Why Freedom of Inquiry in Academia Matters to an Autodidact

11 November 2016

Friday

When I attempt to look back on my personal history in a spirit of dispassionate scientific inquiry, I find that I readily abandon entire regions of my past in my perhaps unseemly hurry to develop the next idea that I have, and which I am excited to see where it leads me. Moreover, contemplating one’s personal history can be a painful and discomfiting experience, so that, in addition to the headlong rush into the future, there is the desire to dissociate oneself from past mistakes, even when these past mistakes were provisional positions, known at the time to be provisional, but which were nevertheless necessary steps in order to begin (as well as to continue) the journey of self-discovery, which is at the same time a journey of discovering the world and of one’s place in the world.

In my limited attempts to grasp my personal history as an essential constituent of my present identity, among all the abandoned positions of my past I find that I understood two important truths about myself early in life (i.e., in my teenage years), even if I did not formulate them explicitly, but only acted intuitively upon things that I immediately understood in my heart-of-hearts. One of these things is that I have never been, am not now, and never will be either of the left or of the right. The other thing is, despite having been told many times that I should have pursued higher education, and despite the fact that most individuals who have the interests that I have are in academia, that I am not cut out for academia, whether temperamentally, psychologically, or socially — notwithstanding the fact that, of necessity, I have had to engage in alienated labor in order to support myself, whereas if I had pursued in a career in academia, I might have earned a living by dint of my intellectual efforts.

The autodidact is a man with few if any friends (I could tell you a few stories about this, but I will desist at present). The non-partisan, much less the anti-partisan, is a man with even fewer friends. Adults (unlike childhood friends) tend to segregate along sectional lines, as in agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization we once segregated ourselves even more rigorously along sectarian lines. If you do not declare yourself, you will find yourself outside every ideologically defined circle of friends. And I am not claiming to be in the middle; I am not claiming to strike a compromise between left and right; I am not claiming that I have transcended left and right; I am not claiming that I am a moderate. I claim only that I belong to no doctrinaire ideology.

It has been my experience that, even if you explicitly and carefully preface your remarks with a disavowal of any political party or established ideological position, if you give voice to a view that one side takes to be representative of the other side, they will immediately take your disavowal of ideology to be a mere ruse, and perhaps a tactic in order to gain a hearing for an unacknowledged ideology. The partisans will say, with a knowing smugness, that anyone who claims not to be partisan is really a partisan on the other side — and both sides, left and right alike, will say this. One then finds oneself in overlapping fields of fire. This experience has only served to strengthen my non-political view of the world; I have not reacted against my isolation by seeking to fall into the arms of one side or the other.

This non-political perspective — which I am well aware would be characterized as ideological by others — that eschews any party membership or doctrinaire ideology, now coincides with my sense of great retrospective relief that I did not attempt an academic career path. I have watched with horrified fascination as academia has eviscerated itself in recent years. I have thanked my lucky stars, but most of all I have thanked my younger self for having understood that academia was not for me and for not having taken this path. If I had taken this path, I would be myself subject to the politicization of the academy that in some schools means compulsory political education, increasingly rigid policing of language, and an institution more and more making itself over into the antithesis of the ideal pursuit of knowledge and truth.

But the university is a central institution of western civilization; it is the intellectual infrastructure of western civilization. I can affirm this even as an autodidact who has never matriculated in the university system. I have come to understand, especially in recent years, how it is the western way to grasp the world by way of an analytical frame of mind. The most alien, the most foreign, the most inscrutable otherness can be objectively and dispassionately approached by the methods of scientific inquiry that originated in western civilization. This character of western thought is far older than the scientific revolution, and almost certainly has its origins in the distinctive contribution of the ancient Greeks. As soon as medieval European civilization began to stabilize, the institution of the university emerged as a distinctive form of social organization that continues to this day. Since I value western civilization and its scientific tradition, I must also value the universities that have been the custodians of this tradition. It could even be said that the autodidact is parasitic upon the universities that he spurns: I read the books of academics; I benefit from the scientific research carried on at universities; my life and my thought would not have been possible except for the work that goes on in universities.

It is often said of the Abrahamic religions that they all pray to the same God. So too all who devote their lives to the pursuit of truth pay their respects to the same ancestors: academicians and their institutions look back to Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum, just as do I. We have the same intellectual ancestors, read the same books, and look to the same ideals, even if we approach those ideals differently. In the same way that I am a part of Christian civilization without being a Christian, in an expansive sense I am a part of the intellectual tradition of western civilization represented by its universities, even though I am not of the university system.

As an autodidact, I could easily abandon the western world, move to any place in the world where I was able to support myself, and immerse myself in another tradition, but western civilization means something to me, and that includes the universities of which I have never been a part, just as much as it includes the political institutions of which I have never been a part. I want to know that these sectors of society are functioning in a manner that is consistent with the ideals and aspirations of western civilization, even if I am not part of these institutions.

There are as many autodidacticisms as there are autodidacts; the undertaking is an essentially individual and indeed solitary one, even an individualistic one, hence also essentially an isolated undertaking. Up until recently, in the isolation of my middle age, I had questioned my avoidance of academia. Now I no longer question this decision of my younger self, but am, rather, grateful that this is something I understood early in my life. But that does not exempt me from an interest in the fate of academia.

All of this is preface to a conflict that is unfolding in Canada that may call the fate of the academy into question. Elements at the The University of Toronto have found themselves in conflict with a professor at the school, Jordan B. Peterson. Prior to this conflict I was not familiar with Peterson’s work, but I have been watching his lectures available on Youtube, and I have become an unabashed admirer of Professor Peterson. He has transcended the disciplinary silos of the contemporary university and brings together an integrated approach to the western intellectual tradition.

Both Professor Peterson and his most vociferous critics are products of the contemporary university. The best that the university system can produce now finds itself in open conflict with the worst that the university system can produce. Moreover, the institutional university — by which I mean those who control the institutions and who make its policy decisions — has chosen to side with the worst rather than with the best. Professor Peterson noted in a recent update of his situation that the University of Toronto could have chosen to defend his free speech rights, and could have taken this battle to the Canadian supreme court if necessary, but instead the university chose to back those who would silence him. Thus even if the University of Toronto relents in its attempts to reign in the freedom of expression of its staff, it has already revealed what side it is on.

There are others fighting the good fight from within the institutions that have, in effect, abandoned them and have turned against them. For example, Heterodox Academy seeks to raise awareness of the lack of the diversity of viewpoints in contemporary academia. Ranged against those defending the tradition of western scholarship are those who have set themselves up as revolutionaries engaged in the long march through the institutions, and every department that takes a particular pride in training activists rather than scholars, placing indoctrination before education and inquiry.

If freedom of inquiry is driven out of the universities, it will not survive in the rest of western society. When Justinian closed the philosophical schools of Athens in 529 AD (cf. Emperor Justinian’s Closure of the School of Athens) the western intellectual tradition was already on life support, and Justinian merely pulled the plug. It was almost a thousand years before the scientific spirit revived in western civilization. I would not want to see this happen again. And, make no mistake, it can happen again. Every effort to shout down, intimidate, and marginalize scholarship that is deemed to be dangerous, politically unacceptable, or offensive to some interest group, is a step in this direction.

To employ a contemporary idiom, I have no skin in the game when it comes to universities. It may be, then, that it is presumptuous for me to say anything. Mostly I have kept my silence, because it is not my fight. I am not of academia. I do not enjoy its benefits and opportunities, and I am not subject to its disruptions and disappointments. But I must be explicit in calling out the threat to freedom of inquiry. Mine is but a lone voice in the wilderness. I possess no wealth, fame, or influence that I can exercise on behalf of freedom of inquiry within academia. Nevertheless, I add my powerless voice to those who have already spoken out against the attempt to silence Professor Peterson.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Atlantic Charter, Atlanticism, and Western Civilization on the Eve of another Bilderberg Conference

9 June 2016

Thursday

Once again I find myself without an invitation and shut out of the Bilderberg conference. Today, Thursday 09 June 2016, the Bilderberg Group is beginning its 64th conference, this time held in Dresden, Germany. Dresden was once called “Florence on the Elbe” as it was once a cultural center and renowned for its beautiful architecture. Dresden remained intact throughout most of the Second World War, and many believed that there was a tacit quid pro quo according to which Dresden would be spared. The Dresdeners were disabused of this notion as the city was destroyed by one of the most devastating Allied air raids of the entire war, conducted a few days after the Yalta conference wrapped up (I previously wrote about the bombing of Dresden in Mass War and Mass Man, inter alia).

There is, then, something ironic about holding a Bilderberg conference in Dresden, though perhaps the intention was symbolic, to demonstrate that Dresden is once again a world-class city, reclaiming its place as a rebuilt “Florence on the Elbe,” with the reconstructed Frauenkirche and most of the rest of its historic center restored. The Atlanticism represented by the Bilderberg Group (cf. Bilderberg and Atlanticism) was predicated upon the defeat of Nazi Germany, and the defeat of Nazi Germany meant that the brutality of Nazism had to be countered by an even greater brutality. If there had been an internal uprising against the Nazis, the German people could have made the country ungovernable, but even after military defeat was certain the Germans continued to fight. The destruction of Dresden was collateral damage in this fight, and the reconstruction of Dresden has been, in a sense, a triumph of Atlanticism — the re-unification of Germany in the context of a peaceful and prosperous Europe.

Much of Dresden’s historic center has been rebuilt.

Recently in Counterfactuals in Planetary History I noted that the post-war social order collectively created by the victorious Allies of the Second World War has been unraveling since the end of the Cold War. This is no secret, and few would disagree. The disagreement emerges over the next form of the “new normal” that will follow the present period of drift. One unspoken assumption is that Western Civilization will continue on in more or less its present form, and will continue to be central to planetary civilization. In other words, the assumption is that the unraveling of the post-war social order is not the unraveling of Western Civilization. We may be concerned about the resurgence of Putin’s Russia and the rise of China as a technologically sophisticated world power, but we don’t seriously contemplate the end of Western Civilization itself, even if we see its relative decline.

The traditions of Russian civilization — what Samuel Huntington identified as Orthodox civilization — and Chinese civilization are in many cases openly hostile to many of the principles central to Western Civilization in their anti-individualism, non-transparency, and preference for despotism. A world in which the Chinese or the Russians held the central place in the international system that the US now holds would be a world in which almost all the ideas embodied in the Atlantic Charter were either ignored or actively subverted. This would not be a world safe for democracy. But two great wars were fought in order for the world to be made safe for democracy, and yet democracy finds itself embattled once again. How did this happen?

With the rise of the US to world power status, Western Civilization has been Atlantic civilization, represented by Europe on the one shore, and North America on the other. The civilization of Atlanticism constituted what the shared tradition of Western Civilization had become in the course of its seriation. The principles for which this civilization stood were embodied in the Atlantic Charter. The Atlantic Charter was, in turn, heavily influenced by Wilson’s 14 Points, which came before, and went on to influence the founding principles of the United Nations, hence the global social order. While Yalta was the conference on the post-war settlement that came near the end of the Second World War, the Atlantic Charter was the agreement on the post-war settlement that came near the beginning of the war, even before the US had officially entered the war, and thus constituted the explicitly stated principles in defense of which the US entered the war.

Atlanticism on both sides of the Atlantic is seriously threatened at present. Both of the presumptive presidential nominees of the two major political parties in the US are openly populist and protectionist, and both major parties are tearing themselves apart internally over the choice the nominee. No doubt matters will settle down in time, someone will be elected president, and things will go on as before. But even if this happens, and all the shouting was for naught, it is obvious that the political class in the US no longer believes in the principles it once fought to preserve. The élites of the western world have contributed to the unraveling of the social order implied by the principles enumerated in the Atlantic Charter and imperfectly embodied in practice by institutions such as the United Nations. Temporary political advantage seems a sufficient pretext to abandon even a pretense to the ideals of an open society.

In Europe, the great political project of the post-war era — the EU — faces increasing popular resistance as the initial promises of the EU to deliver economic growth have failed to bear fruit, while the non-democratic character of the institution has become increasingly obvious. In other posts I have noted that democracy does not come naturally to the Europeans, who even in an age of popular sovereignty have managed to erect the appearance of democracy without the substance of democracy (cf. Europe and its Radicals). The EU is one of the worst offenders in this respect. It is not merely non-democratic, but often openly anti-democratic. When any nation-state has voted against the agreements that implement the EU, these votes have been set aside or ignored, and the project has continued on. (Personally, I would like to see the vote for Britain to leave the EU to go against the EU, just to hand a resounding comeuppance to the pretensions of the EU — but this vote, too, would probably be ignored and it will be said that Britain “initially rejected” the EU, but then, after another vote, or two, or three, they wisely changed their minds.)

Europe and the EU is not the only offender against the ideals of democracy. The technocratic élites of western civilization so profoundly distrust the peoples they are supposed represent that they created a technological panopticon in which every detail of the lives of the public is laid open to the minutest observation, while the shadowy watchers reveal nothing of themselves, so that the ancient question — who watches the watchers? — must remain unanswered. This is the meaning of the universal surveillance state as revealed by Edward Snowden, who had to flee the US after making his revelations. This is not merely anti-democratic, but openly contemptuous of the spirit of democracy.

The point here is that singling out the non-transparency of the Bilderberg Group — one of the last remaining vestiges of authentic Atlanticism — is beside the point. The EU itself is non-transparent, and seems to be so by design. And the universal surveillance of the US is non-transparent, and has been made so by design. Focusing on the Bilderberg Group is to fail to see the forest for the trees.

The unraveling of the post-war political consensus, once held in place by the stable dyad of the Cold War, continues apace because the “leaders” of the nation-states putatively representing Western Civilization simply do not believe the platitudes and glittering generalities that they spout. Their contempt for the democracy they claim to espouse is a glaring hypocrisy lost on no one — least of all the Chinese and the Russians.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Seriation of Western Civilization

19 March 2015

Thursday

At least four times in the history of our planet, civilization has independently emerged, and we possess a fairly detailed archaeological record of a complete series in each of these four cases of the development from the most rudimentary settled agriculturalism up to a fully developed and articulated agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization. This is by no means an exhaustive account of terrestrial civilization. Civilization, like life itself, is a branching bush that, once started, repeatedly bifurcates and diverges in unprecedented ways from its root stock. There are other forms of civilization, and probably other instances of independent origin. I suspect, for example, that in the Western hemisphere that a complete and independent seriation of civilization occurred at least twice, and perhaps more than twice.

Today I will not consider the phenomenon of civilization taken whole, but I will rather consider the seriation of Western civilization in isolation. As a westerner myself (well, sort of a westerner, as my people are all Scandinavian, and Scandinavian civilization, i.e., Viking Civilization, was subsumed under an expanding Western Civilization), I am understandably most interested in Western Civilization, but Western Civilization should also be interesting to anyone who studies civilization as such, due to its many unique features. I have commented elsewhere that it is today considered in bad taste to compare civilizations; nevertheless, I must run the risk of doing so in order to freely and openly discuss the features that differentiate western civilization from other civilizations — and also those features that mirror other civilizations. What makes Western Civilization unique are those unprecedented historical mutations that did not occur in other civilizations — viz. the Age of Discovery, the scientific revolution, and the industrial revolution — and which we then compare with other civilizations as a baseline for reference.

To spell out a bit of my conceptual framework explicitly, a cluster (as I use the term) is a geographical region comprising several closely related civilizations that have been the result of idea diffusion from a common source (or originating more-or-less simultaneously). This is a synchronic conception. A cluster contains several series. A series is a sequence of civilizations in time, related through descent with modification, more or less laid end to end, and inhabiting more or less the same geographical region or geographical trajectory. Civilizations in a common series are related by inheritance. This is a diachronic conception. Civilizations in a cluster are synchronically related to each other; civilizations in a series are diachronically related to each other. Thus from the West Asian Cluster there emerges the series that becomes western civilization as it projects itself along a continual western trajectory out of Mesopotamia and the Levant.

A very comfortable-looking reconstruction of an interior at Çatal Hüyük, which gives the appearance of civilized life.

Civilizational series admit of what archaeologists call seriation. In so saying I am using the term more comprehensively that is usual. Seriation has been defined as:

A relative dating technique in which artifacts or features are organized into a sequence according to changes over time in their attributes or frequency of appearance. The technique shows how these items have changed over time and it is a way to establish chronology. Archaeological material, such as assemblages of pottery or the grave goods deposited with burials is arranged into chronological order. The types that make up the assemblages to be ordered in this way must be from the same archaeological tradition and from a single region or locality. Once the variations in a particular object have been classified by typology, it can often be shown that they fall into a developmental series, sometimes in a single line, sometimes in branching lines more as in a family tree. The order produced is theoretically chronological, but needs archaeological assessment. Outside evidence, such as dating of two or more stages in the development, may be needed to determine which is the first and which the last member of the series.

Kipfer, Barbara Ann, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology, New York: Springer, 2000, p. 505

It is atypical to apply seriation to an entire civilization, and in fact it could be said that I am misusing the term, as the definition above cites “artifacts or features,” and a civilization is neither an artifact or a feature in the usual senses of these terms, but includes both of them and more and better besides. The power of seriation is that once you have an understanding of a developmental sequence, you can “connect the dots” when a people have moved location, identifying when a particular developmental stage terminates at one location and then picks up again at another location. Such a developmental trajectory moving ever westward characterizes the origins and development of western civilization.

Ritual figurine from Çatal Hüyük; the area excavated to date includes a large number of structures believed to be shrines or temples, demonstrating a robust ideological infrastructure.

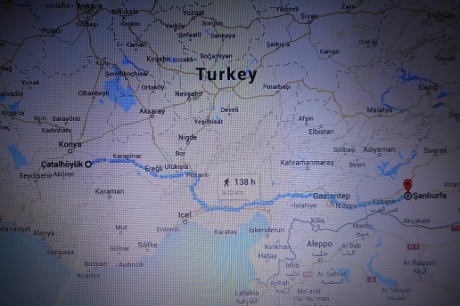

In my post on The Philosophical Basis of Islamic State I noted that I called the many civilizations having their origins in Mesopotamia and the Levant the West Asian Cluster. Western civilization has its earliest origins in the West Asian Cluster, and in the earliest years of the rudimentary civilization that emerged here we find a network of family resemblances that overlap and intersect (to borrow a Wittgensteinian phrase). The earliest known site in the West Asian Cluster that has clear evidence of large scale social cooperation, and therefore can be considered a distant ancestor to civilization — proto-civilization, if you will — is Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Anatolia. Thought to be a ritual center predating even settled agriculture (specifically, Prepottery Neolithic A, or PPNA), the site has impressive megalithic architecture. Let us take this as the point of origin for civilization in the West Asian Cluster — it is our best scientific knowledge as of the present for the origins of our civilization.

Several hundred miles west of Göbekli Tepe is Çatal Hüyük, a famous Neolithic site often identified as the first urban settlement on our planet. (According to Google Maps it takes 138 hours to walk the 670 km from one site to the other. If one could walk 8 hours per day, it would take 17 days to make the journey. If you walked fast, you might make a round trip in one moon.) Çatal Hüyük has been extensively studied, though not fully excavated, and while the life of the people would have been extremely rudimentary by the measures of what we call civilization today, it nevertheless possesses all the essential elements of civilization: an urban settlement supported by agricultural suburbs, with division of labor, art and religion, and trade with neighboring peoples.

The next famous site on this westward trajectory is that of Pločnik in present-day Serbia. The settlement (perhaps town) of Pločnik represents what is called the First Temperate Neolithic. In other words, the techniques of farming in Mesopotamia and the Levant that characterized the agricultural revolution as it was first realized in this cluster were adapted for use in a temperate climate, and this both demanded and inspired further technological innovations. Pločnik may be the first site at which extractive metallurgy was practiced with the production of copper and bronze implements and decorative items.

Vinča-Pločnik Culture, Late Mesolithic (5th mill. BC). (Photo Credits: Carlos Mesa) Double-Headed figure, Cayonu, Turkey.

If you look at the relationship of Çatal Hüyük and Pločnik on a map, you will see that the path takes you through Thrace and present-day Bulgaria. When I noticed this, I did some research to find out about Neolithic archaeology in Bulgaria, and, sure enough, there were remains of the right age located almost exactly between Çatal Hüyük and Pločnik, so that one can literally see in the archaeological remains of material culture the trajectory of peoples as they emerged from subtropical climate of Mesopotamia and passed through Anatolia on their way north and west.

As settled agriculture gained a foothold in the Balkan Peninsula, the region was a quiet backwater for thousands of years as spectacular civilizations still known for the monumental architecture rose and fell in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia. Little of note seemed to be happening as a result of the humble farming communities of the First Temperate Neolithic in the Balkans, until a new kind of civilization took shape in Greece. The Greeks, never shy to own their accomplishments, knew that they had created a new kind of civilization very different from the Persians on their border, whom they repeatedly and heroically resisted.

The Acropolis and the Parthenon represent a different approach to monumental architecture than that of Egypt, Anatolia, or Mesopotamia.

The cultural heritage of Greece, and especially the art, architecture, philosophy, and literature of Athens and Attica was projected back into West Asia by the conquests of Alexander the Great, but Alexander died young, and while the impress of Greek civilization can still be detected in West Asia where Alexander’s troops marched all the way to India, the tradition of Greek civilization was taken in another direction once again farther West, when Roman power emerged as the dominant political regime in the Mediterranean Basin. When Alexander’s unsustainable empire was divided after his death, Greece proper, with all its rich cultural traditions, was conquered by the Romans, who had a great enthusiasm for Greek civilization. It became a fashion among wealthy collectors to seek out the finest examples of Corinthian pottery, in a way that is precisely parallel to the tastes of antiquarians in our own time.

Roman farmers didn’t get much glory, but they made the empire possible. Moreover, they made what followed the empire possible also.

The Roman Empire represents the greatest spatial expansion and the longest temporal duration of the civilizations directly derived from the West Asian Cluster, with the possible exception of Islamic civilization, but in each of these cases there is a question as to what constitutes “direct” derivation from the West Asian source. Only with the collapse of Roman power in the west and the admixture of elements from the West Asia Cluster with indigenous European cultures do we see the emergence of a distinctly western civilization. Rather than ex oriente lux, a light from the east illuminating western barbarism, we have in occidente lux, the ancient light of eastern civilization given new life as it enters into Europe. And by this time in history, the original five clusters of civilization had repeatedly bifurcated and had begotten a range of mixed civilizations that were to confront western civilization as it began its relentless global expansion.

When Roman power collapsed in the west, the empire divided and civilization bifurcated. In the east, the empire became more Greek in character, and Byzantine civilization emerged. In the west, those traditions transmitted from Mesopotamia, Anatolia, Greece, and the Roman Mediterranean once again migrated further west and in so doing found themselves in the midst of the inhospitable barbarism of Western Europe. For all Europe’s early productivity of what archaeologists call “cultures” (and which I would call proto-civilizations, if not civilization simpliciter), Europe did not make the breakthrough to civilization proper, but had to wait for the examples of the West Asian Cluster to show it the way to civilization by way of idea diffusion (which I would now, following Cadell Last, prefer to call idea flow).

In the farthest western peninsula of Eurasia Western Civilization finally took on its definitive and distinctive form as a new civilization arose and became what we now call medieval Europe. But this was not the end. At the farthest western edge of this western peninsula of Eurasia, on an island jutting into the Atlantic, the industrial revolution began in the final quarter of the eighteen century, and this was to inaugurate an entirely new kind of civilization — industrial-technological civilization — that is even today consolidating its planetary expansion. This industrialized civilization leapt over the Atlantic Ocean and found in North America especially fertile soil in which to grow, and so Western Civilization continued in its westward migration. Now that industrial-technological civilization has expanded on a planetary scale, civilization has nowhere to go but upward and outward. When this happens, another novel form of civilization will take shape.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

American Religious Individualism

22 August 2012

Wednesday

The idea of the individual has been central to Western Civilization; we can discern its earliest manifestations in ancient Greece, when potters signed their work and bragged that they were better than other potters; we can see its further development in the Italy of the renaissance, when men of virtú like Machiavelli and Lorenzo the Magnificent forcefully asserted themselves as rightful masters of their time; we can see the new forms that it has taken after the Industrial Revolution, where the office towers of New York, like the medieval towers of San Gimignano, assert the ascendancy and priority of the individual.

Whether you love it or hate it, you have to acknowledge that the US is where individualism has reached its most unconditional realization. Some people glory in American individualism, and some despise it. If a member of the commentariat or the punditocracy wants to put a positive spin on individualism, they will call it “rugged individualism,” whereas if they want to put a negative spin on individualism, they will call it “rampant individualism.” There are plenty of examples of both of these attitudes, and I invite the reader to stay alert for these linguistic clues in future reading.

Jean-Paul Sartre said of the skyscrapers of New York City, “Seen flat on the ground from the point of view of length and width, New York is the most conformist city in the world… But if you look up, everything changes. Seen in its height, New York is the triumph of individualism… There are individuals in America, just as there are skyscrapers. There are Ford and Rockefeller, Hemingway and Roosevelt. They are models and examples.”

When earlier today I posted a longish piece on Tumblr about Appearance and Reality in Demographics, I continued to think about the recent poll results that I mentioned there, WIN-Gallup International ‘Religiosity and Atheism Index’ reveals atheists are a small minority in the early years of 21st century, as well as an earlier poll from the Pew Forum, U. S. Religious Landscape Survey, that I mentioned some years ago (in 2008) in More on Republican Disarray. In particular, I thought about how wrong prognosticators, forecasters, and social commentators have been about the development of religion in the US. There is an obvious reason for this. The US is not only a disproportionately religious nation-state (as revealed in numerous polls), it is also, as I noted above, a disproportionately individualistic nation-state, and the confluence of these ideological trends, the religious and the individualistic, means that US culture is marked by religious individualism and individual religion.

I touched on this peculiar character of religion in America — i.e., religious individualism — in my post American Civilization, in which I cited the song Highwayman, jointed performed by Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, and Waylon Jennings (and written by Jimmy Webb). This is an obvious pop culture example of what I am getting at, but the careful reader of classic American fiction will also reveal a religious individualism that frequently issues in pluralism, diversity, and the frankly eclectic. To put it bluntly, people believe whatever they want to believe.

Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash, and Kris Kristofferson, left to right, recorded the Jimmy Webb song The Highwayman and made a commercial success of it.

The attempt to pigeonhole American religious belief and practice always founders on the rock of religious individualism, which cannot be reliably classified in ideological terms. It is not consistently left or right, radical or traditional, liberal or conservative, activist or quietist — or, rather, it is all of these things at different times for different individuals.

Norman Rockwell’s iconic image of freedom of worship is for many a paradigmatic representation of American religiosity, which synthesizes in the single image the conformity and individualism that Sartre saw in American skyscrapers. Each worships according to his own conscience, but it just happens (I guess as a matter of pure chance) that everyone shows up at the white steepled church in the center of a picturesque American small town.

Individual religion takes the form of individual choice, and different individuals choose differently for themselves, and choose differently at different times in their life. This was one of the interesting results of the Pew Forum poll I mentioned above, which found a high level of religious observance in the US (everyone expected that), but when prying deeper found that, “More than one-quarter of American adults (28%) have left the faith in which they were raised in favor of another religion.”

This Rockwell image of American religiosity, no less iconic but perhaps a tad more realistic than the image above, shows an inter-generational solidarity of faith that defies the cool disinterest of the hip crowd. This is, again, like the other Rockwell image above, what many people want to believe about American religious life.

While this may not sound too shocking prima facie, it would be difficult to overemphasize how historically unusual this is. One of the conflicts that marked the shift from the medieval world to the modern world in European history was that between the personal principle in law and the territorial principle in law (which latter emerges with the advent of the nation-state). Given the personal principle in law, an individual is judged according to his community. If you were a Christian on pilgrimage to the Holy Land and were accused of a crime in a Muslim country, you would be dealt with according to Christian law, not Muslim law. That how it was supposed to work, and sometimes it did work that way, and for the decentralized societies of medieval Europe the personal principle in law fit the loosely coupled structures of a nearly non-existent state.

A much less flattering portrayal of American religiosity is to be found in Sinclair Lewis’ novel Elmer Gantry. To reconcile the diverse imagines of Rockwell and Lewis you can imagine Elmer gantry preaching to the assembled small town congregation whose sincere faces, bowed in prayer, are depicted by Rockwell.

The personal principle in law persists today in the institution of diplomatic immunity, but apart from diplomats, those accused of a crime will be tried according to the law of the geographically defined nation-state where the crime occurred, and this legal process will have little or nothing to do with the ethnicity or traditional community of the accused individual. Again, that’s the way it’s supposed to work, though it is not difficult to cite violations of this principle.

College campuses and prisons are common sites for religious proselytizing, since young people going to college and away from home for the first time, and incarcerated persons having passed through the justice system, are particularly apt to convert to a faith not directly involved in their earlier life experience.

The personal principle in law is all about ethnicity and tradition and individual identity being defined by a traditional community, which in turn defined the individual in terms of his or her role in that community. The idea that an individual might change their religion was like suggesting that an individual could put on or take off an identity like a suit of clothes. This would have been utterly incomprehensible to our ancestors; for the US it is now a fait accompli, and the basis for the organization of our society. Just as serial monogamy has come to characterize American courtship and marriage patterns, so too serial faith choices, adopted sequentially throughout the life of the individual as that individual experiences personal crises that precipitate temporary religious identification, characterize American religious patterns.

Benjamin Franklin, the quintessential American, moved from Boston to Philadelphia and thus inaugurated the quintessentially American tradition of self-reinvention through geographical mobility.

Indeed, one of the perennial themes of American life is that of personal re-invention (i.e., the putting on and taking off of identity). In the US, failure is not final. If things aren’t working out for you in Boston, you can move to Philadelphia, as Benjamin Franklin did. In a social context of personal re-invention and geographical fungibility, what counts is not one’s abject subordination to the community into which one happens to be born, but one’s cleverness and persistence in finding a place where one can feel at home. Part of this personal quest is also finding a faith in which one can feel at home, and this is not necessarily the faith of one’s parents or of one’s community.

In the context of religious individualism, orthodoxy counts for nothing. Or it counts for everything, but only because each man has his own orthodoxy, and there is no social mechanism in place in industrial-technological civilization to force the acquiescence of any individual to any other individual’s orthodoxy.

Even those who celebrate orthodoxy and who would welcome mechanisms of social control to force acquiescence to orthodoxy, cannot escape, at least while in America, the necessity of defining their own orthodoxy on their own terms. They are, in Rousseau’s terms, forced to be free, which in this context means they are forced to be religious individualists.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Biohistory and Biopolitics

25 February 2012

Saturday

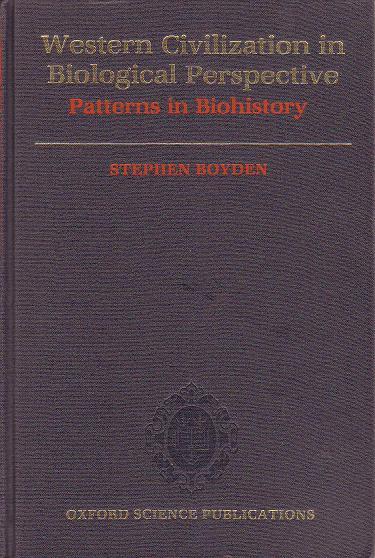

About a week ago I was browsing in a used book store and had the good fortune to come across a book that I’d never heard of, but just the title told me that it was something that would immediately appeal to my particular perspective on history. The book, which I purchased, is Western Civilization in Biological Perspective: Patterns in Biohistory by Stephen Boyden.

The author, I learned upon investigation, has had a long and varied career — exactly the sort of thing that would give a person the kind of broad perspective that would be needed to write the history from western civilization from a biological perspective.

Recently, in a series of posts — Geopolitics and Biopolitics, Addendum on Geopolitics and Biopolitics, and A Further Note on Geopolitics and Biopolitics — I took the idea of “biopolitics” and “biopower” from Foucault and developed it as a possible alternative to geopolitics as a form of strategic analysis.

There is nothing of Foucault in Boyden’s book. Foucault’s name does not appear in the index, and a search of the text reveals no reference to Foucault. More importantly, the nature of the text itself is utterly divorced from Foucault and from continental philosophy generally speaking — it seems to employ no terminology or concepts in common with the continental tradition, and treats of none of the familiar preoccupations of this tradition (Marx and Freud are mentioned in passing in a couple of places, but are in no sense a focus of the text; they do not even influence the terms of the discussion).

Although Boyden’s treatment of biohistory has virtually nothing to do with Foucault, I can’t imagine a more perfect theoretical foundation for biopolitics than a scholarly treatment of biohistory as found in Boyden. Boyden brings the kind of Anglo-American objectivity (though he is an Aussie) to biohistory that could greatly sharpen and improve the formulations of biopolitics, which latter are vulnerable to the enthusiasms of continental philosophy. Foucault himself insisted upon the “grayness” of genealogy, and the patient analysis of Boyden constitutes a de facto genealogy of biopower, which is something Foucault said that he had to write, but which he did not get to before he died.

A biohistory of civilization would be, in effect, an ecology of civilization, and Boyden employs ecological concepts throughout his study. One way to bring further analytical clarity to an ecology of civilization would be the systematic use of ecological temporality in the exposition of biohistory. This is something that I will think about.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .