drove the industrial revolution.

As the scientific revolution drove epistemic reorganization and the political revolutions drove sociopolitical reorganization, the industrial revolution drove economic reorganization. Today, we are all living with the consequences of that reorganization, with more human beings than ever before (both in terms of absolute numbers and in terms of rates) living in cities, earning a living through employment (whether compensated by wages or salary is indifferent; the invariant today is that of being an employee), and organizing our personal time on the basis of clock times that have little to do with the sun and the moon, and schedules that have little or no relationship to the agricultural calendar.

The emergence of these institutions that facilitated the concentration of labor (what Marx would have called “industrial armies”) where it was most needed for economic development indirectly meant the dissolution of multi-generational households, the dissolution of the feeling of being rooted in a particular landscape, the dissolution of the feeling of belonging to a local community, and the dissolution of the way of life that was embodied in these local communities of multi-generational households, bound to the soil and the climate and the particular mix of cultivars that were dietary staples. As science dismissed traditional beliefs as superstition, the industrial revolution dismissed traditional ways of life as impractical and even as unhealthy. Le Courbusier, a great prophet of the industrial city, possessed of revolutionary zeal, forcefully rejected pre-modern technologies of living, asserting, “We must fight against the old-world house, which made a bad use of space. We must look upon the house as a machine for living in or as a tool.”

Revolutionary Permutations

Terrestrial civilization as we know it today is the product of these three revolutions, but must these three revolutions occur, and must they occur in this specific order, for any civilization whatever that would constitute a peer technological civilization with which we might hope to engage in communication? That is to say, if there are other civilizations in the universe (or even in a counterfactual alternative history for terrestrial civilization), would they have to arrive at radio telescopes and spacecraft by this same sequence of revolutions in the same order, or would some other sequence (or some other revolutions) be equally productive of technological civilizations?

This may well sound like a strange question, perhaps an arbitrary question, but this is the sort of question that formal historiography asks. In several posts I have started to outline a conception of formal historiography in which our interest is not only in what has happened on Earth, or what might yet happen on Earth, but what can happen with any civilization whatsoever, whether on Earth or elsewhere (cf. Big History and Scientific Historiography, History in an Extended Sense, Rational Reconstructions of Time, An Alternative Formulation of Rational Reconstructions of Time, and Placeholders for Null-Valued Time). While this conception is not formulated for the express purpose of investigating questions like the Fermi paradox, I hope that the reader can see how such an investigation bears upon the Fermi paradox, the Drake equation, and other “big picture” conceptions that force us to think not in terms of terrestrial civilization, but rather in terms of any civilization whatever.

From a purely formal conception of social institutions, it could be argued that something like these revolutions would have to take place in something like the terrestrial order. The epistemic reorganization of society made it possible to think scientifically about politics, and thus to examine traditional political institutions rationally in a spirit of inquiry characteristic of the Enlightenment. Even if these early forays into political science fall short of contemporary standards of rigor in political science, traditional ideas like the divine right of kings appeared transparently as little better than political superstitions and were dismissed as such. The social reorganization following from the rational examination the political institutions utterly transformed the context in which industrial innovations occurred. If the steam engine or the power loom had been introduced in a time of rigid feudal institutions, no one would have known what to do with them. Consumer goods were not a function of production or general prosperity (as today), but rather were controlled by sumptuary laws, much as the right to engage in certain forms of commerce was granted as a royal favor. These feudal political institutions would not likely have presided over an industrial revolution, but once these institutions were either reformed or eliminated, the seeds of the industrial revolution could take root.

In this interpretation, the epistemic reorganization of the scientific revolution, the social reorganization of the political revolutions, and the economic reorganization of the industrial revolution are all tightly-coupled both synchronically (in terms of the structure of society) and diachronically (in terms of the historical succession of this sequence of events). I am, however, suspicious of this argument because of its implicit anthropocentrism as well as its teleological character. Rather than seeking to justify or to confirm the world we know, framing the historical problem in this formal way gives us a method for seeking variations on the theme of civilization as we know it; alternative sequences could be the basis of thought experiments that would point to different kinds of civilization. Even if we don’t insist that this sequence of revolutions is necessary in order to develop a technological civilization, we can see how each development fed into subsequent developments, acting as a social equivalent of directional selection. If the sequence were different, presumably the directional selection would be different, and the development of civilization taken in a different direction.

I will not here attempt a detailed analysis of the permutations of sequences laid out in the graphic above, though the reader may wish to think through some of the implications of civilizations differently structured by different revolutions at different times in their respective development. For example, many science fiction stories imagine technological civilizations with feudal institutions, whether these feudal institutions are retained unchanged from a distant agricultural past, or whether they were restored after some kind of political revolution analogous to those of terrestrial history, so one could say that, prima facie, political revolution might be entirely left out, i.e., that political reorganization is dispensable in the development of technological civilization. I would not myself make this argument, but I can see that the argument can be made. Such arguments could be the basis of thought experiments that would present civilization-as-we-do-not-know-it, but which nevertheless inhabit the same parameter space of civilization-as-we-know-it.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

A Dream Deferred

4 June 2013

Tuesday

There is a quite well-known poem by Langston Hughes titled “Harlem.” Here it is:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.Or does it explode?

Today I was talking to a friend about the anniversary of the June 4 incident, which we Westerners refer to as the Tienanmen massacre, or some similar title. My friend is Chinese, was living in China at the time, and was part of the movement for democracy. To hear about the hopes that the Chinese people had at the time for a democratic China was quite moving, and it immediately reminded me of the Langston Hughes poem, since my friend said to me that everyone who lived through the June 4 incident had their dream destroyed.

For an entire generation of Chinese, democratic governance was and has been a dream deferred. And perhaps more than a generation: one of the consequences of the Tienanmen massacre was that the military and hard-line factions of the Chinese Communist Party consolidated and extended their control, while those elements of Chinese society who were sympathetic to the democracy protesters had their careers destroyed and lost all influence in the Chinese government — more dreams deferred. In other words, the consequences of the June 4 incident were to shift the whole of Chinese society in the direction of hardliners.

In the intervening decades Chinese society has changed dramatically, and the Communist party monopoly on power has allowed, if not encouraged, every kind of change except political change. It is the oft-observed social contract of China that you can do almost anything you like, as long as you don’t question one-party rule in the country. But this so-called “social contract” is a one-sided contract enforced by the Chinese communist party’s stranglehold on power, and it is aided and abetted by the “Princelings” who found themselves all the more firmly entrenched in power as the result of the consequences of 4 June 1989.

The segue from political and military power of the generation that accompanied Mao to power to the next generation of their children, who have exploited their connections to become rich and powerful, points to a China that has made the transition directly from communist dictatorship to crony capitalism, bypassing a democratic stage of development. There have been many articles in recent years about the high life of the upper echelons of the Chinese Communist Party, and how the Princelings — children of older, influential communist party members — have taken wealth and power for themselves. An article in Foreign Policy called this “The End of the Chinese Dream” — more dreams deferred.

In my post Crony Capitalism: Macro-Parasitism under Industrialization I speculated that crony capitalism may well be the mature form that capitalism takes in industrial-technological civilization. If, unfortunately, I am right in this, the defeat of the dream of a democratic China on 4 June 1989 may mean that China has assumed the politico-economic structure that it will maintain into the foreseeable future — more dreams deferred.

How long can a dream be deferred and still remain viable, that is to say, still retain its power to inspire? When does a dream pass from deferment to destruction?

There is a political scientist — I can’t remember who it is as I am writing this — who has divided up political movements according to when in the future they locate the ideal society (i.e., utopia). Reformists see the ideal society as in the distant future, so there is no reason to do anything radical or drastic: concentrate on incremental reforms in the present, and in the fullness of time, when we are ready for it, we will have a more just and equitable social order. The radical on the contrary, in pursuit of revolution, thinks that the ideal society is just around the corner, and if we will just do x, y, and z right now we can have the ideal society tomorrow.

Talking to my Chinese friend today, and discussing the almost millenarian expectation of a democratic China, I immediate thought of this revolutionary ideal of a new society right around the corner, since my friend said to me that they felt that a democratic China was not merely a possibility, but was so close to being a reality — almost within their grasp. I also thought of the radicalism of the French Revolution, and Wordworth’s famous evocation of this time:

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!

The dream of the French Revolution issued in the nightmare of The Terror, and of course many who opposed the protesters for democracy in China did so because this is the path of development they feared: a collapse of civil society followed by years if not decades of chaos and instability. Many former communist officials who participated in the Tienanmen crack down were quite explicit about this (which is something I wrote about in Twenty-one years since Tiananmen).

To invoke yet another western poem to describe the situation in China, Chinese democracy remains the road not taken. We will never know what China and the world would have looked like if democracy had triumphed in China in 1989. We don’t know what kind of lesson China would have given to the world: an example to follow, or a warning of what to avoid. Instead, the leaders of China gave the world a very different lesson, and a very different China.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Ica to Lima

24 January 2012

Tuesday

Even a brief look at Peru reveals a society, which though burdened by a great disparity of rich and poor as is commonplace throughout Latin America, nevertheless shows clear signs of increasingly distributed prosperity — it would not be going too far to call this process of increasingly distributed prosperity economic democratization.

The day's drive began at the wonderful El Carmelo Hotel and Hacienda in Ica, a former pisco distillery.

The highways in Peru are my Exhibit “A” for economic democratization — the roads themselves are well maintained and well traveled, but more importantly there is the dependable police presence and the regular weigh stations along the Panamericana, which are signs of the kind of rule of law that touches on the ordinary business of life (in Marshall’s famous phrase), i.e., commerce. It must be emphasized that this manifestation of the rule of law is the antithesis of that sense of the law mordantly expressed by Anatole France: “The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread.”

The Peruvian desert as seen from the Panamericana -- a photograph cannot do it justice, nor communicate the surprise and passing a gray and barren dune and suddenly coming upon a green and fertile valley.

Rule of law can be an excuse for the powerful to exploit the powerless (thus exemplifying the infrastructure/superstructure dichotomy), as in the Anatole France quote, but rule of law at its best provides a level playing field in which all enjoy equality of opportunity, not equality of exploitation. Also regularly visible along the Panamericana are billboards advertising consumer goods of every familiar kind, which suggests that consumers have disposable income and a choice in how to spend it. It may sound perverse to praise the emergence of a consumerist economy as a virtue, but in comparison to the quasi-feudal economy that preceded it, this represents remarkable progress.

My Exhibit “B” for economic democratization in Peru is the city of Ica. Ica is not well known to tourists, and I did not see another tourist while I was there. If you stay on the Panamericana and breezed through Ica it might strike you as just another dusty town in the desert, and not much different from Nazca. But Nazca, which appears to live almost exclusively off the tourist trade, is quite small, and really appears to be a dusty desert town, whose streets are filled with watering holes for tourists. In Ica, on the other hand, where tourists are not in evidence, the downtown core (some distance from the unattractive aspect presented on the Panamericana) is busy and bustling with locals patronizing all manner of local businesses. While many of the historical buildings in Ica have not been repaired since the last severe earthquake, some traditional facades and arcades are filled with small businesses, attractively placing contemporary commerce in a traditional setting.

My anecdotal account of the Peruvian economy would be no surprise to those who follow statistics and know that Peru’s economy has been growing steadily for many years. When I was last in Peru, in 1994, it had not yet been long that “Presidente Gonzalo” (Manuel Rubén Abimael Guzmán Reynoso) had been captured and Sendero Luminoso demoted from an existential threat to the state to being an occasionally deadly irritant. Fujimori was still in power at that time, but since then several popularly elected presidents have both served their terms in office and have then peacefully handed their power of that office to their successors. There were some worries in the business community when Ollanta Humala was elected, on account of things he said in the past and his political friendships with leftist leaders, but his term so far has brought no destabilizing changes or radical initiatives and the Financial Times has had good things to say about him.

All of this can be gotten from statistics and newspapers; what cannot be gotten from statistics and newspapers is the temper of the people and tone of life. Well, in Peruvian cities the tone of life is loud. Everyone in traffic honks all the time. If you go straight, people honk; if you go right, people honk; if you go left, people honk. Speed up, honk; slow down, honk; stop, honk. You get the idea. But beyond this nerve-wracking clamor, people were spontaneously helpful. Several times, without being asked and without expecting a tip, bystanders helped me to pull out of a tight spot, to maneuver in traffic, and get where I was going when I was not at all certain as to how to do this. There are many cities in the US where you would not encounter this.

In fact, not long ago (in What’s with the attitude?) I wrote about the increasing rudeness of traffic confrontations in Portland. Now, I cannot imagine Peruvian drivers lining up neatly as drivers sometimes do in Portland when there is an obvious traffic queue due to construction or an accident, but I certainly can imagine Peruvian drivers demonstrating spontaneous acts of generosity in the midst of a non-queue. Neither social custom is superior; each simply reveals a distinct manner of acknowledging the humanity of The Other, and this is necessary to a healthy society. Elsewhere I have called this Social Gift Exchange.

Perhaps you think that I have gone on rather too long about in too great detail about roads and traffic, and that this reveals more about myself than about Peru. Perhaps so. Perhaps not. But I will defend my discussion on objective grounds. The model of development that prevails in the Western Hemisphere is predicated upon intermodal transport disproportionately relying on truck transport across highways. Trains are important, but trains will never have the tradition or the economic centrality that they have had in the Old World. In the New World, the truck and the highway are the economic ties that bind.

Elsewhere I have defined (what I call) a Stage 1 civilization as a civilization in which transportation has been globalized so that persons, goods, and services move throughout the world without respect to the geographical obstacles that defined the character of Stage 0 civilizations — when the human diaspora resulted in isolated pockets of civilization, each ignorant of the other. Today, a functioning transportation infrastructure is the price for participating fully — not merely peripherally — in global industrial-technological civilization.

. . . . .

. . . . .

While I am posting this a couple of days after the fact, this entire account was written in longhand on the day here described.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Democratic Institutions

17 July 2010

Saturday

It has become an oft-repeated commonplace that democracy is more than holding elections. This commonplace of political wisdom has come about from the dissatisfying attempts at democratization around the world, when elections have been held but either their mandates have not been heeded or the election becomes a mere stamp of approval upon an authoritarian system that would have ruled in any case.

There was a book published in 2002 by Yale Law School professor Amy Chua titled World On Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability. The book garnered much acclaim as well as criticism. Its basis thesis is that premature free market democracy empowers commercially successful minorities, which in turn causes resentment among dispossessed majorities, which attracts the manipulation and scapegoating of opportunistic politicians. It is a sad story that had been repeated time and again around the world. it is also a story that begs as many questions as it purports to answer. (Moreover, like every other effort of this kind, it cannot deal honestly and openly with questions of ethnicity because it is forbidden on pain of career suicide to do so in the contemporary Western world.)

In other words, the book deals with disproportionately successful minorities and the response of majorities to them, and this has profound consequences for putatively democratic societies — that is to say, societies that have elections but do not have other “democratic institutions.” (Allow me to also point out that there is more than one way to be “successful” as we all know. The definitions of success are many and varied. World on Fire considers commercially successful minorities. The case with academically successful minorities is rather different.) The message here is that elections are not enough, and that societies must have democratic institutions that transcend mere elections if their elections are to foster a truly democratic society.

In this connection one especially thinks of US attempts at nation-building and democratization from the Cold War to the present day. My favorite quote on this (dating from even before the Cold War) can be found Niall Ferguson’s Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power, in the form of a dialogue between Walter Page, a US representative in London, and British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey, regarding the military coup in Mexico in 1913:

‘Suppose you have to intervene, what then?’

‘Make ’em vote and live by their decisions.’

‘But suppose they will not so live?’

‘We’ll go in and make ’em vote again.’

‘And keep this up for 200 years?’ asked he.

‘Yes’, said I. ‘The United States will be here for two hundred years and it can continue to shoot men for that little space till they learn to vote and to rule themselves.’

Niall Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power, p. 291

I am not providing this quote merely for its comedic value, though it is quite funny. More profoundly, it illustrates a striking difference in world views. Niall Ferguson himself takes this lesson from it:

“Since Woodrow Wilson’s intervention to restore the elected government in Mexico in 1913, the American approach has too often been to fire some shells, march in, hold elections and then get the hell out — until the next crisis. Haiti is one recent example; Kosovo another. Afghanistan may yet prove to be the next.”

Niall Ferguson, Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power, p. 315

This is not the lesson that I take from the dialogue. For Ferguson, the British solution would have been to simply take over Mexico. In other words, if the US had followed the British example it would have extended direct US rule — hence American institutions — to Mexico. The American perspective, as represented above by Walter Page, is to start with the minimal democratic institution of elections, and let the locals work things out from there. In other words, to let them work it out their own way. This point of view has come under considerable criticism of late, but I would like to defend it.

There is a familiar litany of the many institutions that contribute to a robust democracy that is more than just the expression of the popular will in holding elections. These include, for example, a free press, separation of powers, an independent judiciary, and, generally speaking, an absence of coercion and violence in the political process. The constituents of this litany are the celebrated democratic institutions that go beyond minimal democratic elections, and they are certainly political institutions that are to be admired. But are they institutions to be copied and replicated? That is another question.

Lately I have been listening, for the second time, to The Teaching Company’s long set of lectures about US History. When I first listened to this a few years ago it made a lasting impression on me. It is quite simply one of the best treatments of US history that I have perused. The Teaching Company has since released a second edition, with different lecturers, but I haven’t listened to this yet, partly because I don’t want to spoil the incredible effect that the original had on me. So I have returned to the first edition and started listening to it from the beginning again, and am enjoying it as much as I enjoyed it before.

The lesson that I am taking from this listening is the extent to which the democratic institutions of the US political system are deeply embedded in the particularities and peculiarities of North American history. More than a hundred years before the American Revolution, some of the distinctive institutions of what is now the US government were already taking shape in the variously constituted colonies. Venerable democratic institutions such as religious toleration, a bicameral legislature, and factionalism culminating in a two-party system, were the product of particular circumstances internal to the development of history in North America. For example, Darren Staloff cites the “Goody Sherman’s Sow” case as the trigger that resulted in a fully bicameral separation of the colonial legislature in Massachusetts.

In so far as what we call “democratic institutions” are deeply embedded in the life and history of the peoples of North America, and of their experience of colonizing a frontier (as well as other experiences, of course), such institutions are not likely to transplant very well into other circumstances that involve other peoples, their lives, and their histories.

What can be said in favor of the minimally democratic institution of elections is that they are quantitative and objective, and for that reason carry with them the fewest traces of cultural identity and peculiarity that make institutions suitable for one people but not necessarily suitable for another people. With elections, we can leave people to sort out for themselves the best institutions that serve their culture in the context of their history. The more we attempt to impose specific institutions on another people, the less likely that imposition is to be successful.

. . . . .

. . . . .

Spreading Democracy: An Historical Perspective

6 February 2009

The ruins of Athens. Thucydides wrote, "I suppose if Lacedaemon were to become desolate, and the temples and the foundations of the public buildings were left, that as time went on there would be a strong disposition with posterity to refuse to accept her fame as a true exponent of her power... Still, as the city is neither built in a compact form nor adorned with magnificent temples and public edifices, but composed of villages after the old fashion of Hellas, there would be an impression of inadequacy. Whereas, if Athens were to suffer the same misfortune, I suppose that any inference from the appearance presented to the eye would make her power to have been twice as great as it is."

Recently in my Ostracism and Deselection I mentioned my listening program in Greek history. There I discussed ostracism in the formal political system of Athens, and the sense in which this realizes the full potential of the franchise. Every pollster knows to distinguish between the “negatives” and the “positives” that a polled topic inspires. Public perceptions are not uniform, and an individual or a topic may have high positives and high negatives at the same time. Anyone who inspires strong reactions — whether for or against — is in this situation. Incorporating ostracism into a political system gives the voters an opportunity to express their high negatives, just as they express their high positives through election to public office. This seems to me to be a good idea.

While on the subject of ancient democracy, and the details of its operation, the past and the present came together for me today as I listened to lecture 14 of Kenneth W. Harl’s series of lectures The Peloponnesian War. The lecture is titled “Triumph of the Radical Democracy”, and Athens was radical indeed in its day. Also today, there was a full page spread in the Financial Times trumpeted on the front page as “Goodbye, Axis of Evil: Barack Obama’s foreign policy is set to embrace ‘smart power’.” Now, who can possibly argue with “smart power”? Certainly it is a wonderful slogan, of the sort that politicians seize upon, as no one is going to argue for “stupid power.” What is “smart power”? On the full page spread, one of the articles is titled “Clinton signals a smart retreat from democratisation.” There’s that word “smart” again.

It seems that smart power is to be a retrenchment from the ambiguities of the Bush Doctrine. Now, the Bush Doctrine is controversial in part because no one really knows what it means. When Sarah Palin was asked in a television interview about the Bush Doctrine many felt that this was an unfair question. (Apparently it never occurred to the critics of the question that someone well-versed in foreign policy might have been able to rattle off a list of possible meanings of the term from the top of his or her head.) One of the possible meanings of the Bush Doctrine was the promotion of democracy abroad. This is both vague and admirable. Like talk of “smart power,” few people are going to argue with promoting democracy. Except now things have changed. If the Bush administration’s foreign policy is what it means to promote democracy, people have decided that they don’t want to promote democracy.

How does this tie in with our ancient democratic forebears? As Athens made its transition under Pericles from being the strongest city-state in the Delian League to essentially dictating the terms of the league and becoming the Athenian Empire, it was engaged in an active program of democratization. When a city-state attempted to defy the Delian League or to leave the Delian League, Athens would, by force of arms, re-take the city, stand up a democratic government, and make that city-state subject to tribute that would be paid to the Delian League, which meant paying tribute to Athens.

Athens was a unique democracy in many ways, and a democracy from which we can still learn, as I implied in my discussion of ostracism. It is difficult to imagine how revolutionary Athens’ actions were in setting up democratic governments throughout its sphere of influence. It was, in fact, so revolutionary that it didn’t take root, and it didn’t spread of its own accord. In fact, democracy mostly disappeared from history after the defeat of Athens in the Peloponnesian War (with some exceptions such as democratic institutions among non-state entities like Vikings and pirates, both of whom lived by raiding others). Democracy did not re-emerge in history until 1776, more than two thousand years later. And it is still revolutionary today. The world was not ready for genuine democracy in Pericles’ day, and the world is not ready for genuine democracy in our day.

It is a lesson for all subsequent Western history that Athens, the source of our culture and our ideals, lost the Peloponnesian war to Sparta. Today we still read Athenian books, imitate Athenian architecture, attend Athenian theatrical productions, and visit Athens itself to see the Glory that was Greece. No one reads Spartan poetry. No one admires Spartan architecture. The Spartans themselves had little use for such niceties. The Spartan state was organized for the purpose of war, and for the purpose of war only, although it was in no sense eager to engage in wars. The Spartans mostly followed the advice of Polonius to, “Beware of entrance to a quarrel, but being in, bear’t that the opposed may beware of thee.”

The Delian League is in pink; Sparta's power (in purple) was mostly limited to the Peloponnesian peninsula.

While the triumph of Sparta in the Peloponnesian War is due at least in part to Spartan military discipline, Athens was a formidable military power itself, especially in regard to its navy. Historical accident also played a role in Athens’ defeat, such as with the famous plague that struck the city during the war and grievously weakened the city. But there is also a sense in which democracy played a role in Athens’ defeat. Not only were there ancient oligarchic and aristocratic regimes that were threatened by Athens’ democratization program, and in threatening them Athens turned powerful vested interests against itself, but there is also another sense of democracy that worked against Athens.

The democratization program of the Delian League under the leadership of Athens set up democratic governments in many ancient cities that had never witnessed anything like it before, and the enfranchised masses appreciated this novel political participation (even if it didn’t last very long). However, the Delian League itself was profoundly anti-democratic, and its policies were dictated by Athens. Athens called the shots, and often acted with impunity in pursuing its interests. In other words, the Delian League was a “Coalition of the Willing.” The Peloponnesian League, under the leadership of Sparta, was much less dictatorial toward its members. Nor were member city-states of the Peloponnesian League forced to conform to the Spartan model. Corinth, an ancient city famed for its wealth, commerce, and art, was a member of the Peloponnesian League. (Corinth was invoked as a symbol of elegance by Gracian, and eponymously named Corinthian capitals, the third of the three orders of Greek architecture, were perfected in Corinth.)

The ruins of Sparta. Note the contrast to the ruins of Athens (pictured above). Thucydides (quoted above) was more right than he could have imagined.

Ideally, there is no reason that we cannot combine the democratic system of Athens, in which each political entity is ruled on the basis of popular sovereignty, with the more democratic practices of the Peloponnesian League, in which members of a confederacy united for a common interest all have a say in the policy of the larger political entity. Ideals, however, are elusive. (The early American republic tried a loose confederation of states and it didn’t work very well.) Also, mollifying the most powerful elements of society, aristocrats and wealthy landowners who are used to having things their own way, is always fundamentally in tension with any efforts to enfranchise the masses. Every society eventually comes to one kind of compromise or another, or it fails.

It is not enough to say that one is going to promote democracy. One must decide what kind of democracy — what kind of democratic institutions and what kind of democratic transparency — one is going to attempt to promote. A foreign policy of democratization might promote actual democratic regimes, or it might seek to create a democratic consensus among existing regimes. Both have been tried in history, with mixed results.

It seems that the emphasis in US policy is going to shift from the Athenian model to the Spartan model. The idea of seeking consensus and collaboration among allies, as has been much emphasized in reaction to the policies of the Bush administration, is clearly a shift in approach. But the exclusive pursuit of either the Athenian model or the Spartan model will ultimately alienate one set of interests or another. It is not so much about making a “smart retreat” from democratization, as the Financial Times would have it, as it is about choosing one model of democratization over another.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .