The Emergence of the Universal Surveillance State

31 March 2014

Monday

The national security state came of age during the Cold War, under perpetual threat of a sudden, catastrophic nuclear exchange that could terminate civilization almost instantaneously at any time, and which was therefore an era of institutionalized paranoia. In the national security state, the response to perpetual danger was perpetual vigilance — one often heard the line, the price of peace is eternal vigilance, which has been attributed to many difference sources — and this vigilance primarily took the form of military preparedness. The emergence of the surveillance state as the natural successor to the national security state is a development of the post-Cold War period, and is partly the result of a changed threat narrative, but it is also partly a response to technological advances. During the Cold War the technological resources to construct a universal surveillance state did not yet exist; today these technological resources exist, and they are being systematically implemented.

In the universal surveillance state, the state takes on the role of panopticon — a now-familiar motif originating in the thought of English Utilitarian Jeremy Bentham, but brought to wide attention in the work of French philosopher Michel Foucault (cf. A Flock of Drones) — which has profound behavioral implications for all citizens. It is well known not only to science but to even the most superficial observer of human nature that people tend to behave differently when they know they are being watched, as compared to when they believe themselves to be unobserved. The behavioral significance of universal surveillance is that of putting all citizens on notice that they are being observed at all times. In other words, we are all living inside the panopticon at all times.

Rather than the rational reconstruction of the state, this is the perceptual reconstruction of the state, in which all citizens have a reason to believe that they are under surveillance at all times, and at all places as well, including within the confines of their homes. The tracking of electronic telecommunications — today, primarily cell phone calls and internet-based communication — means that the state reaches in to the private world of the individual citizen, his casual conversations with friends, relatives, colleagues, and neighbors, and monitors the ordinary business of life.

In order to effectively monitor the ordinary business of life of the presumptively “typical” or “average” citizen, the state security monitors must develop protocols for the observation and analysis of this vast body of data that will differentiate the “typical” or “average” citizen from the citizen (or resident, for that matter) who is to be the object of special surveillance. In other words, the total surveillance state must develop an algorithm of normalcy, in contrast to which the pathological is defined — the “normal” and the “pathological” are polar concepts which derive their meaning from their contrast with the opposite polar concept. Any established pattern of life that deviates from the normalcy algorithm would be flagged as suspicious. Even if such flagging incidents fail to reveal criminality, disloyalty, or other behaviors stigmatized by the state, such examples can be used to further refine the algorithm of normalcy in order to rule out the “noise” of the ordinary business of life in favor of the “signal” of pathological behavior patterns.

Those with a hunger for conformity will perhaps interpret a descriptive algorithm for the identification of normalcy as a prescriptive guide to a life that will not attract the attention of the authorities. Many, of course, will give no time to the thought of surveillance. There will be others, however, who are neither indifferent nor conformist, but who will court if not provoke surveillance. And just as the algorithm of normalcy gives a recipe for conformity, it also gives a recipe for non-conformity. Spectacular instances of non-conformity to an algorithm of normalcy will invite surveillance, and this will have potentially unexpected consequences.

One can only wonder how long it will take for individuals hungry for either fame or notoriety — and not caring which one results from their actions — manage to hack the pervasive surveillance state, pinging the system to see how it responds, and using this same system against itself to catapult some individual into the center of national if not global media attention. One could, I imagine, obtain a number of cell phones, land lines, email addresses, and begin using them to exchange suspect information, and eventually be identified as a special surveillance target. If this activity resulted in an arrest, such an experience could be used by the arrested individual as the basis for a book contract or a legal suit about compromised civil rights. Indeed, if the perpetrator was sufficiently clever they could construct the ruse in such a manner as to implicate “sensitive” individuals or to cast serious doubt upon the claims made by law enforcement officials. Such a gambit might be milked for considerable gain.

Given the currency of celebrity in our society, it is nearly inevitable that such an event will occur, whether motivated by the desire for fame, infamy, wealth, power, or self-aggrandizement. Just as Dostoyevsky wrote in a note appended to the beginning of his short story, “Notes from Underground,” (a passage of some interest to me that I previously quoted in An Interview in Starbucks), such individuals must exist in our society:

The author of the diary and the diary itself are, of course, imaginary. Nevertheless it is clear that such persons as the writer of these notes not only may, but positively must, exist in our society, when we consider the circumstances in the midst of which our society is formed. I have tried to expose to the view of the public more distinctly than is commonly done, one of the characters of the recent past. He is one of the representatives of a generation still living.

The overt celebrity state and the covert surveillance state are set to collide, perhaps spectacularly, the more power that is organized around the universal surveillance state. Given the fungibility of power, the political power represented by the universal surveillance state can be readily translated into other forms of power, such as wealth and fame, and the more political power that in concentrates in the universal surveillance state, the riper is this universal surveillance state to being used against its express intention. In other words, the attempt to turn the state into a hard target through universal surveillance, turns the state into a soft target for attacks that exapt the surveillance regime for unintended ends.

Politicians, while savvy within their own metier, like anyone else, can be woefully naïve in other areas of life, which virtually guarantees that, at the very moment when they believe themselves to secured themselves by way of the implementation of a total surveillance regime, they are likely to be blindsided by a completely unprecedented and unanticipated exaptation of their power by another party with an agenda that is so different that it is unrecognizable as a threat by those who study threats to national security. In the way that hackers sometimes cause mayhem and damage for the pure joy of stirring up a ruckus, hackers of the total surveillance state may be motivated by ends that have no place within the threat narratives of the architects of the total surveillance state.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Fratricide in the Intelligence Community

14 November 2012

Wednesday

The fall of General David Petraeus as CIA chief seemed at first to be a typically petty American political scandal, and I really never can understand how people can get so worked up over this kind of eye-to-the-keyhole politics. It has often been said that US politicians are taken down by sex scandals and European politicians are taken down by money scandals. This pretty much holds true.

Mark Perry, writing in Foreign Policy (Four-Star Egos) attributes Petraeus’ fall to the egoism of American generals, noting that many of them kept mistresses. Comparing Petraeus to MacArthur he wrote:

“Like every great military commander, both boasted an unstinting ambition and an enormous ego, and left a long list of bitter and exasperated enemies within the U.S. military in their wake. Such qualities are a common thread running through our nation’s history — for in the pantheon of great American generals, there has not been a single modest man.”

Now, however, the fall of Petraeus is rippling outward and causing all kinds of odd little stories to crop up, and that is a sure sign that more is going on than meets the eye (even if that eye is firmly pressed to a keyhole). I think this is more about the “bitter and exasperated enemies” than about ego and ambition.

Here are a few of the items of interest, which invite the enterprising analyst to connect the dots (if you can):

● Jill Kelley complains of receiving threatening e-mails from another woman; the FBI investigates, traces the emails to Paula Broadwell, and uncovers evidence of an affair between Broadwell and General Petraeus

● House of Representatives Republican leader Eric Cantor gets a phone call from an FBI agent telling him about the Petraeus-Broadwell affair. This phone call was reportedly made at the behest of David Reichert (see last item below).

● General David Petraeus publicly admits to an extra-marital affair and leaves his post as CIA chief.

● General John Allen, top Afghanistan commander, is being investigated for sending “inappropriate emails” to Jill Kelley, but press reports say nothing about the content of these emails — are they inappropriate because they are threatening or because they are suggestive?

● Paula Broadwell publicly has charged that the Benghazi embassy attack was the result of militants attempting to free prisoners being illegally detained by the CIA.

● Jill Kelley, whose complaint began the unraveling of the scandal, and who has been called a “socialite” and a “social ambassador,” also, as it turns out, is an “honorary ambassador” for South Korea, and in a 911 call suggested that she might be entitled to diplomatic protection.

● Here is what the Financial Times said about an unnamed FBI agent: “The FBI agent who triggered the investigation that led to the resignation of Mr Petraeus sent shirtless photos of himself to Jill Kelley, according to The Wall Street Journal. He reportedly became so ‘obsessed’ by the case that he was banned from it by his superiors. Fearing the case would be ignored, the agent alerted David Reichert, a member of Congress, who raised the matter with the FBI, the paper said.”

Many people receive threatening emails, but few of those who receive threatening emails can interest the FBI in the case, much less get an investigation started, much less have that investigation go so high as to take down a general and the chief of the CIA.

Any of these items taken separately would be odd; taken together, they are more than odd. Knowing that a powerful political figure can be crippled by a sex scandal is an opportunity for anyone to search for dirt. When we reflect that Petraeus was taken down by his own spooks, this suggests discontent at the agency. Actually, it suggests more than this. This expanding “friendly fire” incident in the intelligence community, with a general taken down by his own foot soldiers, points to deeper dissatisfactions — deeper than a socialite-obsessed FBI agent.

Can you imagine one of J. Edgar Hoover’s soldiers taking down the man at the top? Didn’t happen. Wouldn’t have happened. In fact, what did happen was that one of Hoover’s former soldiers, Mark Felt, took down a president by employing all the skills he had learned from his master. The intelligence community is loyal to its own, but this identity can be construed very narrowly — so narrowly that there are rivalries between the intelligence services, and Petraeus may not have been thought (or felt) to be one of the CIA’s “own” by the soldier who took him down.

It is interesting to speculate whether the expansion of the role of INSCOM (Army Intelligence and Security Command) in Afghanistan by way of Project Foundry, which was to be, “a single, ‘one stop’ coordination hub for advanced intelligence skills training and certification across all levels of the modular force,” may have been perceived by the CIA as an infringement of their turf. I have no basis in fact for looking for any connection here, but it is well known that turf battles are a predictable form of inter-service rivalry. INSCOM is military intelligence; CIA is not.

The whole unfolding scandal could be as simple as several men becoming sexually obsessed with the same woman (Jill Kelley, on the receiving end of the attentions of an FBI agent and general John Allen), and David Petraeus following in the time-honored tradition of powerful men taking a mistress. Could be. We can’t rule it out. This is the ideographic dimension of history.

But as analysts we are looking for causality; we want the nomothetic explanation; we want the mechanisms that led to the fall of a general. We accept the ideographic exception as the tip that sets off the chain of events, the contingent trigger, if you will, but triggers activate deeper and more fundamental structures that were there before they were triggered.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Power to the people!

27 February 2012

Monday

Like the Roman god Janus, who had two faces — one looking toward the past, the other looking to the future — all technology has at least two faces, and probably more. When a technology is new one often sees the technology presented either as a threat or a promise, when it is of course both. Internet technology is like this. Both themes are to be found in the popular media: the internet is dangerous and destabilizing (and possibly corrupts the youth, since it provides us with pornography in the privacy of our homes), and the internet is the stupor mundi that will usher in the millennium.

The many faces of any technological development is an important lesson for futurism, since most futurism takes the form of extrapolating a strategic trend developing in the present beyond its present dimensions. In so far as one extrapolates only a single face of a technology, the result is an extremely lop-sided prediction that doesn’t take into account the other faces of the same technology, which often have countervailing influences. This makes for interesting fiction but poor strategy. Strategic thinking needs greater balance. One way to achieve greater balance is through greater knowledge — deeper and wider knowledge.

The internet has vast resources of information for us, but it is a step beyond this information to acquire knowledge. Nevertheless, acquiring information is the first step. Almost everyone uses the internet today; not everyone uses it to inform themselves. Most people are content to use Facebook and to download music and pornography. If, however, you want to inform yourself, you are in a better position to do so now than ever before in human history.

Recently I have been thinking (and occasionally writing) about the extent to which the internet has vastly expanded open-source intelligence to the point that an individual who is suitably motivated can be almost as well-informed as someone with proprietary access to government intelligence. I was once again encouraged to reflect on this by a website that has been brought to my attention, Open Source GEOINT (OSGEOINT). The detail and breadth of information here is astonishing, and I was quite pleased to see that the site links to mine.

Open Source GEOINT (OSGEOINT) represents open source imagery intelligence or IMINT, made available through ever more widely available and accessible satellite and imaging technology. Government with satellites, of course, have much better resolution, and the publicly available imagery intelligence will always lag behind the best government intelligence, but there comes a point where this lag time means little — and it means less and less over time as the publicly available signals intelligence improves.

Genuine signals intelligence (SIGINT) — including electronic intelligence or ELINT and intercepting communications or COMINT — may not be on the open source horizon for some time, but there is a species of signals intelligence (albeit of a tawdry kind) in the newspapers that have tapped in the cell phone calls of celebrities. With this less-than-edifying example in mind, it would not be going too far out on a limb to predict that enterprising hackers may yet provide SIGINT by tapping into the communications of government officials. The Stratfor Hack and the release on Wikileaks of the stolen e-mails represent a kind of ELINT or COMINT.

The internet also provides us with human intelligence (HUMINT). In relation to the Wikileaks diplomatic cables, I mentioned in Once More, With Feeling… that once I had read some of the diplomatic cables that I realized there are many blogs and websites that provide equally incisive insight into the life of nation-states around the globe.

The internet can also provide us with analysis. That’s what I try to do, and there are many others who are also engaged in the task of analysis, though analysis tends to be more ideologically skewed than human intelligence, and far more ideologically skewed than signals or imagery intelligence. There is a simple test that, while not infallible, can be very helpful when it comes to analysis: if the writer is absolutely certain, voices no doubts or hesitation, and never acknowledges an error, then you can be pretty sure that that writer is self-deluded and that their analysis is more akin to ideological venting than to trying to get at the truth.

It is tempting to make the distinction that free content is worth what it cost — namely, nothing — whereas paid content is worth something and that is why people are willing to pay for it. This is not always wrong, but it is also not the whole story. It is also problematic in a context in which business models are being forced to adapt rapidly to technological changes. Many established institutions are going bankrupt because they cannot make money under the changed conditions imposed by the internet.

In the past couple of days I learned the term “paywall,” which refers to the distinction between free and paid content. Paid content is behind a “paywall,” while free content is available to all without restriction. Even sites primarily organized for paid content (like, for example, Strategic Forecasting) will offer some of their content for free. Since I stopped being a Stratfor subscriber I continue to receive their weekly free emails, and for the moment, in the wake of The Stratfor Hack, the site is offering all its intelligence for free. (This will end soon; enjoy it while it lasts.)

Despite website paywalls, a truly prodigious volume of open source intelligence is available. In order to access this information you must have an internet connection and you must either live in the country that does not restrict internet access or learn how to use a virtual private network (VPN). These are essentially economic qualifications. In most industrialized and semi-industrialized nation-states today (as well as urban area in non-industrialized regions) a computer and an internet connection is within reach of most working class individuals. A VPN would cost a little extra, and so would raise the economic bar a little, but not disastrously so.

After you have access to the information, you have to filter, sort, and judge that information. This is really the difficult part — the clincher of the whole thing. In a post I wrote some time ago I characterized objectivity as a talent. This is an unusual assertion, and although I still believe this to be the case, I should add the important qualification that, while objectivity is a talent, even those who do not possess much in the way of intuitive objectivity can cultivate objectivity through effort and application. The reader should be aware that I am fully aware that my focus on objectivity is not in fashion at the moment — there are many philosophers today who deny the very possibility of objectivity. I am unconcerned by this.

Of course, objectivity is only one of a range of intellectual virtues that one must cultivate in order to tease a coherent picture of the world from the vast amount of information available. Knowledge of the world is not a gift; you have to work for it. And the harder you work to inform yourself, the better informed you will be. Unless, of course, you take a dead end.

This is one problem (among many) with conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theories are dead ends with vast amounts of information associated, so if you can’t recognize a conspiracy theory you can waste a lot of time over it. This is where having the right instincts and intuitions is crucial. If you have a natural feeling for what is bogus and what is valid, you can save yourself a lot of time and only focus on the material that is worth your time. If you can’t recognize a waste of time for what it is, this comes with an opportunity cost: the time wasted could have been better spent on valid intelligence.

I have written about conspiracy theories previously (cf. A Reflection on Conspiracy Theories), but it is always important to point out the dangers of unwarranted speculation. If you follow a dead end, you not only waste your time, and possibly also the time of others, you also reduce and perhaps nullify the efficacy of all your actions, and in so doing you remove yourself from any possibility of effecting change or making a difference. The loonier your theory, the more the world ignores you, and rightly so. People want to accomplish practical ends, and they can only do so by practical means. Among these means are the ideas and theories used to make sense of the world. If the theories themselves don’t make sense, then they will never make sense of the world.

The batshit crazy conspiracy theories are easy to identify (if someone is talking about Illuminati or reptilians, that’s a pretty good sign that they’re batshit crazy); the more subtle conspiracy theories are less easy to identify, but they still have characteristics that can be recognized. I have recently come to realize that one of the distinctive things about conspiracy theories is really the lack of a theory. It is a typical technique of the conspiracy theory to selectively present a number of facts or events that prima facie seem to suggest a certain conclusion. The conspiracy theorist then leaves it to you to draw the conclusion. The implication here is that the facts speak for themselves. They do not. I have emphasized in several posts that the facts do not speak for themselves. Facts only can be attributed meaning and value in context, and the more context you have, the more meaning and value you can attribute to them.

Even the more subtle forms of conspiracy theories can be more than a little kooky. Recently a reader comment on my post Spooks and Skullduggery suggested that the mysterious cargo of the Thor Liberty might touch off the next global conflict:

I’m the host of Toronto’s Conspiracy Cafe program. I have been tracking Thor Liberty since it left Finland. It fell off the radar after a rendezvous with a ship called Global Star. Global Star was on the way to India to be scrapped. It has a Russian crew. It made a rendezvous last night with Gibraltar based Fehn Sky in the Mediterranean. Fehn Star sailed from El Ferrol Spain. That’s Spain’s main naval base. They have a contract to dismantle Russian nuclear subs. Global Star is heading for the Suez Canal and perhaps the start of WWIII.

While I am always happy to receive comments, I’m not at all sure how the author got from the various doings of the Thor Liberty after leaving Finland to WWIII. This is what logicians call a non sequiter, though it is at least introduced with a “perhaps.” Perhaps, and perhaps not. Most likely the latter.

Here’s an even kookier example, though in a specifically philosophical context. Below is a reader review from the Amazon.com website for Karl Jaspers The Origin of Goal of History:

This is one of the most significant works of the twentieth century yet it is not even in print. Deep sixed from the word go. Remarkable! Even books detailing the intellectual biography of Jaspers omit mention of it. The various efforts to subject the issues to scholarly study distort the original observations. What’s going on? The reason is not hard to find. It contains the first crystallization of something current science and religion don’t want to face, the phenomenon of synchronous parallel evolution, global in scale, and operating in a fashion that flagrantly contradicts received dogmas of religious, scientific and economic history. Check out the reviewer’s World History and the Eonic Effect for a discussion of this text. Meanwhile it should be reissued and the public deserves to know the existence of this line of historical evidence going back to the nineteenth century. It makes mincemeat of Darwinian thinking. Aha! Now we know why they deep sixed the book.

There are many important scholarly works from the twentieth century that aren’t in print. Fortunately, Jaspers’ work is well known and frequently cited despite its being out of print. Even dyed-in-the-wool Darwinians like me cite the book. I happened across this review on Amazon because I was linking to the book for a post I wrote, since I not infrequently cite Jaspers (Jaspers, like Leibniz, becomes more important to me the older I get). Also, the idea of an “Axial Age” is one of the few ideas of twentieth century philosophy to be widely known outside strictly philosophical circles (like Kuhn’s “paradigm shift”).

The lesson here is simple: don’t be a kook. That should be simple enough, but I’ve gone on at some length about conspiracy theories because I have found that it is apparently rather difficult not to be kook. It seems that the self-educated are especially vulnerable to conspiracy theories, and this has brought discredit onto many autodidacts. One of the valuable functions served by formal education is that an experienced and knowledgeable individual who has been through the process of education guides those who are less experienced and less knowledgeable through difficult epistemic waters where they might otherwise become lost.

I have discussed my views on autodidacticism elsewhere, so I won’t repeat them here. Suffice it to say that the opportunities for self-education in open source intelligence present all the promise and all the dangers of any other branch of scholarship, though with the difficulty of widespread dishonesty superadded. One must read Machiavelli as a primer to all this in order to understand that it is equally important to know the difference between what men say and what men do, and important again to know why these are different and must be kept separate.

With the increasing emergence and accessibility of sophisticated open source intelligence, we are only at the beginning of a curve which may take us in unprecedented directions. In the future we might well see the construction of an entire parallel open source intelligence network, stateless, existing on the internet, and open to all who can gain access. This “parallel” intelligence network is to be understood as dissidents behind the Iron Curtain understood their efforts toward the creation of a “parallel polis”, abandoning corrupt institutions beyond hope of reform and creating parallel institutions to which the disillusioned can turn when they, too, realize that established institutions lack sufficient credibility to bring about needed social change.

The industrialized nation-state system has been as predicated upon a distinction between an elite minority and a disenfranchised majority as any feudal, aristocratic, tyrannical, or despotic government of the past — though today that disenfranchisement is a de facto disenfranchisement. One historical difference between the elite minority and the disenfranchised majority has been the possession of proprietary knowledge by the elite minority. Historical conditions may shift to the point where imperfect knowledge in disequilibrium converges on de facto equality, so that the advantage the elite minority has had through its access to proprietary knowledge is taken out of the equation. Things are still far from equal between between the two social classes, even with intelligence no longer being a decisive inequality, but they will be less unequal than before. This could have profound social consequences.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Trouble Brewing in the Desert

13 February 2012

Monday

The aftermath of the fall of Gaddafi and the violent transfer of power in Libya is beginning to make itself felt through the region. Several stories have come out of Libya itself of conflict between tribes and factions within the country over predictable issues of power sharing, the division of spoils, and acts of revenge and reprisal, as well as conflicts between and among these groups. The transitional government is weak and inchoate, if it could even be said to exist at all. Weakness means vulnerability in the state of nature than exists among nation-stats, and it is inevitable that outside powers will seek to influence events in Libya. One must suppose that spooks and spies from all over the region have been dispatched to Libya, and that some of the disorder in the country is the work of agents provocateurs.

On 11 February 2012 the BBC story Libya’s Saadi Gaddafi threatens to lead uprising reported that Muammar Gaddafi’s son Saadi Gaddafi (who had previously tried to flee to Mexico) appeared on television on Niger threatening to lead a rebellion against the transitional government in Libya. The next day there was a much more detailed story in the Financial Times by Borzou Daragahi in Tripoli, Libya on alert after warning from Gaddafi’s son, which had some interesting information on the strained relations between the transitional government in Libya and the nation-states of sub-Saharan Africa. Muammar Gaddafi had curried favor in the region by spreading Libya’s oil money around; that largess has come to a screeching halt, with the predictable consequence that nation-states in the region are suddenly sentimental for the ex-Libyan strongman.

Muammar Gaddafi liked to dress the part: here he is seen with other now-deposed North African heads of state, who chose the Western business suit look. Is Saadi Gaddafi seeking the constiuency once served by Mubarak, Zine el Abidine Ben Ali, and others?

Interestingly, in this television appearance Saadi Gaddafi is wearing an expensive-looking Western business suit, sitting in a large overstuffed leather chair, and surrounded by symbols of wealth, opulence, and power. He looks, to put it plainly, like he is seated in an office of executive power. This is clearly meant to send a signal, and that signal is this: I’m alive, I’m in control, I have money and backers and influence and you can’t touch me. While this is a powerful signal, it is also not exactly what I would have expected. His father made much of cultural appeals, often dressing the part with theatrical panache. when the elder Gaddafi wanted to appeal to Arabs, be positioned himself as a Arab and dressed as one. When he wanted to appeal to Saharan and sub-Saharan Africans, he positioned himself as an African and dressed the part, and would engage in heated anti-Arab diatribes. So what is Saadi Gaddafi’s intended constituency when dressed as a Westernized businessman? The obvious answer would be “western businessmen,” but in this case I do not think that the obvious answer is the correct one. I will wait for more clues before I hazard any more guesses on this head.

In the map above I have put numbers in the nation-states indicating the number and location of Muammar Gaddafi’s surviving children: Saadi Gaddafi is in Niger, Saif al-Islam is at home in Libya, a prisoner of the transitional government, and in Algeria there are Muhammad al-Gaddafi, Hannibal Gaddafi, and Ayesha al-Gaddafi. Interestingly, the Gaddafis in Algeria have been quite silent, whereas Saadi in Niger is in front of television cameras — precisely the reverse of what I expected. And then I put a star in Mali to represent the clashes there.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the Sahara, Tuareg tribesman who served as Muammar Gaddafi’s mercenaries for many years (read: well-trained and well-armed) have returned to their native regions, mostly in Northern Mali but, being nomads, they travel across Algeria, Niger, Chad, and Libya as well, and are reinvigorating an old insurgency of Tuaregs against the Malian government based in Bamako. I say, “based in Bamako,” because if you look at a map you will see that there is a lot of desert between Bamako and the Mali-Algerian-Niger border region. It will be extraordinarily difficult for the government of Mali to effectively project power in this periphery, and especially so against desert nomads who call the region home. Strategic Forecasting has published an excellent analysis of the Tuaregs in Mali, Mali Besieged by Fighters Fleeing Libya, which details some of the problems that Malian government is having and will have.

The government of Mali claims that the Tuareg rebels are affiliated with al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), while the Tuaregs make the counter-claim that they will be a bulwark against AQIM. In other words, AQIM is in play in Mali. At the same time, other al Qaeda identifying representatives have urged support for the rebels against the Syrian government. The relationship of this to North Africa is distant, but, I think, still significant. Notwithstanding the fact that Syria is ruled by the minority Alawites, who are Shia, and al Qaeda affiliated groups tend to be predominately Sunna (which would make the al Qaeda support of Syrian rebels comprehensible under any circumstances, and therefore not surprising), one can see this as a preemptive move by rump al Qaeda elements to get back in the game after having had most of their apex leadership killed. The relation to the Sahara is that a similar dynamic could emerge here, with al Qaeda shifting its focus from its traditional preoccupations to supporting the overthrow of regimes of all kinds, so that the ensuing chaos might be exploited. With this stance comes the popular sympathy and street cred of having sided early with rebels who are ignored by other powers, and therefore being in a position of disproportionate influence should those rebels prove successful.

We now recall, in this context, that the elder Gaddafi himself tried to play both sides of the al Qaeda card, at one moment warning the Western powers (essentially), “Après moi, le déluge,” while at another moment trying to hijack popular Islamic sentiment by seeming to align himself with the goals of al Qaeda. Thus one message that Saadi Gaddafi’s business suit may be intended to send is that, “I’m not al Qaeda,” but, of course, he could change that with his next television appearance. And, also of course, there is a diplomatic advantage to being unpredictable, especially when acting against the predicable purposes of established nation-states.

In The Gaddafi Diaspora I suggested that:

“…North and Central Africa are complex crossroads, made all the more complex by recent events. With all these forces in play, the Sahara Desert may become a periphery that decides the fate of the political centers of the region. The momentum of history, at least in Africa, has passed into the vast emptiness of the interior of the continent. This will be a theater to watch in coming years.”

I continue to think that the Sahara may yet prove a disruptive theater in future African affairs.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Spooks and Skullduggery

21 December 2011

Wednesday

Two news stories today underlined Chinese dedication to the incremental accumulation of intelligence by way of a kind of espionage gradualism that eschews cloak and dagger operations as well as spectacular “crown jewels” kinds of intelligence coups in favor of a broadly-based campaign to collect all that it can collect by whatever means possible. China is well known in the intelligence community for its cultivation of “open source” intelligence, which means that Chinese agents comb through vast amounts of readily and legally available information, sending back whatever is thought to have some value. Given a base population of well over a billion people, one can easily understand the efficiency of this method for the Chinese.

The Chinese are not likely to have a big spy ring caught or deported, after the fashion of Anna Chapman et al., but they sometimes push the limits and go beyond what is strictly open source. When they do so, they rarely do so by way of cash or sexual favors, which are perhaps the most common inducements in Russian and American spy rings, but the Chinese rather appeal to the Chinese ethnicity of well-placed individuals (rather than attempting to establish networks of individuals, which then in turn seek to insinuate themselves into sensitive positions) to induce them to transfer sensitive information and technology to China.

A perfect example of this is the industrial espionage case in which Ke-xue Huang admitted to stealing trade secrets from Dow AgroSciences and Cargill Inc. and sending them to China. Ke-xue Huang is a Chinese national with permanent resident status in the US. Today the BBC reported that Ke-xue Huang was sentenced to seven years in prison in Chinese scientist Huang Kexue jailed for trade theft.

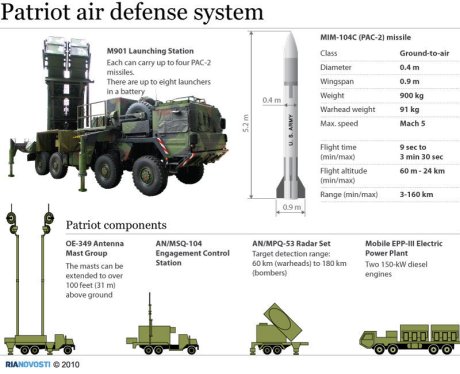

The BBC also reported today the detention of the Ukrainian-crewed, Isle of Man flagged ship M/S Thor Liberty at the Mussalo container terminal at Port of Kotka, Finland, in Finland ‘finds Patriot missiles’ on China-bound ship. Port workers noticed carelessly stored explosives on the ship and did more poking around, which led them to 69 Patriot missiles in crates labeled as “fireworks.” The ship was bound for Shanghai (as well as South Korea), but of course there was no documentation connecting the missiles with a Chinese destination.

One could interpret this shipment of Patriot missiles as an extraordinarily sloppy piece of skullduggery, which would make the Chinese look foolish and incompetent. Are they? I don’t think so. One could also interpret this shipment as a low-risk, low-payoff piece of skullduggery very much in line with known Chinese espionage methodology. Its seizure is without question an embarrassment, but not likely the cause of an international incident. Patriot missiles are widely sold to US allies. The Chinese could probably obtain them in other ways. Perhaps the opportunity presented itself to obtain a cargo ship full of them, and the very marginality of the operation was an attraction for the little attention the ship would attract.

Every nation-state in the world has laws against espionage, yet every nation-state in the world operates espionage networks, and is always on the lookout for espionage networks operating on its own soil. It is very much a cat-and-mouse game. The Chinese prefer to chase lots of small mice with lots of small cats. The US and Russia tend to have a few larger cats chasing a few larger mice. Each method has its advantages and its disadvantages.

A really spectacular piece of skullduggery can have a huge payoff, but if the spy ring is cracked or turned, there can be an equally large payoff in the unintended direction. Espionage is particularly vulnerable to unintended consequences. And when the stakes are high, it is a deadly game, and assets lose their lives. From this perspective, Chinese espionage methodology looks risk averse.

It ought also to be pointed out that spectacular intelligence assets can be wasted, as I attempted to describe in Missed Opportunities: CIA Spies in Iran. If great risks are taken to place high level spies in valuable positions, but the intelligence gleaned from such operations is frittered away on short term advantages, then you have put your assets in a dangerous position on an indefensible pretext.

The coming days will likely reveal more about the M/S Thor Liberty, though it will likely be months or years before the public gets the story, as with the case of the M/V Faina, the story of which only came to light as the result of Wikileaks. So here is one more plug for Wikileaks, Pte Bradley Manning, now in pre-trial hearings, and Julian Assange, soon to be extradited to Sweden. The poor man’s intelligence network — that is to say, the intelligence network open to you and me — is constructed from leaks, blogs, tweets, private correspondence, and any other source we can cultivate. Without this quasi-Chinese open source intelligence network, we would be even more utterly in the dark than we in fact are.

. . . . .

The Finnish site portti.iltalehti.fi has this detailed information on the M/S Thor Liberty:

Name: Thor Liberty

IMO: 9065273

Flag: Isle Of Man (uk)

MMSI: 235218000

Callsign: ZNGT5

Former name(s):

– Cec Liberty (Until 2009 Oct 28)

– White Rhino (Until 2008 Nov 06)

– Cec Liberty (Until 2007 Dec 03)

– Cec Hope (Until 2002 Nov 28)

– Cic Hope (Until 2001 Nov 21)

– Arktis Hope (Until 2000 Jan 04)Administrative Information

Home port: Isle Of Man

Class society: Lloyd´s Shipping Register

Build year: 1994

Builder*: Nordsoevaerftet

Ringkobing, Denmark

Owner: Habro Kongea

Copenhagen, Denmark

Manager: Greenstar Steamship

Haren Ems, GermanyTechnical Data

Vessel type: Cargo

Gross tonnage: 3,810 tons

Summer DWT: 5,392 tons

Length: 97 m

Beam: 16 m

Draught: 5Port history

2011 December 11th, 21:00:06 UTC Kotka

2011 December 6th, 11:00:32 UTC Emden

2011 December 3rd, 09:00:40 UTC Papenburg Germany, probable loading port

. . . . .

Note Added 27 December 2011: Since I wrote the above there have been several news stories claiming that the Patriot missiles were a legitimate shipment of second-hand German missiles that had been purchased on the up-and-up by South Korea, and in fact the M/S Thor Liberty was scheduled to make port in South Korea before heading to Qingdao. Cf. Finland questions Germany-South Korea missile shipment and Germany: Patriot missiles impounded in Finland were legit shipment to South Korea. This is plausible story, but I remain skeptical that it is the whole story or the correct story. If I were the captain of a ship with both missiles and explosives on board, I would want to make a minimal effort to make sure my papers were in order. Since it was the Germans who confirmed the legitimacy of the missile shipment to South Korea, I have to wonder if the Germans routinely ship weapons systems without adequate documentation, and, if they do, how they assure that these weapons systems are off-loaded at the correct port and transferred to the intended purchasers. And, again, if I were the captain of a ship transiting winter seas with both missiles and explosives on board, I would want to made some kind of effort to make certain that the explosives were properly restrained and did not present a danger during the voyage. According to Finnish customs officials, the explosives did pose a danger in high seas.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Spook Week

11 October 2011

Tuesday

It’s been a busy week for the spooks! Indeed, so many spooks have been putting in a public appearance that one might suppose Hallowe’en had arrived early this year.

Not long ago in Dancing with Spooks I commented on the dialectic of public and private diplomacy, and wrote that, “Public diplomacy often serves its most crucial function when it contradicts private diplomacy.” This observation could well be reformulated as a principle, to the effect that if one message is being broadcast by way of public diplomacy, then it is more likely than not that the opposite message is being transmitted by private diplomacy.

At the moment, the headlines are all about the arrest of two Iranian men in the US whom US officials claim were involved in a plot to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the US Adel al-Jubeir. According to US Attorney General Eric Holder, the alleged conspiracy was “conceived, sponsored and directed from Iran.”

While it is entirely possible that there is a tenuous thread of truth in these claims — it is being said that Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps was involved in the planning, and it is possible that rogue extremist elements within the IRGC did have a plot afoot; note that UK Prime Minister David Cameron’s office cited “elements of the Iranian regime” but left it at that — it is unlikely in the extreme that any such plan was conceived and directed at the highest levels of Iranian state power.

Why? Assume the plot was successful, and that two Iranian Americans (one held passports from both countries) with easily traceable ties to Iran, murdered the Saudi ambassador to the US on the US soil. It would be difficult to overestimate the catastrophic fallout from such an event. It would be considered, in the eyes of most, to be a provocation that demanded a robust US response. Moreover, it would demand a robust response from both the US and Saudi Arabia. This would be a legitimate pretext to take military action against Iran of the sort that could not be taken unilaterally without grave international consequences.

Such a scenario would be a nightmare for Ahmadi-Nejad, and one must assume that such actions would be undertaken by elements within Iran that wanted to deal a critical blow to the current Iranian regime, rather than by Ahmadi-Nejad’s supporters, who have everything to lose and nothing to gain by a provocation of this magnitude.

The extremely public way in which the US administration is handling the public diplomacy of the alleged plot reveals how much hay can be made from a failed plot of this nature. Had the plot been successful, it might have been a game-changer for the Arabian Peninsula and its relations with the US. It is to be expected, then, that such an enterprise would be “conceived, sponsored and directed” by those who would want to change the game in the Arabian Peninsula, and those who would want to see robust US-Saudi retaliation against Iran.

Somewhat less public, but equally obvious, was an op-ed piece in the Financial Times, It is time to take on Pakistan’s radical jihadist spies by Mansoor Ijaz, an ethnic Pakistani with long standing ties to the US defense establishment.

Interestingly, Mansoor Ijaz gives some of the backstory of Admiral Mike Mullen’s very public diplomacy that I mentioned in a note added to Dancing with Spooks, which suggests that Admiral Mullen’s public diplomacy was preceded by private diplomacy aimed at the military leadership of Pakistan, warning them away from unseating President Zardari in response to the national humiliation of the UBL kill or capture commado raid.

While Mansoor Ijaz’s piece in the FT is interesting, and fills in some blanks, most of it reads like the script to a B grade spy flick. Here’s a typical sample:

“ISI embodies the scourge of radicalism that has become a cornerstone of Pakistan’s foreign policy. The time has come for America to take the lead in shutting down the political and financial support that sustains an organ of the Pakistani state that undermines global antiterrorism efforts at every turn. Measures such as stopping aid to Pakistan, as a bill now moving through Congress aims to do, are not the solution. More precise policies are needed to remove the cancer that ISI and its rogue wings have become on the Pakistani state.”

Well, yes. We certainly would all like to shut down organs of radical militancy that pose a clear and present danger to global civil society. Yes, but how? Not the bill moving through Congress. What then? More precise policies. What policies exactly, then? Here we get no help. I wouldn’t argue against “more precise policies” any more than I would argue against shutting down organs of radical militancy. Very few westerners would argue against these obvious measures. But it gives us nothing to go on, because it gives us no specific measures that might be undertaking.

Mansoor Ijaz also mentions a shadowy division within Pakistan’s ISI, “S-Wing,” which is reportedly tasked with liaising with the Taliban, al Qaeda, and the Haqqani network — in other words, everybody’s list of militant heavies with their faces on dart boards. Ijaz actually writes, “S-Wing must be stopped.” I half expected to read, “S-Wing delenda est.” In any case, there is an interesting article on the ISI’s S-Wing on the Threat Matrix blog, which quotes an article from the Times of India — not the most objective source when it comes to analysis of Pakistan — in the attempt to give a little background to S-Wing so it didn’t look too much the part of the counter-terrorist’s deus ex machina.

Since Mansoor Ijaz’s FT piece contains no concrete proposals to tame the ISI or shut down its now-or-soon-to-be-notorious S-Wing (and I might point out that I did offer concrete proposals in Colombia, Algeria, Peru, Pakistan), it’s only purpose can be rhetorical: to introduce S-Wing to the news-reading public, to emphasize the weakness of Pakistan’s civilian government (no news there), to drive home the message of alleged Pakistani involvement in militant jihadism, and to ridicule Pakistan’s pursuit of strategic depth through involvement in Afghanistan.

I don’t necessarily disagree with Ijaz, but the way in which he has publicized his views leaves many more questions than answers. As I noted above, he offers no steps, methods, policies, or proposals to ameliorate the situation in Pakistan. How is this helpful? Inquiring minds want to know.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Dancing with Spooks

9 September 2011

Friday

Happiness, remembering the night of drinking and dancing, dancing by myself like a peasant, a faun, with couples all around me.

Alone? Actually: There we were dancing face to face in a potlatch of absurdity, the philosopher — Sartre — and me.

I remember whirling about, dancing.

Jumping, stomping down the wooden floor.

Acting rebellious and crazy — like a fool.

For me, there’s a connection between this dance, with Sartre oppsite me, and a painting I recall (Picasso’s Demoiselles d’ Avignon). The third character was a store-window dummy made out of a horse’s skull and a flowing, striped yellow and mauve dressing gown. A grimly medieval canopied bed presiding over the fun.

Five months of nightmare ended in a carnival.

What a surprise — fraternizing like that with Sartre and Camus (I’m talking like a schoolboy).Georges Bataille, On Nietzsche, VII, p. 73

If there is anything more surreal and hallucinatory than Bataille’s account of “dancing” with Sartre, it would have be to the diplomatic dance of nation-states and especially of the spooks, spies, agents, and diplomats who ultimately make it all possible. Diplomacy makes for some strange bedfellows, and so it makes for great stories. Not surprisingly, many of the best films of the twentieth century were spy thrillers of one sort of another, from The Lady Vanishes to Enemy of the State — and, of course, the spy thrillers haven’t stopped just because we’re in a new millennium.

One of the amazing things about espionage is that the true stories are often more shocking and surprising than the fictionalized stories of the cinema. Alfred North Whitehead had an explanation for this:

“Literature must in some sense be believable, whereas experiences of human beings in fact develop beyond all powers of conjecture. Thus Social Literature is conventional, while History exceeds all limitations of common sense.”

Lucien Price, The Dialogues of Alfred North Whitehead, Prologue

The true stories, however, if they come out at all, come out so long after the events in question actually transpired that the world has moved on. The fictionalized stories come to us as events are unfolding, and so we recognize in them the truth of our time. But it is not the whole truth. Recent revelations from Wikileaks and from files recovered in Tripoli after the Gaddafi regime abandoned their capital in an unseemly rush is showing us, in real time, some of the sausage-making machinery of diplomacy.

And, of course, this is not limited to Libya. I noticed a very small item in the Financial Times earlier this week (on Tuesday 06 September) that explicitly noted the involvement of the US in the ISI capture of Younis al-Mauritani. The next day this item appeared in more detail on the Voice of America (US-Pakistan Joint Raid in Pakistan Viewed as Rare, Hopeful Sign for Troubled Ties) where it was spun as a “rare, hopeful sign.”

The VOA story makes an odd claim:

“Ties between the intelligence agencies of Pakistan and the United States have been severely strained since the killing of Osama bin Laden in a covert U.S. raid in Pakistan in May.”

“Both sides have attempted to play down the tensions through public statements, but the expulsion of American security personnel by Pakistan and the suspension of some U.S. military assistance have highlighted the distrust on both sides.”

“Severely strained” is right, but the following paragraph is what strikes me as a bit odd. The public diplomacy has in fact been quite rancorous, and if this is what counts as “playing down” tension it would be frightening to see what escalating tensions look like. But now we see these tensions of public diplomacy in context, and the context is that of continuing cooperation between US intelligence and diplomatic services and the Pakistani ISI (Inter-Services Intelligence), which latter is so notorious that it is frequently called “a state within a state,” is known to have had close relationships with stateless militants, has recently been accused in the assassination of a journalist, and is usually presumed to be a loose cannon beyond the control of Pakistan’s civilian leadership.

What has emerged from Libyan secret police files is that Libya’s intelligence agency (the Mukhabarat el-Jamahiriya), led by Moussa Koussa, was actively working with several intelligence agencies of Western powers — obviously, the CIA and MI6, but not only the British and the Americans. The US and the UK were involved in renditions that brought targeted individuals to Libya for questioning, and one assumes that these interrogations would not have observed the niceties that Western nation-states and their intelligence operatives must at least appear to respect.

After Gaddafi’s regime accepted responsibility for the Pan Am Flight 103 attack (the Lockerbie bombing) and the UN Security Council voted to lift sanctions against Libya on 12 September 2003, and then Libya formally renounced its WMD programs on 19 December 2003, it seemed that Libya was making a good faith effort to re-join the civilized nation-states of the world. The WMD programs were dismantled to international specifications, and relationships between Libya and the Western powers began to lurch toward normality. This reconciliation must also have involved increasing contacts between Libya and Western intelligence agencies. In fact, we now know that these intelligence relations became so close that the US and UK were using Libya for its extraordinary renditions.

It is important to point out that this close relationship between intelligence agencies did not save Gaddafi. The notorious Moussa Koussa resigned his position in the Libyan regime and fled to the UK, where he is still “in custody” (which could mean any number of things, from being held in a dank cell to enjoying a rather comfortable house arrest). Even while the US, the UK, and other Western powers began to work with Gaddafi, when they saw their chance to be rid of him, mostly they did not hesitate. (One suspects that intelligence relations with the ISI have a similar character.) Even in his reconciled state, Gaddafi was a pariah — had made himself into a pariah.

There are all kinds of lessons that can be taken from this drama. No one lesson is entirely right; no one lesson is entirely wrong. Therefore, to learn only one lesson is to learn the wrong lesson. The world is a complicated place. Some day perhaps someone with the requisite experience, knowledge, and theoretical acumen will write a definitive treatise, The Philosophy of Espionage, in which the complexities and contradictions of the secret side of the relationships between nation-states will be laid bare and analyzed with a dispassionate eye. I hope I live to see that text.

The people who conduct these backroom deals with others whom they know to be brutal and unscrupulous representatives of brutal and unscrupulous regimes are put in a difficult position. They literally must learn to live a lie. Every day they find themselves justifying their actions in terms of the end justifying the means, which they must know in their heart-of-hearts falls far short of even a modest human ideal for a moral life.

And the lying starts immediately. One of my sisters once attended a CIA recruitment event. They had advertised in the local newspaper for people who wanted a career that involved foreign travel. At the very first acquaintance with the CIA, prospective employees were told not to say anything about their initial meeting with CIA representatives to families, friends, and loved ones.

Dancing with spooks is not for the faint of heart, and it isn’t going to go away anytime soon. So, being the Socratic fundamentalist that I am — that is to say, I truly believe that knowledge is virtue — it is better to know it and understand it. The alternative is to pretend it doesn’t exist and hope it will go away. It won’t. Spooks are here to stay, and that’s why we need someone to write a Summa of espionage.

. . . . .

Note added Thursday 22 September 2011: It was widely reported today that outgoing chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen, speaking to a US Senate panel, accused Pakistan’s spy agency of supporting the Haqqani group in last week’s attack on the US Kabul embassy. Mullen was quoted as saying, “The Haqqani network… acts as a veritable arm of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency.” Note that this is “public diplomacy.” No one of Mullen’s stature says something so inflammatory for media consumption without approval at higher political levels. There are many things that could be going on here, so soon after the above mentioned “rare, hopeful sign.” There may be elements within the ISI that have gone rogue, and this is a warning by the US for Pakistan to bring it under control. There may be political division within the ISI or within Pakistan’s civilian leadership, and the US in wants to warn them about any choice that might come out of such a dispute. It may simply be for US domestic consumption, to remind people that the US works with the ISI but doesn’t trust it. Public diplomacy often serves its most crucial function when it contradicts private diplomacy.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Signals Intelligence and American Culture

30 March 2009

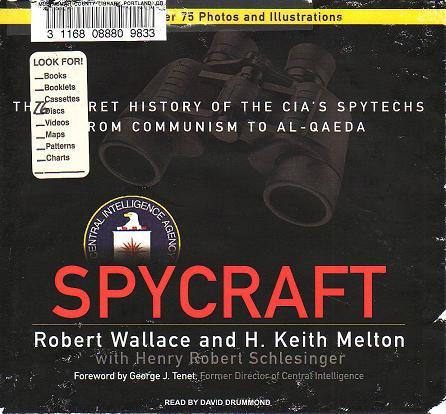

Recently I started to listen to an audio book about intelligence gathering technology, Spycraft: The Secret History of the CIA’s Spytechs from Communism to Al-Qaeda, by Robert Wallace and H. Keith Melton. In The Dialectic of Stalemate I previously expressed my admiration for several espionage and intelligence technology books such as Skunk Works, Blind Man’s Bluff, and Operatives, Spies, and Saboteurs, so I am looking forward to this book.

Why does the US have the sophisticated signals intelligence program, and the technological wherewithal to carry it out, that it does? The short answer is this: because we can.

As we all know, beyond the short answer (with all its dissatisfying oversimplifications) is a long answer. A sketch of the long answer follows.

When the US began its career as an independent nation-state following upon its successful revolution, It did not have the power to play at great power politics. The new country, with its Articles of Confederation and its Continental Congress, was inexperienced, small, relatively poor, quite weak, and very distant from the center of things, as the center was then understood. Robert Kagan, in his excellent (and admirably short) book Of Paradise and Power: America and Europe in the New World Order (p. 7), emphasizes that the founders were aware of their lack of resources and would have been entirely willing to play at power politics had they the ability to do so.

Kagan argued that the US founders argued against foreign entanglements not due to any principled objection, but simply because they didn't have the resources to play the Great Game.

An indirect result of the relative impotence of the young US was the Monroe Doctrine. We will not explore this at present, as it is a large topic, but it should be mentioned that US power focused on keeping European interference out of the Western hemisphere at a time when it had itself not the resources to project power in the Old World. The Old World, by contrast, did possess the ability to project power in the New World, which is why the American Revolution was a close run thing, and the US was surrounded in its hemisphere by colonies of Europe. Spain was a declining superpower, but it still controlled all of Latin America to the south; the English still controlled Canada to the north.

The Monroe Doctrine was more about the inability of the US to project power globally than an expression of a principled US foreign policy.

Generally speaking, people do what they can with what they have. I can recall reading about archaeologists expressing their admiration for the quality demonstrated by early spear points (especially Clovis points) and by the stitching on Ötzi the iceman’s intact clothing. When one pauses to think about it, it is not surprising. This is the only technology early peoples possessed; they would have had lots of time to spend on it, and lots of time and opportunity to get it right.

Some scientists expressed surprise over the high quality workmanship of the iceman's possessions, but what else would have occupied the spare hours of Ötzi's people during those long nights around the campfire?

Even the poorest countries can get involved in human espionage. Pakistan’s ISI, for example, has a legendary reputation in the field. Basic tradecraft for human intelligence is relatively inexpensive, and bribes probably play little role in most intelligence operations. (One would suppose that sexual favors are among the most effective bribes, when properly used, and these can be inexpensive to provide. Not everyone spends as much as Eliot Spitzer for a liaison.)

Since the poorest nation-states would be mostly limited to human espionage, one can expect that their poverty, as well as the relentless competition, would force them to be creative. As we noted above, people do what they can with what they have (call it a principle if you will). All countries have a few clever people, and we can expect that they would use these resources to their best advantage in gathering and analyzing human intelligence. Here’s another principle, while we’re doing principles: limitation is the mother of invention. It is not only necessity that drives innovation. Being forced to work within certain bounds frequently forces people to use their utmost creativity to derive innovative solutions. (An example of this was the creativity of Hollywood when operating under the restrictions of the Hays Code.) And because these solutions are innovative, they are also difficult to predict and carry with them the element of surprise.

Because of its economic and technological resources, the US is not limited to human intelligence. US signals intelligence is almost without question the best in the world. All the creativity and innovation that other nation-states bring to human intelligence, all the same enthusiasm and ambition and pride in accomplishment, are expressed in the US through its technological triumphs.

The US has a technology- and innovation-friendly culture. I previously noted in Social Consensus in Industrialized Society that the US is the society that has been most shaped by the Industrial Revolution. As a young society when the Industrial Revolution began its transformation of the Western world, the US had the fewest historical traditions, and the strongest historical tradition present throughout our institutions was that of the Enlightenment, which was, among the stages of Western history, that most favorable to the exercise of reason.

US cultural institutions embodying the Industrial Revolution and the Enlightenment not only tolerated innovation in science and technology, these were positively encouraged and took on a life of their own as a result. And when it comes to warfighting and espionage, the US has pressed its competitive technological advantage to the utmost, and continues to do so. The US can do signals intelligence better than almost anyone else, so that’s what it does. But there is more.

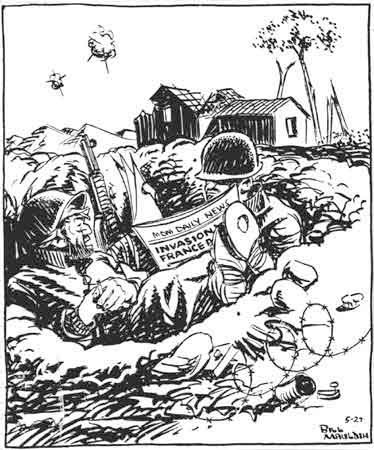

This famous Bill Mauldin cartoon, with the caption, 'Th' hell this ain't th' most important hole in th' world. I'm in it.' clearly expresses the democratic value placed on individual human life.

The broadly democratic values of the US also contribute to the cultivation of signals intelligence. Life in the US is not cheap, as it is in many places in the world. Every soldier (including the non-uniformed soldier in espionage) values his own life as highly as anyone else, and the widespread belief in self-worth has forced US military institutions to adopt policies that reflect the value of the individual life. It is inconceivable today that the US would fight battles like Verdun and the Somme, and even during the First World War Pershing could see that he did not want his troops to operate under the European commands that brought about these disasters. When the American Expeditionary Force arrived in Europe, France and England wanted US forces to be gradually added to their exhausted forces in the trenches, but Pershing insisted on all-US units fighting under the US flag and under US command.

John J. "Black Jack" Pershing in October 1918 during the First World War. Pershing insisted on US troops fighting under US command when European allies wanted to integrate US forces into European armies under European command.

The professionalization of the US military following the end of the draft was another development that emphasized the value of the life of the individual soldier. This same trend valuing the life of the individual soldier as a trained professional with valuable experience, not as a sacrifice to be slain for the good of the nation, is now almost being expressed in another high technology initiative: unmanned aerial assets. There is talk in the defense community that the current generation of fighter jets may be the last generation of manned fighters.

An early version of the Predator UAV (note the absence of missiles under the wings). UAVs began as surveillance aircraft, with armaments added later. Many in the defense establishment see this as the future of combat aviation.

Intelligence operations can be as dangerous to human intelligence operatives as the battlefield environment is to the soldier. If technological innovations can spare the life of a human agent, then the US can be expected to push this alternative to the limits of its possibility. Thus the rationalism of the Enlightenment and its emphasis upon science, the competitive advantage afforded by advanced US technology, the democratic emphasis upon the equal value of all human life, and the professionalization of the military have all come together to create a US intelligence culture focused on signals intelligence.

. . . . .

. . . . .