Happiness: A Tale of Two Surveys

4 October 2020

Sunday

The happy people of Togo.

The World Happiness Report has been published for every year since 2012 (with the exception of there being no WHR for 2014) by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network. A number of influential persons are involved in the report (e.g., the economist Jeffrey Sacks), there is big money behind the effort (e.g., sponsorship from several foundations and companies), and there are several major universities associated with the effort (Columbia, UBC, LSE, Oxford). Of course, the UN is involved also, via the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, and the report itself incorporates extensive discussions of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Each year when the WHR is published there are predictably celebratory reports in the legacy media, along with the equally predictable hand-wringing and pearl-clutching in regard to the countries that occupy the bottom of the list.

Happy children in Togo.

With so much talent and money and reputation involved, the report not surprisingly has a sophisticated methodology. Indeed, the methodology is so sophisticated that it might be called “opaque”; I had to spend quite a bit of time reading the fine print to figure out how it was that they were coming up with their happiness rankings. Of course, the reports in the media feature the rankings, and only the merest cursory description of the methodology. In this, the WHR is incredibly effective in promoting a narrative of national success and failure without many people looking into the guts of their happiness machinery.

More happy people in Togo.

The WHR each year starts out with an explanation of the Cantril Ladder, which seems prima facie to be a relatively straight-up measure of subject well-being. The Cantril Ladder asks survey participants, “…to value their lives today on a 0 to 10 scale, with the worst possible life as a 0 and the best possible life as a 10.” (2015 WHR, p. 20) The Cantril Ladder, however, is only the beginning of the fun. The number they derive from the Cantril Ladder question is then run through six different equations, each of which brings another factor into the “happiness” calculation. The six additional factors are “GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make life choices, generosity, and freedom from corruption.” (p. 21)

More happy children in Togo.

Of these six factors, two — per capita GDP and healthy life expectancy — are “hard” numbers for economists (in other words, they are relatively hard numbers, but these numbers can be gamed as well). Two factors require additional questions that probe subjective well-being, and these are social support and freedom to make life choices. To assess social support respondents were asked, “If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them, or not?”; to assess freedom to make life choices, respondents were asked, “Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your freedom to choose what you do with your life?” The remaining two factors are a bit squishy — generosity and freedom from corruption — by which I mean that there are measurements that could be taken for these, but subjective perceptions can also be involved. To measure generosity respondents were asked, “Have you donated money to a charity in the past month?” This strikes me as a good metric. To measure corruption respondents were asked, “Is corruption widespread throughout the government or not?” and “Is corruption widespread within businesses or not?” This strikes me as much less satisfactory, especially since bodies like Transparency International have made an effort to compile corruption indices, but it is a good measure in so far as it is more self-reported well-being data.

Yet more happy people in Togo.

Once the numbers are crunched according to their formulae, the 2015 WHR ranks the following as the ten happiest countries in the world:

1. Switzerland (7.587)

2. Iceland (7.561)

3. Denmark (7.527)

4. Norway (7.522)

5. Canada (7.427)

6. Finland (7.406)

7. Netherlands (7.378)

8. Sweden (7.364)

9. New Zealand (7.286)

10. Australia (7.284)

One cannot but notice that these are all western, industrialized nation-states, mostly European, and indeed mostly northern European.

More happiness in Togo.

In the same 2015 WHR, Togo comes in dead last. Do I believe that the people of Togo are the least happy on Earth? No, I don’t. However, I do believe that well-meaning philanthropic foundations believe that Togo needs to change, and that it especially needs the “help” of these philanthropic foundations to better acquaint them with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, so that they, too, can be made as happy as the northern European countries that top the WHR. I’m certainly not saying that everything in Togo is fine and dandy. There was serious political unrest in the country in 2017-2018 (cf. 2017–2018 Togolese protests), but, given what we delicately call the “social unrest” in the US during the summer of 2020 (also known as riots, vandalism, looting, arson, assault, and murder), I’m not sure that things are worse in Togo than the US, even if Togo is objectively impoverished compared to the US.

“Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy.”

Now, being myself from northern European stock (Norwegian on my father’s side and Swedish on my mother’s side), I could point with pride to the narrative of national success for Scandinavia that is a common feature of international comparisons of this kind, except that, being culturally Scandinavian, and having traveled in these countries, I know what the people are like. I feel very familiar in this context, and, frankly, I enjoy being in Scandinavia and being among other Scandinavians, with whom I share much in terms of temperament and attitude to life. I have also traveled in southern Europe and experienced the very different pace and temper of life, as well as the different pace and temper of life in South America, where I have traveled extensively. I have not (yet) had the good fortune to travel in Africa, much less to Togo itself, so I cannot speak from personal experience in regard to these peoples, but I do not doubt that they possess a full measure of well-being and life satisfaction such as only could be expressed in terms of their culture, much as well-being and life satisfaction in Scandinavia is expressed in terms of Scandinavian culture. What passes for “happiness” among wealthy, industrialized, Nordic peoples of a stoic disposition is not necessarily what would pass for “happiness” among west Africans.

Good times in Togo.

I have focused on the 2015 WHR report (which is not the most recent) because it provides an interesting contrast to another report from 2015, which is the WIN/Gallup International annual global End of Year survey. WIN/Gallup International collaborated on these annual surveys for ten years, from 2007 to 2017. Both WIN and Gallup International are still in business, but they no longer collaborate on these annual surveys; Gallup International (GIA) is not be confused with Gallup Inc., which two are distinct polling companies. The annual End of Year (EoY) surveys can be on a variety of questions (for 2018 the EoY survey was on political leadership), but happiness has been the focus of polling on several occasions. With these EoY surveys, Gallup International takes a sample of about 1,000 persons each from about 60 countries, always including the G20 plus a sampling of other nation-states that together represent better than half of the global population.

Togolese bananas

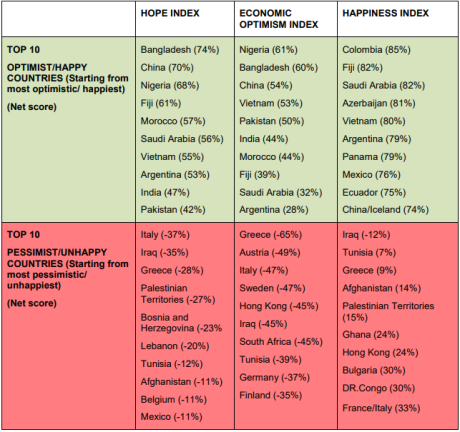

The methodology of the WIN/Gallup International EoY 2015 survey on happiness was a lot simpler than than Byzantine methodology of the 2015 WHR. WIN/GIA asked three questions:

● Hope Index: As far as you are concerned, do you think that 2016 will be better, worse or the same than 2015?

● Economic Optimism Index: Compared to this year, in your opinion, will next year be a year of economic prosperity, economic difficulty or remain the same for your country?

● Happiness Index: In general, do you personally feel very happy, happy, neither happy nor unhappy, unhappy or very unhappy about your life?

It is an interesting feature of these questions that the first two are framed in terms of predictions — a better next year and a more prosperous next year — but at bottom all three of these questions are questions that probe the individual’s sense of subjective well-being, albeit well-being sometimes projected into the future. Moreoever, WIN/GIA’s numbers aren’t run through a number of equations that filter these measures of subjective well-being through a variety of other factors.

Home, sweet home, in Togo.

When WIN/GIA crunched their numbers, the top ten rankings of the happiest places on the planet were radically different from those of the WHR, including a significant number of wealthy, industrialized European nation-states ranked in the bottom ten of the hope, optimism, and happiness indices:

1. Colombia (85%)

2. Fiji (82%)

3. Saudi Arabia (82%)

4. Azerbaijan (81%)

5. Vietnam (80%)

6. Argentina (79%)

7. Panama (79%)

8. Mexico (76%)

9. Ecuador (75%)

10. China/Iceland (74%)

We’ve already seen the very different methodologies employed by these two systems of ranking happiness around the world, so we understand how and why they differ, but what exactly does this difference mean? Bluntly, and in brief, it means that if you simply ask people if they are happy, you get results like WIN/GIA; if you run self-reported happiness through a filter of economics, you get results like WHR. Another way to frame this would be to say that the WHR implicitly incorporates Maslovian assumptions built into its rankings, such that a number of physiological and social needs must be met before we can even consider the question of happiness; if we interpret happiness as a form of self-actualization, we can see the relevance of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to sophisticated rankings of happiness that incorporate many other factors.

How much weight should we give to self-reported well-being? Should we be factoring in metrics other than subjectively reported happiness in attempting to measure happiness? Are individuals not their own best judge of their own happiness? There is a certain irony involved in economists assuming that individuals are not their own best judge of their own happiness, as it is economists who are always telling us that individuals are always the best judge of how their own earnings should be spent, because an individual exercises a close and careful oversight over money he himself has earned, while governments collecting money through taxes are spending money they did not themselves earn, and so are likely to exercise less stringent oversight.

More to the point, should elaborate polling methodologies with a pretense to represent self-reported well-being, but which in fact represent economic measures, drive analysis and policy? If we are to take happiness rankings as the basis of policy prescriptions, as the WHR position their study, but using the WIN/GIA numbers instead, then clearly the nation-states of the world should be emulating Colombia, Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, and Argentina. One might then conclude that the way to national happiness is surviving a 50 year civil war, capital punishment by beheadings in the street, having a one-party communist dictatorship, or having the largest sovereign debt default in history. The economists studying happiness would probably see such policy prescriptions as moral hazards. One suspects that the authors of the first WHR in 2012 saw the raw Cantril Ladder data, knew that it wasn’t going to give them the results that they wanted, and realized that they had their work cut out for them. For someone who knows how to crunch numbers, and who could get the raw data from which the WHR is compiled, it would be an interesting exercise to see exactly how much subjective well-being made any difference at all in the rankings.

If we take only per capita GDP in 2015 this is the top ten ranking:

1. Luxenbourg

2. Switzerland

3. Macao SAR

4. Norway

5. Ireland

6. Qatar

7. Iceland

8. US

9. Singapore

10. Denmark

We can immediately see that this list shares four entries with the WHR list — Switzerland, Iceland, Norway, and Denmark — while it shares only one entry with the WIN/GIA rankings — Iceland ties with China for tenth place in the WIN/GIA happiness index. From this we can see that GDP alone is 40% the same as the WHR rankings. To me this makes the WHR look more like factoring in some sense of subject well-being into economic rankings than it looks like factoring some economic data into self-reported happiness. Why not then simply use per capita GDP as a rough approximation for “happiness”? My speculation: economists already have to deal with ideas like homo economicus and the invisible hand, which are routinely chastised as being a vulgarly reductionist approach to the human condition; if happiness is to be characterized in economic terms, it needs to be done with style, verve, and not a little obfuscation if it is going to be carried off successfully in such a climate.

If one is going to indulge in the pleasant fantasy that public policy can be driven by concerns of individual well-being, one needs to be hard-headed about it if one’s policy proposals are to stand half a chance. The kind of people who formulate UN Sustainable Development Goals are content with the rankings of the WHR as a guide to policy, because it affirms their narrative, but the WIN/GIA rankings are effectively “opposite world” for the same people, and certainly not a guide to policy. If the happiest people in the world are to be found in Saudi Arabia and Azerbaijan, and with the people of Bangladesh and Nigeria topping the Hope Index, then UN measures of what constitutes the good life and hope for the future are more than a little off. And the WHR insists on UN Sustainable Development Goals almost to the point of salesmanship.

While I haven’t here fully showed you how the magic trick is done (I lack the expertise for that), I hope that I’ve showed you enough that the next time you see WHR rankings reported in the media, you will be skeptical of the relationship of these rankings to actual human happiness, which is certainly affected by economics, but is not identical with economics, and, moreover, there can be important outliers such that nearly optimal human happiness may occur with little or no relationship to economic measures that we might be tempted to substitute for happiness. Certainly, again, “well-being” is more than happiness, and economics makes a generous contribution to well-being, but when we use “well-being” as a rough synonym for happiness, and then rightly define well-being (in its other sense, not specifically related to happiness) by economic measures, this is the essence of the magic trick, and such a sleight of hand is not to be believed. I should sooner believe that all the people in Togo are miserable than believe that the contribution of happiness to well-being can be artfully dissimulated.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .