The Technocratic Elite

21 December 2014

Sunday

One of the most fascinating aspects of civilization is how, despite thousands of years of development, radically different social, economic, and political systems, and the rapid growth of technology since the industrial revolution, there are structural features of civilization that do not change in essentials over time. (I have previously discussed these civilizational invariants in Invariant Social Structures, Invariant Properties of Civilization, and Invariant Civilizational Properties in Futurist Scenarios.) One of these invariant structural features is social hierarchy, and more specifically the fact that, all throughout history, a tiny fraction of the population has been in a position of political control, while the vast bulk of humanity has been subject to the control of a small minority.

The existence of a power elite, as a civilizational invariant, implies that there is always a power elite in every civilization, though this power elite may take different forms in different civilizations, and throughout the history of a given civilization the power elite may shift among individuals, among families, among ideologies, among industries, and even among social classes. From the perspective of the big picture, who happens to hold power in a given society is a mere accident of history, and the interesting feature is that there is always a small elite that holds power.

The “big lie” of our time is that the power elite that currently graces our society is in its position as the consequence of meritocratic mechanisms that assure only the best will achieve the pinnacle of power. Thus the ancient idea of aristocracy (rule by the best) is preserved, but given a contemporary, democratic twist in the assurance that anyone can be selected by these social mechanisms for advancing and rewarding talent. Now, this “big lie” is no worse than any other big lies around which societies have been constructed — no worse, for example, than Plato’s “noble lie” — but no better either.

We may call the power elite who benefit from this “big lie” of industrial-technological civilization the technocratic elite. They are few in number, and essentially oligarchic. (A recent study, Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens, reported on the BBC in Study: US is an oligarchy, not a democracy; many studies have demonstrated similar findings.) That our elite is a technocratic elite does not reflect upon the quality of individuals who belong to the elite, but rather the kind of civilization that happens to arbitrarily raise up a few individuals into positions of power. The nature of this civilization is such that it shapes its power elites in particular ways that are enabled by the technological means of mass control.

It is not difficult to spot the technocratic elite (apart from the obvious fact that they appear on the news and on the glossy color covers of magazines). They are in excellent health and are dressed well, though in an understated style. Good food and good clothes are expensive. One must also have the leisure to be able to care about such things: they have time to exercise and to eat right. Just the right amount of education in just the right schools to give just the right mid-Atlantic accent accounts for the elocution and steady, careful tone of voice. They have been taught to express superficial concern for the lives of others, and they spend just the right amount of time on just the right charities to achieve just the right amount of media exposure for their time investment. These are not qualities of the individual, but rather qualities conferred upon the individual by their unique position in a technological society.

In A Thought Experiment in Tyranny I asked:

“If the president of a given nation-state belongs to a class of wealthy, world-traveling, foreign language-speaking elites with more in common with other elites than with the people of the nation-state in question, is this local rule or foreign rule?”

While from the perspective of the ruled it matters immensely (and is sometimes a pretext for revolution); from the perspective of the technocratic elite it is irrelevant. The particular nation-state of their citizenship or their government service is indifferent, because wherever they live or serve or invest, they will have the same privileges, advantages, and immunities.

We can think of the technocratic elite as the system administrators of the universal surveillance state, although the particular nation-state for which they are the custodians of surveillance are indifferent. We know that blocs of nation-states freely share their intelligence along elites — for example, within NATO, and more freely yet among the “Five Eyes” of Anglophone intelligence services. Thus while nominally loyal to the interests of a particular nation-state, the technocratic elite are in fact loyal to the international system of nation-states and the vested interests that this system represents. That same anarchic individualism that the procedural rationality of the universal surveillance state seeks to suppress, or, at least, to channel and control, is manifested at a higher order of magnitude among nation-states in the anarchic nation-state system that has been and is becoming institutionalized in international institutions (cf. State Power and Hypocrisy).

The masses can be bought off by the contemporary equivalent of bread and circuses — i.e., food stamps and mass entertainment — they can be be distracted and redirected by a barrage of trivia called “news,” and they can be seduced into passivity by relatively easy working conditions and cheap consumer goods. The middle classes can be bought off by better consumer goods, new luxury cars, and large houses. The more ambitious among the middle classes can be buried under the debt that they acquire in order to acquire the credentials that will secure the social mobility that they desire. The limiting mechanisms of social control assure that there is very little social mobility into or out of the elite class itself, however much social mobility into or out of the middle class, or within the various levels of the middle class, may occur.

In a world of seven billion people, there are only a finite number of Ferraris, Armani suits, and oceanfront mansions; these finite goods are allocated according to a system of privilege intrinsic to the technocratic nation-state. While a member of the middle class may move up in status and wealth and eventually acquire such goods as they may purchase (the best consumer goods, lying beyond the means of most of the middle class, who can afford only better consumer goods beyond the means of the masses), in the big picture these goods are merely decorative, and they may serve to confer status without real power to those who are most deeply invested in the status quo of our society. They have done what is expected of them, and they are rewarded for their loyalty and hard work. They also serve as models for the masses and the less successful middle classes. This is the institutional true believer, i.e., the individual who gives himself or herself to the state, and the state in turn gives to the individuals who have identified their interests with those of the institution in question the rewards due to their station. (I have previously written about such individuals in A Third Temperament.)

It is not difficult to recognize such institutional true believers. Foucault now appears as much a prophet as a philosopher, as he noted that in the change from right of death to power over life, such men are “no longer the rhapsodist of the eternal, but the strategist of life and death.” This is now literally true with the special place that healthcare holds in industrial technological civilization: religion once held out hope of salvation in another world; medicine now holds out hope of salvation in this world. With the PPACA and its individual mandate forcing everyone into the medical-industrial complex, doctors will become the agents of the universal surveillance state. Many medical institutions have already done so, voluntarily and enthusiastically. And this should not surprise us. Being an agent of a powerful entity means access to power, and access to power means privilege. They, too, can reap the material rewards of their special position in society.

Yet in a world of ever more available consumer goods, privilege is increasingly expressed in the form of intangibles. In the information-driven world of industrial-technological civilization, information is power, and access to privileged information is not only restricted to privileged individuals, but the very act of restriction on information creates a privileged class that has access to that information.

Recently I was corresponding with a friend in Tehran, who was telling me about all the internet restrictions in Iran. I asked if the people there accept this with resignation, complain about it, or make excuses for it, and was told that countless excuses are made for these restrictions. We in the west can laugh and be smug about this, except that the situation is little different in western nation-stations. We have seen countless excuses made for the universal warrantless surveillance conducted by the NSA, and shocking vitriol and invective directed at anyone who questions the wisdom of this surveillance regime.

The hysterical response to WikiLeaks disclosures and the Snowden leaks was not about national security, it was about the technocratic elites of the universal surveillance state, who base their status upon privileged access to restricted information, having their status called into question. Security is not an end in itself, but is only a means to an end — the end of social control.

In an op-ed piece on Wikileaks, Google and the NSA: Who’s holding the ‘shit-bag’ now?, Julian Assange recounts what happened in the wake of an attempt by WikiLeaks’ staff to call the State Department directly in order to attempt to speak to Hillary Clinton:

“…WikiLeaks’ ambassador Joseph Farrell, received a call back to discuss the parametres of the call with Hillary, not from the State Department, but from Lisa Shields, the then-girlfriend of Eric Schmidt, who does not formally work for the US State Department. So let’s reprise this situation: The Chairman of Google’s girlfriend was being used as a back channel for Hillary Clinton. This is illustrative. It shows that at this level of US society, as in other corporate states, it is all musical chairs.”

Assange is right: among the technocratic elite, it’s all musical chairs. But Assange was wrong in implying that things are different outside corporate states. It has always been musical chairs among the elites, whether technocratic or corporate or otherwise. The nature of the society or the civilization may shape the nature of the elites, but it does not change the fact of power elites, which is a civilizational invariant.

It is important to keep in mind that, while the technocratic elite of industrial-technological civilization are no more venal than the elites of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, they are also no less venal. Similarly, the technocratic elite of industrial-technological civilization are no more rapacious than the elites of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, but they are also no less rapacious that their predecessors.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Spooks and Skullduggery

21 December 2011

Wednesday

Two news stories today underlined Chinese dedication to the incremental accumulation of intelligence by way of a kind of espionage gradualism that eschews cloak and dagger operations as well as spectacular “crown jewels” kinds of intelligence coups in favor of a broadly-based campaign to collect all that it can collect by whatever means possible. China is well known in the intelligence community for its cultivation of “open source” intelligence, which means that Chinese agents comb through vast amounts of readily and legally available information, sending back whatever is thought to have some value. Given a base population of well over a billion people, one can easily understand the efficiency of this method for the Chinese.

The Chinese are not likely to have a big spy ring caught or deported, after the fashion of Anna Chapman et al., but they sometimes push the limits and go beyond what is strictly open source. When they do so, they rarely do so by way of cash or sexual favors, which are perhaps the most common inducements in Russian and American spy rings, but the Chinese rather appeal to the Chinese ethnicity of well-placed individuals (rather than attempting to establish networks of individuals, which then in turn seek to insinuate themselves into sensitive positions) to induce them to transfer sensitive information and technology to China.

A perfect example of this is the industrial espionage case in which Ke-xue Huang admitted to stealing trade secrets from Dow AgroSciences and Cargill Inc. and sending them to China. Ke-xue Huang is a Chinese national with permanent resident status in the US. Today the BBC reported that Ke-xue Huang was sentenced to seven years in prison in Chinese scientist Huang Kexue jailed for trade theft.

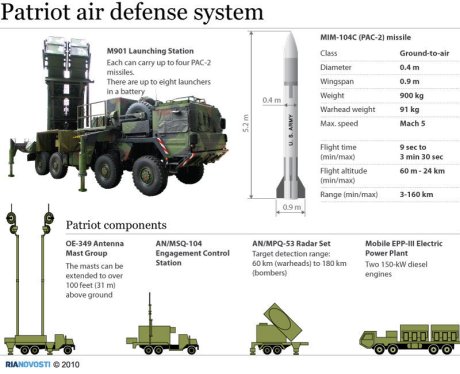

The BBC also reported today the detention of the Ukrainian-crewed, Isle of Man flagged ship M/S Thor Liberty at the Mussalo container terminal at Port of Kotka, Finland, in Finland ‘finds Patriot missiles’ on China-bound ship. Port workers noticed carelessly stored explosives on the ship and did more poking around, which led them to 69 Patriot missiles in crates labeled as “fireworks.” The ship was bound for Shanghai (as well as South Korea), but of course there was no documentation connecting the missiles with a Chinese destination.

One could interpret this shipment of Patriot missiles as an extraordinarily sloppy piece of skullduggery, which would make the Chinese look foolish and incompetent. Are they? I don’t think so. One could also interpret this shipment as a low-risk, low-payoff piece of skullduggery very much in line with known Chinese espionage methodology. Its seizure is without question an embarrassment, but not likely the cause of an international incident. Patriot missiles are widely sold to US allies. The Chinese could probably obtain them in other ways. Perhaps the opportunity presented itself to obtain a cargo ship full of them, and the very marginality of the operation was an attraction for the little attention the ship would attract.

Every nation-state in the world has laws against espionage, yet every nation-state in the world operates espionage networks, and is always on the lookout for espionage networks operating on its own soil. It is very much a cat-and-mouse game. The Chinese prefer to chase lots of small mice with lots of small cats. The US and Russia tend to have a few larger cats chasing a few larger mice. Each method has its advantages and its disadvantages.

A really spectacular piece of skullduggery can have a huge payoff, but if the spy ring is cracked or turned, there can be an equally large payoff in the unintended direction. Espionage is particularly vulnerable to unintended consequences. And when the stakes are high, it is a deadly game, and assets lose their lives. From this perspective, Chinese espionage methodology looks risk averse.

It ought also to be pointed out that spectacular intelligence assets can be wasted, as I attempted to describe in Missed Opportunities: CIA Spies in Iran. If great risks are taken to place high level spies in valuable positions, but the intelligence gleaned from such operations is frittered away on short term advantages, then you have put your assets in a dangerous position on an indefensible pretext.

The coming days will likely reveal more about the M/S Thor Liberty, though it will likely be months or years before the public gets the story, as with the case of the M/V Faina, the story of which only came to light as the result of Wikileaks. So here is one more plug for Wikileaks, Pte Bradley Manning, now in pre-trial hearings, and Julian Assange, soon to be extradited to Sweden. The poor man’s intelligence network — that is to say, the intelligence network open to you and me — is constructed from leaks, blogs, tweets, private correspondence, and any other source we can cultivate. Without this quasi-Chinese open source intelligence network, we would be even more utterly in the dark than we in fact are.

. . . . .

The Finnish site portti.iltalehti.fi has this detailed information on the M/S Thor Liberty:

Name: Thor Liberty

IMO: 9065273

Flag: Isle Of Man (uk)

MMSI: 235218000

Callsign: ZNGT5

Former name(s):

– Cec Liberty (Until 2009 Oct 28)

– White Rhino (Until 2008 Nov 06)

– Cec Liberty (Until 2007 Dec 03)

– Cec Hope (Until 2002 Nov 28)

– Cic Hope (Until 2001 Nov 21)

– Arktis Hope (Until 2000 Jan 04)Administrative Information

Home port: Isle Of Man

Class society: Lloyd´s Shipping Register

Build year: 1994

Builder*: Nordsoevaerftet

Ringkobing, Denmark

Owner: Habro Kongea

Copenhagen, Denmark

Manager: Greenstar Steamship

Haren Ems, GermanyTechnical Data

Vessel type: Cargo

Gross tonnage: 3,810 tons

Summer DWT: 5,392 tons

Length: 97 m

Beam: 16 m

Draught: 5Port history

2011 December 11th, 21:00:06 UTC Kotka

2011 December 6th, 11:00:32 UTC Emden

2011 December 3rd, 09:00:40 UTC Papenburg Germany, probable loading port

. . . . .

Note Added 27 December 2011: Since I wrote the above there have been several news stories claiming that the Patriot missiles were a legitimate shipment of second-hand German missiles that had been purchased on the up-and-up by South Korea, and in fact the M/S Thor Liberty was scheduled to make port in South Korea before heading to Qingdao. Cf. Finland questions Germany-South Korea missile shipment and Germany: Patriot missiles impounded in Finland were legit shipment to South Korea. This is plausible story, but I remain skeptical that it is the whole story or the correct story. If I were the captain of a ship with both missiles and explosives on board, I would want to make a minimal effort to make sure my papers were in order. Since it was the Germans who confirmed the legitimacy of the missile shipment to South Korea, I have to wonder if the Germans routinely ship weapons systems without adequate documentation, and, if they do, how they assure that these weapons systems are off-loaded at the correct port and transferred to the intended purchasers. And, again, if I were the captain of a ship transiting winter seas with both missiles and explosives on board, I would want to made some kind of effort to make certain that the explosives were properly restrained and did not present a danger during the voyage. According to Finnish customs officials, the explosives did pose a danger in high seas.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Web 2.0: An Alternative Vision

31 December 2010

Friday

Whither the Web?

A Warning for the New Year

One of the most disturbing things about dictatorship and political manipulation during the twentieth century was the skill and sophistication that the power-hungry brought to novel forms of mass media. The German experience of Nazism, which ought to be a lesson that no Westerner ever forgets, would have been impossible without the skillful use of mass media for nefarious ends. The newsreel and the radio broadcast were as central to Nazi control as mass party rallies. More recently, the simplified and streamlined genocide in Rwanda (in contrast to the technological sophistication of the Nazi genocide) made extensive use of radio broadcasts to target victims. Newspapers, magazines, radio, film, and television created a new mass media climate, and this media climate was mastered with with surprising rapidity by the most brutal elements of society, making it possible for a violent minorities to seize control of nation-states, to intimidate and terrorize their rivals, and to dictate their ideological fantasies to the masses.

The telecommunications revolution of the twentieth century (getting its start in the nineteenth century with the telegraph and transoceanic cables) seemed to realize its implicit promise in the emergence of the internet in the late twentieth century. I got my first laptop and my first e-mail address in 1996. At this time, the internet was like the Wild West: wide open, competing standards, no consensus on what would happen next. It was a riot of activity and innovation in a newly created world that simply did not exist ten years previously. It was messy and unpredictable, and it was fascinating.

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the still new and still innovative internet began to change even faster as interactive web applications became more common. We now typically refer to this mutation as Web 2.0, and if the initial emergence of the internet seemed to promise universal access and communication without the intervention of the state, Web 2.0 seemed to be an acceleration of this development, with mass collaboration on social networking and information websites. This development suggested a level of democratization that was unprecedented in the history of the world.

But all is not well in the wide, wonderful world of Web 2.0. China has walled its citizens off from the rest of the world by its Great Firewall of China, and the growing market power of China, now the second largest economy in the world, has made the large industries associated with the internet willing to compromise themselves in order to do business with the regime: they receive their thirty pieces of silver, and the people of China are imprisoned by an information network that seems to promise universal and free expression, but which in fact represents only a censored fragment of what is common knowledge elsewhere in the world.

Recent events have demonstrated that the advanced industrialized democracies, which have prided themselves on their openness, and have attributed their social stability and economic success to this same openness, are little better than China when they perceive their interests to be threatened. It has been a shock to me personally to see how quickly and how easily media outlets and internet industries have been willing to abandon WikiLeaks because they made a few powerful people angry. This ought to be a lesson to us all. As long as you discuss film and fashion, download pornography or gamble online, you are no threat to the established order, but if you cross the line into political activity, and you reach a worldwide audience, you will find yourself without friends and without protectors. You may even find yourself with the most powerful nation-state in the world pursuing you, and seeking to charge you with espionage though you are not a citizen, not a resident, none of your activities occurred within the territory of said nation-state, and you are not subject to the laws of that nation-state.

We have come to the point where there is a difference in degree between the political control exercised by the advanced industrialized democracies and one-party states like China, Burma, and North Korea, but there is not a difference in kind. That is to say, we have more freedom of expression and more openness than rogue states and dictatorships, but we don’t have freedom and openness simpliciter.

The handful of people who run the world’s governments are not stupid. They have proved by their deeds that they know how to seize power, how to retain power, and how to use power to their own ends. They will not willingly forgo the opportunity to use the potential power of the internet in order to consolidate their grip on power. It would be contrary to their nature to do so, and it would therefore be foolish of us to expect anything different.

All over the world, among individuals of all races and persuasions, East and West, rich and poor, influential and anonymous, privileged and underprivileged, there are persons who believe that they know better than you know what is in your own best interest. While the poor and anonymous and underprivileged are rarely a direct threat to us because of their lack of resources, they constitute the power base of those who are rich and influential and privileged. Without the Lumpenproletariat of the technological age, those who would arrogate to themselves the status of deciding the fates of others would have no power. Even in nation-states with advanced political and social institutions which seem to have supplanted the ancient institutions of pre-modern societies, we find implicit within the social milieu of our time the client-patron networks that have been the backbone of societies as diverse as the Persian Empire, the Roman Empire, the Mogul Empire, the Spanish Empire, and the British Empire. These client-patron networks connect diverse individuals and social classes into a unified social system in which each serves the interests of the other.

The new telecommunications technologies of the twentieth century seemed to promise the empowerment of individuals; the age of the dictatorial social milieu seemed to be coming to an end. It has been argued, and still is argued, that telephones, photocopiers, fax machines, and other media of “first wave” of the telecommunications revolution, make it impossible to silence the individual who is determined to speak out. But the institutionalized state was not far behind. Telephones can be tapped. Photocopiers can be monitored. Faxes can be intercepted. Typewriters can be licensed. And so it is with the internet. China has shown how even something as large, as amorphous, and as buzzing with activity as the internet can be managed, within limits, and now the Western powers are learning from this police state how it can police its own internet traffic. And the institutionalized industries of the internet, who have refined their techniques of information control in East Asia at the behest of one-party states, can bring their expertise in stifling dissent back to the West.

We all know the mythology of the large computer and internet companies of today: how they began in garages, were run by people who were passionate and enthusiastic about what they were doing, how they were contemptuous of the institutions of polite society, and how they proved the skeptics wrong. Now these companies have grown up. They are no longer housed in garages. They have plush office suites, boards of directors, stock tenders, and a great many people earning high salaries, who, after proving their success to a skeptical world, would not now want to come down in the world, having won their battle for recognition, prestige, and wealth. These industries now have vested interests, and they no more want to upset the status quo than the record industry wanted to stop selling cassettes and CDs. And this is why they cooperate with government authorities.

We need to recognize that the internet is a mass media, and that the collaborative applications of Web 2.0 are the full flowering of a truly mass media in which the masses participate as masses in the production of their own media. It requires but little political imagination to see that the mass media of Web 2.0 could be as quickly and as cleverly manipulated by institutionalized powers as newspapers, magazines, radio, film, and television. Web 2.0 is, in fact, all of these things and more. There are streaming radio broadcasts and endless videos on Youtube and Hulu, and endless media outlets. None of these things are beyond the control of the state.

As against the mindless happy talk that persists in portraying internet technologies as empowering the masses, there is the warning from history — many warnings from history, in fact, but the twentieth century lesson of dictatorships that have consolidated and extended their powers through mass media manipulation is the lesson most germane to our experience today — that tells us that every technological innovation inevitably will be exapted by institutionalized powers to serve their ends.

There are a handful of people today who are not merely talking the talk — which, all too often, is mere “happy talk” about freedom and democracy — but who are walking the walk at great risk of personal sacrifice. Among them we may count Aung San Suu Kyi in Burma, Ai Weiwei and Liu Xiaobo in China, and Julian Assange, wherever he is being held at the moment. While these figures are a diverse lot, and we may admire some even while detesting others, we owe it to ourselves, to the possibility of self-determination for ourselves and for others in the future, to defend them all in whatever capacity we are able to do so. Julian Assange has a rape charge pending against him. Who wants to be associated with a rapist? No one. The institutionalized powers know this, and they play upon it.

The fight for WikiLeaks to make documents public in the Western democracies and the fight for activists like Ai Weiwei and Liu Xiaobo to speak out publicly in China are intimately related. One cannot avoid noticing that these struggles are taking place in the two largest economies in the world at present. Today, these are the fights worth fighting. This is the good fight. It is not a fight of nation-state against nation-state, nor class against class, but of individuals against institutions that seek to regiment the life of the individual for the convenience of those institutions and those who control and benefit from the institutions.

. . . . .

. . . . .

Once more, with feeling…

4 December 2010

Saturday

Clockwise: Hillary Clinton condemned WikiLeaks; Nicolas Sarkozy called WikiLeaks a threat to democracy; Robert Baer bemoaned the leaks in the Financial Times; Julian Assange, founder of WikiLeaks, is on the run from Swedish Police and is wanted by Interpol.

One thing we have learned — or should have learned — from the documents recently made available to the public on WikiLeaks, is the poor quality of our intelligence. Of course, even the best leaks were only classified “SECRET” and we didn’t get any Top Secret goodies, but now we know the sort of thing that is called a secret, and it isn’t very shocking or surprising.

Certainly there were some embarrassing statements not intended for public consumption, but nothing that you wouldn’t find in a moderately free-wheeling memoir written some years after the fact. What strikes me most about these cables is that they are nothing more than you might get than the sort of intelligence produced by Strategic Forecasting. I’ve subscribed to Strategic Forecasting for several years now, and I appreciate the intelligence they offer, and sometimes find their analyses illuminating. But this material definitely has its limits. Similarly, the leaked diplomatic cables have their illuminating moments, but also their limits.

Anyone who is a serious delver (or, if you prefer, anyone who is willing to “drill down”) into open source information can find almost as telling material from a variety of sources. These sources are mostly unknown, certainly not famous (you can’t get candid information from the streets of the world’s cities if you are a celebrity), and not connected to the US diplomatic service, or even connected in any way to the US government. But it is not only US agents who are invited to weddings in Dagestan, or doing business across the border between China and North Korea. And some of them write about the experiences as objectively, as sensitively, and with as much or as more understanding as the State Department.

It has often been said that the western style of intelligence gathering (and hear I am counting the Russians as Westerners) involves clandestine efforts to seize information purposefully kept secret by other political entities. This is the “moon shot” of espionage. In contradistinction, China has been known for its patient, thorough, and methodical collection and survey of open source information (as well as relying upon the loyalty of ethnic Chinese, regardless of citizenship). This WikiLeaks tempest, when we reflect on the nature of our confidential intelligence that has been leaked, gives us an appreciation (or should give us an appreciation) of what can be done with open source intelligence gathering.

We should learn to appreciate open source research because it is a good as “secrets.” But we already knew that the quality of our “secrets” was poor at best. I have written elsewhere that the most interesting thing about intelligence in the last half century or so has been its monumental, catastrophic failures. As a consequence of the fact that we cannot count upon our intelligence, we must expect to be blindsided by history. And once we have been blindsided by history, left to negotiate our way through the ensuing chaos, will we not need all the tools of diplomacy at our command, including secrecy?

In the Financial Times opinion piece by Robert Baer that I discussed in Robert Baer on WikiLeaks, the noted spook contends that with the WikiLeaks revelations, “we risk forgetting the worth of diplomatic ‘back channels’ –- a strictly private way of communicating with the president of the United States.” But there is no reason whatsoever that we should run this risk. On the contrary, we ran the risk of forgetting this when about three million people have access to the caliber of “secrets” revealed by WikiLeaks. And Baer obliquely acknowledged this.

Truly secret secrets, and high level negotiations between heads of states, can be kept secret by being confined to two or three people. In the example of the US, this might be the President, the Secretary of State, and a negotiator, etc. And this is, of course, what Kissinger did in his famous shuttle diplomacy in facilitating the end of the Yom Kippur War. Baer no doubt had this in mind when he wrote that the president could, “assemble half a dozen special representatives to ferry messages back and forth to the White House… Any cables generated from this back channel should only be archived in the White House. Better yet, they should not be put down on paper.” Diplomatic cables never even aspired to replacing this kind of high level diplomacy, and it was never expected that they should.

Nothing about shuttle diplomacy has been or will be compromised by WikiLeaks. Nothing that heads of state say to each other in closed rooms has been or will be compromised by WikiLeaks. The only thing that has been compromised by WikiLeaks is the self-importance of those entitled to peruse dubious secrets.

When we examine the rationale for continued secrecy advanced by the critics of WikiLeaks, we find the sotto voce implication is that the people, such as they are, cannot be trusted to to make sound political decisions on the basis of honest and open information. The clear implication is that all governments make certain statements for the consumption of the public, because the public must be told certain things to keep them complacent, but that the real policy making goes on in secret behind closed doors, and these secrets must be kept both for the good of the public and the good of the state.

This brings us to another lesson that should be learned from the furor over the WikiLeaks publication of US diplomatic cables: if the people today cannot be trusted to make sound decisions for themselves, but require their betters to do the work for them, what kind of education would be needed to bring the citizenry up to the level of being able to make wise, reflective, and carefully considered judgments on matters of great difficulty and complexity? I invite the reader to consider this question as a thought experiment, and as soon as we begin to think in these terms we can immediately seen the glaring if not embarrassing inadequacy of our educational system.

For all the talk of education, and all the emphasis on credentials in the advanced industrialized world, most people are frankly not prepared for citizenship. Think of the basic economic knowledge required to understand that protectionism doesn’t help and only makes everyone poorer, even if that impoverishment is subtle and hidden in a statistical tick — it is obvious that even this basic knowledge of lacking, as there is often wide support for protectionism and other populist measures. Indeed, even among our betters who arrogate secrets to themselves, there is largely no understanding of such issues.

Now think beyond the fallacies of economies indulged by the ballot box, and imagine trying to educate a citizenry so that it could make intelligent decisions about complex issues in diplomacy, without being reactive, without saying, “We’ll just nuke ’em,” without deliberating past the point when effective action is possible, without withdrawing troops as soon as a few have been killed in an engagement, and without revealing to our adversaries the intrinsic weaknesses of an open and democratic society. As depressing as this may sound because of the impossibility of it, I would sooner trust myself and my fate to such an open process, and to the attempt to educate the citizenry to a level of adequate diplomatic sophistication, that to entrust anyone’s fate or future to the deliberations of experts or professionals or spooks or State Department hacks. It was the experts and the professionals, after all, who presided over our catastrophic intelligence failures. We do better to trust in our ignorance than in seeming knowledge — precisely the sort of thing that Socrates sought to expose, and got himself killed for doing so.

. . . . .

. . . . .

Robert Baer on Wikileaks

2 December 2010

Thursday

Prominent former spook Robert Baer has written a piece for the Financial Times on WikiLeaks — Secrecy makes the world go round — in which he is highly critical of the leaking of the diplomatic cables currently being posted to WikiLeaks. He writes that, “the damage to American credibility and diplomacy is incalculable.” I disagree, and I will try to explain why I disagree.

Make no mistake, Baer is a clever man. I have seen him interviewed on television, and I have read one of his books, See No Evil, about his time in the CIA. He obviously has both an astonishing depth of knowledge and depth of experience, and has seen more of the world — and more of how the world works — than most people will see in a lifetime. But depth of knowledge and depth of experience are not always enough. His article on WikiLeaks for the Financial Times is, I am sorry to say, fundamentally dishonest.

Baer’s opinion piece is dishonest because he frames what he sees as the “eclipsing of American power” and the damage to American diplomatic credibility, as being attended by, “Wikileaks’ admirers’ trumpeting of the virtues of transparency.” And “the populist diplomacy that WikiLeaks demands” is, for this former dealer in secrets, an anathema. This spins the story so that we are to believe that there are a small number of trustworthy people who have access to secrets, that their ability to do their job has been compromised by these secrets being revealed to the public, and that there has been widespread acclaim for this act of revelation that brought the secrets to light. The last of these three claims is manifestly false. Almost every government in the world has condemned the leak in the strongest terms. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange is a man on the run from the law, on charges he claims were trumped up. Ecuador, who initially seemed to offer sanctuary to Julian Assange has since backtracked on the offer. And, in the meantime, the WikiLeaks site has come under attack — which is to say that it has been attacked in a campaign of electronic warfare. This is not a triumphant organization, but one under attack.

Despite his snide comment on “populist diplomacy,” Baer himself has recently taken a populist line, even suggesting in one interview that the 11 September 2001 attacks may have had “an aspect” of an inside job to it, thus putting himself in the company of “9/11 truthers” (although he did later put himself on the record as denying that 11 September was an inside job). Moreover, Baer has recently reviewed the John Perkins book Hoodwinked on Amazon.com, writing, “I wasn’t twenty pages into Hoodwinked when I realized Perkins nailed it. What got us into the mess we’re in today, the worst recession since the Great Depression, is the same grotesque capitalism cum corruption we shoved down the throat of the Third World since the end of World War II.” These two public statements are enough for me to conclude that Baer has fatally compromised himself, and his judgment is not to be trusted.

The more interesting thing here, and interesting even though very predictable, is the pattern of admiration and condemnation that has emerged. People in positions of privilege and power, people like Hillary Clinton and Robert Baer, have condemned the leak. In other words, people with top secret clearances, the people who would get to read this diplomatic cable traffic anyway, think that it is a terrible thing that others should have access to the information that they take for granted. On the other hand, those who are dealt out of the doings of the security-cleared and the well-connected, those who are not within the charmed circles of diplomacy, those who do not have seats at the Captain’s Table, are generally in favor of the leaks. As I said, this is interesting, but not at all surprising.

If Baer is right in his Amazon.com review of the Perkins book, in which he criticized political, economic, and media insiders for the handling of the financial crisis, why should we continue to trust these insiders — the people with security clearances to read confidential government information — with this sensitive diplomatic information? If the small number of people who have “legitimate” access to these secrets have gotten us into such a mess, why should we continue to favor them with this secrecy? Indeed, we should not.

In any case, Baer predicts what I wrote about a couple of days ago in Honesty as a Strategic Shock: that “secret” diplomatic information will be subject to further controls in the future, and, as I noted, this will have the effect of further marginalizing the insiders who are continually painting themselves into a privileged but progressively smaller corner.

. . . . .

. . . . .