The Pastoralist Challenge to Agriculturalism

13 April 2014

Sunday

The great age of horse nomads

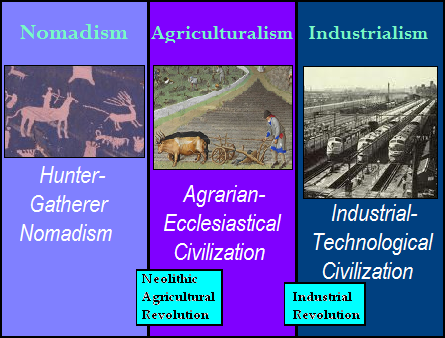

In discussions of the large-scale historical structure of civilization I often have recourse to a tripartite distinction between pre-civilized nomadic foragers, settled agriculturalism (which I also call agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization), and settled industrialism (which I usually call industrial-technological civilization). I did not originate this tripartite distinction, and I cannot remember where I first encountered an exposition of human history in these terms, but this decomposition of human history serves the purposes of large-scale historiography — call it the “big picture” if you like, or Big History — so I continue to employ it.

In this model of the descent with modification of civilization, agriculturalism proved to be so successful a way of life that it eventually (after a period of several thousand years of transition) displaced nomadic hunter-gatherers, who became a minority and a marginalized population while agriculturalism came to literally dominate the landscape. Agriculturalism in turn has been and is being supplanted by industrialism, which holds such potential for economic and military expansion that no agricultural people can hope to stand against an industrialized people. As a result, agriculturalism in its turn is becoming a minority and marginalized activity, while the world continues its industrialization — a process which has been underway a little more than two hundred years (or, say, five hundred years, if we date from the scientific revolution that made this new civilization possible).

Agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization persisted for more than ten thousand years, but these ten thousand or more years were in no sense static and unchanging. Agricultural civilization, especially pure agriculturalism, is an intensely local form of civilization, and as it is subject to the variability of local climatic conditions, it is subject to periodic famine. Thus agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization repeatedly fell into dark ages, sometimes triggered by climatic events. Socioeconomic stress is often manifested in armed conflict, so these low points in the history of civilization, besides being wracked by famine and pandemics, were also frequently made all the more miserable by pervasive, persistent violence. But agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization not only rebounded from its dark ages, but also seemed to gain in strength and extent, so that subsequent dark ages were shorter and less severe (thus perhaps making civilization itself an example of what Nassim Taleb calls antifragility).

What is missing in this narrative is, that prior to the industrial revolution, settled agricultural civilization underwent a great challenge — a challenge to its socioeconomic institutions almost as wrenching as that of the industrial revolution, although this challenge came in a very different form than machines. It came in the form of horses, that is to say, mounted horse warriors from the steppes of Eurasia, who brutally plundered the vast inland empires of the medieval and early modern periods as the Vikings had earlier brutally plundered the coastal areas of early medieval Europe. History mostly remembers these peoples as barbarians, but that is because histories are mostly written by settled agricultural peoples. The miseries and sufferings of settled agricultural peoples at the hands of these barbarians was at the same time the great age of nomadic pastoralists, when the latter came close to seizing the momentum of history.

A distinct form of civilization

As western civilization stumbled with the collapse of Roman power in the west, and was repeatedly prevented from full recovery due to famine, plague, and violence, a very different form of socioeconomic organization was consolidated in the steppes of Central Asia: nomadic horse warriors. Whether one wishes to call this a distinct form of civilization — say, nomadic-pastoralist civilization — or a non-civilization, if civilization is understood to consist, by definition, of settled peoples, the form of social organization that emerged in Eurasia represented by nomadic pastoralists was both distinct and unique. It was also, for a time, highly successful, especially in armed conflict.

The nomadic pastoralists were not without precedent. In my post The Nature of Viking Power Projection, I wrote, “Ships came out of Scandinavia like horses came out of Mongolia.” I have elsewhere argued that Viking civilization represented a unique form of civilization not often recognized in histories of civilization. Here I would like to argue that nomadic pastoralists also represent a unique form of civilization; like the Vikings, this civilization is not based on settlement, but unlike the Vikings, it is a way of life based on the land and not the sea.

Nomadic pastoralists often adopt a semi-settled way of life called transhumance, which involves an annual migration between winter and summer pastures, ascending to higher elevations for summer pasture and descending into the valleys for winter pasture. Thus they may be considered to exemplify a transitional way of life between pure nomadism and settled life. But this is not the only difference between horse nomads and foragers. One important feature of life that distinguishes nomadic pastoralists from nomadic foragers is that the economy of the former is based on domesticated animals (generally, the horse) while that of the latter involves following herds of non-domesticated animals (generally, reindeer). The nomadic pastoralist exercises a far greater control over the landscape in which he makes his life, and a much greater control over the animals upon which he is dependent. It is in this sense that the nomadic pastoralists deserve to be called a civilization, because the relationship between these peoples and their horses was as central to their way of life as the relationship between settled peoples and their crops — only it was a different relationship of dependence.

An unparalleled weapons system

The military accomplishment of the Mongols and the other horse nomads of Eurasia was remarkable. To train, equip, and maintain a fighting force capable of defeating any other force in the world would be a challenge even for the greatest land empires, but that this was accomplished without the established infrastructure of a settled civilization producing agricultural surpluses, which was what equipped and maintained the armies of settled agricultural peoples. John Keegan, famous for his The Face of Battle, also wrote A History of Warfare, in which he includes much interesting material on what he calls the “horse peoples” (especially Chapter 3, “Flesh”).

The most successful of the nomadic pastoralists from the Asian steppe were unquestionably the Mongols, sometimes called the Devil’s Horsemen. From the historical accounts of Mongol depredations upon Europe and the European periphery, the the attacks of the Mongols sound like a natural disaster, like a plague of locusts, but the Mongols were in fact highly disciplined and employed battlefield tactics that the European armies of the period could not effectively counter for hundreds of years. This is an important point, and it is what accounts for the Mongols’ success: although predicated upon a profoundly different socioeconomic organization than that of the agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization of Europe and the European periphery, the Mongols created a land-based fighting force that for several centuries out-matched every military competitor in Eurasia.

The Mongols perfected a weapons system of mobile fire, which latter I have argued has always been the most potent instruments of warfare in any age. If the Mongols had achieved a level of political organization commensurate with its military organization, their socioeconomic system might have ultimately triumphed in Eurasia, and agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization would have been supplanted by nomadic-pastoralist civilization instead of later being supplanted by industrial-technological civilization.

A uniquely brutal conquest

The Mongols militarily defeated both China and Russia, two of the largest land empires on the planet, and would have permanently subjugated these peoples had they the political structures capable of administering the territories they conquered. Instead of the brutality of horsemen, the Chinese were ultimately subject to the brutality of Chinese emperors and the Russians to the brutalities of their Tsars, which despite being horrific, was less horrific than the depredations of horse nomads.

The conquests of the Mongols were destructive beyond the level of destruction typical of that inflicted by the armies of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, and this brutality possibly reached its peak with the depredations of Tamerlane, also called Timur the Lame, who is estimated to have been responsible for the death of about five percent of total global population of the time (the Wikipedia article cites two sources for this claim). In this sense, Tamerlane had much in common with a natural disaster (I noted above the the depredations of horse nomads were often treated like natural disasters by the settled civilizations who suffered from them), as such mortality levels are usually confined to pandemics.

It may have been this brutality and destruction as much as the lack of higher order political organization that ultimately limited the ability of pastoral nomads to rule the peoples they defeated. Notorious leaders of horse nomads such as Attila the Hun, Ghengiz Khan, and Tamerlane seemed to be blind to the most basic forms of enlightened self-interest, as they could have extended their own rule, and had more wealth to plunder, if they have been less destructive in their conquests. This is part of the reason that the peoples that they led are commonly called barbarians, and their way of life is denied the honorific of being called a civilization.

The end of horse nomads as an historical force

If we think of the Turkic peoples of Central Asia as the inheritors of the traditions of horse nomads, the period of the pastoralist challenge to settled agriculturalism continues into the early modern period of European history, up to the two sieges of Vienna, Siege of Vienna in 1529 by the forces of Suleiman the Magnificent, and the Battle of Vienna in 1683, when in both cases Turkish forces sought to take Vienna and were repulsed.

Western history remembers the turning back of the Turks at the Gates of Vienna as the turning point in the depredations of the Turkish Ottomans on Europe. In the following years, the Turks would be pushed back further, and lands would be recovered for Europe from the Turks. But we might also remember this as the last rally of the tradition of conquest that began with the horse nomads of Eurasia. By this time, the Turks had transformed themselves into an empire — the Ottoman Empire — and had adopted the ways of settled peoples. At this point, horse nomads dropped out of history and ceased to be a force shaping civilization.

The future of nomadic pastoralism

In several posts — Three Futures, Pastoralization, and The Argument for Pastoralization, inter alia — I formulated a kind of pastoralism that could define a future pathway of development for human civilization (note that “development” does not here mean “progress”). If this idea of a future for pastoralism is integrated with the realization I have attempted to describe above — viz. that nomadic pastoralism was the greatest challenge to settled agricultural civilization until industrialization — it is easy to see the possibility of a neo-pastoralist future in which industrial-technological civilization itself is challenged by technologically sophisticated pastoral nomads.

While this scenario of technologically sophisticated nomads sounds more like a script for a science fiction film than a likely scenario for the future, it describes possible forms of existential risk, such as permanent stagnation and flawed realization — the former if such a development took us below the level of technological progress necessary to maintain the momentum of industrial-technological civilization, and the latter if this technological progress continues but issues in a society (or, more likely, two or more distinct societies in conflict, i.e., settled and nomadic) that channels this progress into a new dark age, made the more protracted by the lights of a perverted science.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Conceptualization of Existential Risk

27 July 2013

Saturday

Ninth in a Series on Existential Risk:

How we understand what exactly is at risk.

In my last post in this series on existential risk, Existential Risk and Existential Opportunity, I wrote this:

How we understand existential risk, then, affects what we understand to be a risk and what we understand to be a reward.

It is possible to clarify this claim, or at least to lay out in greater detail the conceptualization of existential risk, and it is worthwhile to pursue such a clarification.

We cannot identify risk-taking behavior or risk averse behavior unless we can identify instances of risk. Any given individual is likely to identify risks differently than any other individual, and the greater the difference between any two given individuals, the greater the difference is likely to be in their identification of risks. Similarly, a given community or society will be likely to identify risks differently than any other given community or society, and the greater the differences between two given communities, the greater the difference is likely to be between the existential risks identified by the two communities.

This difference in the assessment of risk can at least in part be put to the role of knowledge in determining the distinction between prediction, risk, and uncertainty, as discussed in Existential Risk and Existential Uncertainty and Addendum on Existential Risk and Existential Uncertainty: distinct individuals, communities, societies, and indeed civilizations are in possession not only of distinct knowledge, but also of distinct kinds of knowledge. The distinct epistemic profiles of different societies results in distinct understandings of existential risk.

Consider, for example, the kind of knowledge that is widespread in agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization in contradistinction to industrial-technological civilization: in the former, many people know the intimate details of farming, but few are literate; in the latter, many are literate, but few know how to farm. The macro-historical division of civilization in which a given population is to be found profoundly shapes the epistemic profile of the individuals and communities that fall within a given macro-historical division.

Moreover, knowledge is integral with ideological, religious and philosophical ideas and assumptions that provide the foundation of knowledge within a given macro-historical division of civilization. The intellectual foundations of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization (something I explicitly discussed in Addendum on the Agrarian-Ecclesiastical Thesis) differ profoundly from the intellectual foundations of industrial-technological civilization.

Differences in knowledge and differences in the conditions of the possibility of knowledge among distinct individuals and civilizations mean that the boundaries between prediction, risk, and uncertainty are differently constructed. In agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, the religious ideology that lies at the foundation of all knowledge gives certainty (and therefore predictability) to things not seen, while consigning all of this world to an unpredictable (therefore uncertain) vale of tears in which any community might find itself facing starvation as the result of a bad harvest. The naturalistic philosophical foundations of knowledge in industrial-technological civilization have stripped away all certainty in regard to things not seen, but by systematically expanding knowledge has greatly reduced uncertainty in this world and converted many certainties into risks and some risks into certain predictions.

Differences in knowledge can also partly explain differences in risk perception among individuals: the greater one’s knowledge, the more one faces calculable risks rather than uncertainties, and predictable consequences rather than risks. Moreover, the kind of knowledge one possesses will govern the kind of risk one perceives and the kind of predictions that one can make with a degree of confidence in the outcome.

While there is much that can be explained between differences in knowledge, and differences between kinds of knowledge (a literary scholar will be certain of different epistemic claims than a biologist), there is also much that cannot be explained by knowledge, and these differences in risk perception are the most fraught and problematic, because they are due to moral and ethical differences between individuals, between communities, and between civilizations.

One might well ask — Who would possibly object to preventing human extinction? There are many interesting moral questions hidden within this apparently obvious question. Can we agree on what constitutes human viability in the long term? Can we agree on what is human? Would some successor species to humanity count as human, and therefore an extension of human viability, or must human viability be attached to a particular idea of the homo sapiens genome frozen in time in its present form? And we must also keep in mind that many today view human actions as being so egregious that the world would be better off without us, and such persons, even if in the minority, might well affirm that human extinction would be a good thing.

Let us consider, for a moment, a couple of Nick Bostrom’s formulations of existential risk:

An existential risk is one that threatens the premature

extinction of Earth-originating intelligent life or the permanent and drastic destruction of its potential for desirable future development.

…and again…

…an existential risk is one that threatens to cause the extinction of Earth-originating intelligent life or the permanent and drastic failure of that life to realise its potential for desirable development. In other words, an existential risk jeopardises the entire future of humankind.

Existential Risk Prevention as Global Priority, Nick Bostrom, University of Oxford, Global Policy (2013) 4:1, 2013, University of Durham and John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

What exactly would constitute the “drastic failure of that life to realise its potential for desirable development”? What exactly is permanent stagnation? Flawed realization? Subsequent ruination? What is human potential? Does it include transhumanism?

For some, the very idea of transhumanism is a moral horror, and a paradigm case of flawed realization. For others, transhumanism is a necessary condition of the full realization of human potential. Thus one might imagine an exciting human future of interstellar exploration and expanding knowledge of the world, and understand this to be an instance of permanent stagnation because human beings do not augment themselves and become something more or something different than we are today. And, honestly, such a scenario does involve an essentially stagnant conception of humanity. Another might imagine a future of continual human augmentation and experimentation, but more or less populated by beings — however advanced — who engage in essentially the same pursuits as those we pursue today, so that while the concept of humanity has not remained stagnant, the pursuits of humanity are essentially mired in permanent stagnation.

Similar considerations hold for civilization as hold for individuals: there are vastly different conceptions of what constitutes a viable civilization and of what constitutes the good for civilization. Future forms of civilization that depart too far from the Good may be characterized as instances of flawed realization, while future forms of civilization that don’t depart at all from contemporary civilization may be characterized as instances of permanent stagnation. The extinction of earth-originating intelligent life, or the subsequent ruination of our civilization, may seem more straight-forward, but what constitutes earth-originating intelligent life is vulnerable to the questions above about human successor species, and subsequent ruination may be judged by some to be preferable to the present trajectory of civilization continuing.

Sometimes these moral differences among peoples are exemplified in distinct civilizations. The kind of existential risks recognized within agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization are profoundly different from the kind of existential risks now being recognized by industrial-technological civilization. We can see earlier conceptions of existential risk as deviant, limited, or flawed as compared to those conceptions made possible by the role of science within our civilization, but we should also realize that, if we could revive representatives of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization and give them a tour of our world today, they would certainly recognize features of our world of which we are most proud as instances of flawed realization (once we had explained to them what “flawed realization” means). For a further investigation of this idea I strongly recommend that the reader peruse Reinhart Koselleck’s Future’s Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time.

It would be well worth the effort to pursue possible quantitative measures of human extinction, permanent stagnation, flawed realization, and subsequent realization, but if we do so we must do so in the full knowledge that this is as much a moral and philosophical inquiry as it would be a scientific and theoretical inquiry; we cannot separate the desirability of future outcomes from the evaluative nature of our desires.

Like the sailors on the Pequod who each look into the gold doubloon nailed to the mast and see themselves and their personal concerns within, just so when we look into the mirror that is the future, we see our own hopes and fears, notwithstanding the fact that, when the future arrives, our concerns will be long washed away by the passage of time, replaced by the hopes and fears of future men and women (or the successors of men and women).

. . . . .

. . . . .

Existential Risk: The Philosophy of Human Survival

1. Moral Imperatives Posed by Existential Risk

2. Existential Risk and Existential Uncertainty

3. Addendum on Existential Risk and Existential Uncertainty

4. Existential Risk and the Death Event

6. What is an existential philosophy?

7. An Alternative Formulation of Existential Risk

8. Existential Risk and Existential Opportunity

9. Conceptualization of Existential Risk

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Addendum on the Agrarian-Ecclesiastical Thesis

20 June 2013

Thursday

The Classical Greek Intellectual Foundations

of Agrarian-Ecclesiastical Civilization

One of Voltaire’s most famous witticisms was that the Holy Roman Empire was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. Such contradictions abound history; as Barbara Tuchman noted, we should expect them rather than be offended by them: “Contradictions… are part of life, not merely a matter of conflicting evidence. I would ask the reader to expect contradictions, not uniformity.” (I just happened to notice today that Michael Shermer quotes this passage in a Youtube video.) In this spirit of historical contradiction it could be observed that the intellectual framework of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization was neither agrarian nor ecclesiastical, but rather reflected the high point of Greek civilization in classical antiquity.

The intellectual space of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization — the paradigm if you prefer Kuhnian language, or the epistēmē if you prefer the terminology of Foucault — was the result of what we might call the “world-builders” of classical antiquity, of them I would like to call attention to three: Aristotle, Euclid, and Ptolemy.

Aristotle, Euclid, and Ptolemy were the architects of the “closed world” that Alexander Koyré famously contrasted to the infinite universe that was to emerge (slowly, gradually, and at times painfully, as Koyré would demonstrate in detail) from the scientific revolution as played out in the work of Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, and many others (the architects of the infinite universe):

The infinite cannot be traversed, argued Aristotle; now the stars turn around, therefore… But the stars do not turn around; they stand still, therefore… It is thus not surprising that in a rather short time after Copernicus some bold minds made the step that Copernicus refused to make, and asserted that the celestial sphere, that is the sphere of the fixed stars of Copernican astronomy, does not exist, and that the starry heavens, in which the stars are placed at different distances from the earth, “extendeth itself infinitely up.”

Alexander Koyré, From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe, Baltimore, Md.: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1957, p. 35

Aristotle was the comprehensive philosopher who not only had respect for empirical observation (something Plato consistently devalued) but also formulated a system of deductive logic that made it possible for him to connect empirical observations together into a theoretical structure with great explanatory power. Aristotle, then, did not deal with isolated facts, but with theories. Each new fact, each new observation, can in this way be fit within the overall structure of a theory which in Aristotle extends from the summum genus on top to the inferior species on the bottom. There is a place for everything and everything is in its place. The much later conception of a “great chain of being” — a central idea to later agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization — has its origins in the Aristotelian construct.

Euclid and Ptolemy, while comprehensive each within their own disciplines, were nowhere near as comprehensive as Aristotle; it was Aristotle’s philosophy that was the system of the world to which Euclid and Ptolemy contributed. Even though Aristotle distinguished many sciences later recognized as independent intellectual disciplines, with only two exceptions none of these sciences came to be systematically developed in antiquity (except perhaps for Aristotle’s own research in biology). Mathematics and astronomy were the two sciences that were systematically developed in antiquity as sciences recognizable as such, and still recognizable today as sciences.

While later thought, especially medieval thought, made much of the theory of the syllogism found in Aristotle’s Prior Analytics, Aristotle’s theory of science in the Posterior Analytics received much less attention. It was, nevertheless, the theoretical basis of Euclid’s systematic exposition of geometry on the basis of first principles. Euclid brought Aristotle’s world-building and logical rigor into mathematics, and wrote a book on geometry that was used as a textbook well into the twentieth century. We can today read ancient Greek mathematicians as contemporaries, and we can learn something from them; we can similarly read Ptolemy’s treatise on astronomy, the Almagest, as a serious work of astronomy, though we would have less to learn from it than from ancient mathematics.

Aristotle, Euclid, and Ptolemy date (roughly) from what Jaspers called the Axial Age; while peoples elsewhere in the world of maturing agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization were creating religions, the Greeks were creating philosophy of science, and this proved to be a lasting contribution. This was the axialization of Western civilization during the period of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization.

Aristotle provided the philosophical foundations for the thought of later Western civilization up until the scientific revolution, and even after modern science began to change the world, Aristotle’s influence continued to echo in the work of later scientists. Even up into the early modern period, when we see the first signs of modern science taking shape in Galileo’s work on physics and cosmology, scientists were still writing their treatises in the Euclidean manner. Galileo’s early works on motion and mechanics are almost scholastic in tone, but are not as well remembered as his Sidereal Messenger or Dialogues Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. Even Newton’s Principia is laid out more geometrico.

The emergence of industrial-technological civilization from agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization was a process that began with the scientific revolution and continues to this day as the consequences of the industrial revolution continue to unfold, continuing the change the world in which we live. The transitional periods between macro-historical periods — which I have called macro-historical revolutions — are themselves periods of hundreds of years in duration. In fact, the first such macro-historical revolution, which inaugurated the macro-historical division of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, may have been a transition measurable in thousands of years.

In my immediately previous post, The Agrarian-Ecclesiastical Thesis, I suggested that, given the counter-market, counter-developmental mechanisms institutionalized in agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, that its failure is to allow a revolution to take place. The long history of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization — which might be stretched to as much as 15,000 years, depending upon when we date the first domestication of crops and the first settled, quasi-urban villages enabled by domesticated agriculture — witnessed many revolutions, all of which failed except for the last, which issued in the catastrophic collapse of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization and the emergence of industrial-technological civilization.

That I have called contemporary civilization “industrial-technological civlization” and the civilization the preceded it “agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization,” and given that the latter so closely conforms to the distinction between economic infrastructure and ideological superstructure, I am trying to make a point about the overall structure of civilizations, even civilizations that inhabit distinct macro-historical divisions?

The source of Marx’s distinction between economic infrastructure (or economic base) and ideological superstructure is to be found in his A Contribution to The Critique of Political Economy. It is worth revisiting Marx’s formulation. The crucial passage is as follows:

In the social production which men carry on they enter Into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will, these relations of production correspond to a definite stage of development of their material powers of production. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society — the real foundation, on which rise legal and political superstructures and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production in material life determines the general character of social, political, and spiritual processes of life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness.

Marx, Karl, A Contribution to The Critique of Political Economy, translated from the Second German Edition by N. I. Stone, Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1911, Author’s Preface, pp. 11-12

Marx’s formulation is a straight-forward social implementation of a materialist theory of the relation of mind to body, so that we can say at least that Marx was a consistent materialist. Marx’s consistent materialism yields consistent results in the analysis of societies, which in some instances seems to be highly successful and offers us some insight. But not always. No schema can be quite true when stretched to fit every possible instance, and this is true of Marx’s consistent materialism. It collapses when confronted by societies in which there is no distinction between economics and ideology (each of these terms broadly construed).

It would be an interesting intellectual exercise to formulate a binomial nomenclature of civilizations characterizing each in terms of its economic infrastructure and ideological superstructure, but this is too schematic to the quite true. One point I have tried to argue several times (but for which I still lack a definitive formulation) is that distinct civilizations are not distinct implementations of one and the same idea of civilization, but rather distinct civilizations embody distinct ideas as to the nature and aims of civilization. So while “agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization” nicely fits the economic infrastructure/ideological superstructure model, “industrial-tecnnological civilization” does not fit as nicely. While there is a sense in which technology has become an ideology, it is in no sense an ideological superstructure in the same way that institutionalized religion served as the ideological superstructure of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Agrarian-Ecclesiastical Thesis

18 June 2013

Tuesday

Ten Thousand Years of Civilization

From the Agricultural Revolution to the Industrial Revolution

I have adopted the term “industrial-technological civilization” to refer to the civilization that we now have, and I have argued that this civilization can be defined in terms of a unique thesis, the industrial-technological thesis, as well as its implied contrary, industrial-technological disruption, which disruption ensues when the mechanisms of industrial-technological civilization go awry.

Industrial-technological civilization was preceded by agricultural civilization. Like industrial-technological civilization, agricultural civilization is multifaceted and represents a robust macro-historical division between hunter-gather nomadism, which precedes it, and industrial-technological civilization, which follows it. Agricultural Civilization is the “middle ages” of macro-historical periodization, coming between the long epoch of hunter-gatherer nomadism (from the emergence of homo sapiens to the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution) and the youthful energy of industrial-technological civilization (from the industrial revolution to the present day).

I have earlier attempted to characterize the nature of agricultural civilization in many posts, including the following:

Recently I have realized that as our civilization can be characterized as “industrial-technological” to bring out the main features of the age, we might similarly identify the agricultural civilization that preceded our civilization as “agrarian-ecclesiastical” civilization. This hyphenated form brings out the main features of the age: both the agriculturalism of the economic structure and the ecclesiastical form of society that maintained the agricultural economy in trans-generational equilibrium (that is to say, the ideological superstructure).

The distinctive differentia of agrarian civilization is institutionalized religion, just as the distinctive differentia of industrial civilization is technological change driven by science. This does not mean that technology is the religion of the industrial age, or that religion was the surrogate “technology” of agricultural civilization. What it means is that fundamentally distinct forms of civilization are based on fundamentally distinct ideas. This is an idea that I attempted to explore some time ago in The Incommensurability of Civilizations and Addendum on Incommensurable Civilizations.

Institutionalized religion — from the worship of a living god in early agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization (as in Egyptian and Mayan civilization, for example) to the elaborately structured monotheistic religions of the late medieval and early modern period — is uniquely suited to the social demands of a risk-averse agrarian economy that was entirely innocent of growth and progress, but was exclusively concerned with stability and continuity. This focus on stability and continuity — eternal verities of society mirroring the eternal verities of the spiritual realities posited by institutionalized religion — meant an economy structured to provide sufficiency for a traditional way of life, but not sufficient for economic growth or social mobility. What was wanted was not incremental improvement in the way of life, but eternal perfection — heaven on earth.

Agrarian-Ecclesiastical civilization is predicated upon trans-generational equilibrium no less than industrial-technological civilization is predicated upon trans-generalization disequilibrium. To this end, social and economic structures embodied counter-market mechanisms — economic checks and balances that maintained the economic status quo to the greatest extent possible. Social change was also systematically hamstrung. Given this commitment of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization to stability, continuity, and permanence, the catastrophic failure of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization is to allow a revolution to take place — any revolution, whether commercial, scientific, social, or economic. Peasant rebellions have occurred with some regularity in agrarian-ecclesiastical civilizations, but these rebellions have a ritualistic character that distinguishes from them the revolutions of industrial-technological civilization.

When the overall structure of the economy, despite its mechanism to slow and stifle unwelcome developments nevertheless resulted in change, there were uprisings from below, popular revolts that sought to slow and stifle these unwelcome developments. Almost all peasant rebellions in the European middle ages were conservative rebellions, in which the motivation was to restore the status quo ante. Marxist historians of the recent decades have reviewed the record of repeated peasant revolts in the middle ages — and there were many, most prominent among them being Wat Tyler’s Rebellion of 1381 and the Great Peasants’ Revolt of 1525 — and drawn conclusions about a nascent stirring of class consciousness among the agricultural proletariat, but these peasant rebellions never questioned the structure of authority. Indeed, peasant rebellions often appealed to the political trope of “good king, bad advisers,” and believed that if they could only get to the king to make their grievances known, that all would be put right.

In agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization we find capitalism without a free market — carefully channeled within traditional guild structures that limited entry into the professions, limited competition, and maintained the professions and the trades as traditional modes of life no less than the traditional lifeways of peasants and nobility. The legal infrastructure of capitalism without markets, guilds and monopolies, constrain and restrict trade exclusively within ideologically-approved channels. We can compare this systematic limitative structuring of the economy with Erwin Panofsky’s famous thesis in Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism. In this famous study, Panofsky argued that the medieval mind expected to see its ideas explicitly manifested, as we see in the argumentative structure of scholastic philosophy and the physical structure of gothic architecture, with its ribbed vaults and flying buttresses. Panofsky’s thesis could be extended to the legal institutions of the economy which made social position similarly explicit through mechanisms such as sumptuary laws. The elaborate legal codes that enforced the commercial structures of guilds and monopolies can also be seen as exemplifying this thesis.

Later in the development of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, mercantilism was essentially finitistic capitalism, and as such represents the survival of the finitistic assumptions of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization into nascent modernism — though modernism not yet far enough advanced to have crossed the threshold of industrialization and therefore falling short of the macro-historical revolution that defines the advent of industrial-technological civilization.

In an economic environment in which there is no steady expansion (and therefore no inflation built into market mechanisms) in the currency, in which currency (in so far as it was used, i.e., rarely) was tied to some commodity (gold or silver or real estate), and in which no systematic expansion of industry or exploitation of resources occurred, the finitistic, steady-state, zero sum assumptions of mercantilism were true, even if they are no longer true today, in the context of industrial-technological civilization.

Agrarian-ecclesiastical civilizations built on the presumption of non-development aimed not at progress but at perfection. Perfection is a finite good, a finite ideal; once realized, nothing remains to be done. Thus perfection as a social goal embodies something like Comte de Maistre’s finitistic political theory. Contemporary civilization, at least since the industrial revolution — i.e., industrial-technological civilization — has often been criticized for its faith in progress, but this is not quite the naïve belief that we have made it out to be. The cycle that drives industrial-technological civilization — science developing new technologies that are engineered into industries that provide improved instruments for the further development of science — is intrinsically infinitistic; as such, it is the negation of finitistic political theory. Progress, in contradistinction to perfection, is an infinitistic ideal; there is always the possibility of further progress.

Comte de Maistre’s Finitistic Political Theory was an expression of the finitistic, backward-looking assumptions of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization. In agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, transcendence is an exteriority, lying outside time; in industrial-technological civilization, transcendence is immanent, and nothing outside time exists. Perfection as a virtue and as an ideal no longer applies to expanding societies engaged in the continual process of self-transcendence. In infinitistic contexts, progress replaces perfection, although progress itself is as problematic an ideal as perfection.

Each macro-historical division of civilization — of which agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization is one — embodies distinctive assumptions, has risks and opportunities peculiar to its socio-economic structure, and struggles with distinction problems, none of which may be found in other macro-historical divisions. Agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, for example, was entirely free of large-scale industrial accidents, which are intrinsic to industrial-technological civilization, but was subject to permanent risk of famine, given the intensively local nature of the economy, in which economic units were isolated and people would starve if local crops failed.

Another example: in agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization one of the most central social and political issues is the control of the institutionalized church within the boundaries of political control. In industrial-technological civilization, this imperative of ecclesiastical control virtually disappears. The most successful economy of industrial-technological civilization, that of the United States, is predicated upon separation of church and state, to the point that there is complete laissez-faire in matters of religion, which we have discovered is conducive to the smooth and seamless functioning of a market economy. But, as we have seen above, agrarian-ecclesiastical civilizations tolerated only capitalism without markets, or highly restricted markets within traditional and legal parameters, so that for agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization the problem of how to contribute to the smooth and seamless growth of a market economy was a problem that literally did not even exist.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .