Islam Karimov and the Fate of Uzbekistan

3 September 2016

Saturday

Islam Karimov, ruler of Uzbekistan for decades, has passed away (the date of his death is officially yesterday, 02 September 2016, but he may have passed away a day or two earlier). The fate of Central Asia hangs in the balance of the uncertainty created by his death. Karimov seamlessly made the transition from President of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic to post-Soviet authoritarian, as Uzbekistan seamlessly made the transition from Soviet client to post-Soviet independent nation-state. As the Soviet model was the template for Karimov’s iron-fisted rule while alive, so too the Soviet model was the template for Karimov’s death: rumored to be in “ill-health” for several days, the state apparatus seemed to be gradually preparing the populace for the announcement of Karimov’s death. When the confirmation of Karimov’s death came, it came indirectly from a statement of condolences from the Turkey’s Prime Minister.

Central Asia during the Soviet period experienced decades of peace, at the cost of heavy-handed political repression. Those post-Soviet republics of Central Asia that managed to sustain the Soviet model after the end of the Soviet Union continued to enjoy peace, at the continued cost of political repression. Karimov followed the model of Soviet repression quite closely and was rewarded with a quiescent nation-state rarely mentioned in the news. It is easy to imagine, given the experiences of Afghanistan (never a Soviet republic) and Chechnya (never an independent nation-state), not to mention the wider disturbances of the region and the rise of terrorism as a major force in political affairs in the region, that some might be willing to openly endorse this kind of Soviet-style autocratic rule over the attempt to create open political institutions, which latter have never been successful in the region. The choice seems to one between state-sponsored repression or non-state repression.

The attempt, such as it was, to agitate for political openness and western-style democracy in Central Asia came in the form of the so-called “color revolutions” — primarily the “Rose” revolution in Georgia (November 2003), the “orange” revolution in Ukraine (November 2004), and the “Tulip” revolution in Kyrgyzstan (February 2005), though many other events are often counted as falling under this umbrella term. It is difficult to over-state the impact of the Central Asian “color revolutions” on the political elites of the region as well as in Russia, where they were perceived as an existential threat to the established political order. Visceral fear of another color revolution runs through the political class of Central Asia, and we even find the idea of a color revolution as a theme in hybrid warfare, as it is mentioned in the introduction to Russian General Valery Gerasimov’s article on hybrid warfare:

“The experience of military conflicts — including those connected with the so-called colored revolutions in north Africa and the Middle East — confirm that a perfectly thriving state can, in a matter of months and even days, be transformed into an arena of fierce armed conflict, become a victim of foreign intervention, and sink into a web of chaos, humanitarian catastrophe, and civil war.”

For authoritarians, the color revolutions were a metaphysical challenge to their rule, giving the appearance of an indigenous demand for political openness, but masking the reality of foreign-sponsored political division and chaos within the country. This may sound like the purest Soviet-style political paranoia, but, in this case, the false positives of Soviet-style political paranoia has been strongly selective: those old-guard leaders most effective in the repression of civil society have managed to retain their grip on power for the longest period of time. For an authoritarian to loosen his grip was to invite a flowering of civil society which might result in a color revolution, and, again from the authoritarian’s perspective, this would be a disaster (much as old-guard Chinese communists like Li Peng feared that the Tiananmen protest might be the seed of another Cultural Revolution, once again throwing China into chaos; cf. Twenty-one years since Tiananmen).

For western politicians, Soviet-style repression in Central Asia, while generally only gently criticized (if ever), was a metaphysical challenge to liberal democracy, giving the appearance of peace and prosperity on the surface, while masking the ugly reality of political repression, imprisonment, torture, and corruption. It is no wonder that the two sides cannot communicate with each other: they have different and incommensurable political ontologies.

There is, however, one point of agreement between authoritarians of Central Asia and their supporters on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the supporters of democracy and color revolutions: no one wants to see Uzbekistan, much less the whole of Central Asia, descend into chaos and anarchy. There is an overwhelming bias on behalf of stability, and this bias for stability will play a major role in the events that will unfold in the wake of the death of Islam Karimov.

The worry now, with Karimov out of the picture, is that a color revolution will occur, or Islamic forces will come to power, or both, and the state will tear itself apart in factional conflict between Karimov-style authoritarians, Islamists, and color revolutionists. In the event of chaos, each side will blame the other, but in the final result it doesn’t matter who starts it. And the worry beyond this worry is that, once one of the central nation-states of Central Asia descends into lawlessness, it will drag down the whole region in a domino effect of anarchy. No one wants to see a domino effect come to Central Asia, with the instability of any one nation-state spilling over into its neighbor, until the entire region becomes unstable and the factions become radicalized. None of this is inevitable. Turkmenistan managed to survive the death of a more bizarre autocratic ruler, Saparmurat Niyazov, who called himself “Türkmenbaşy,” and remains quiescent today. But it is unlikely that the Central Asia will remain quiescent forever.

. . . . .

. . . . .

Note Added 13 October 2016: The BBC has an interesting article about the succession in Uzbekistan, After Karimov: How does the transition of power look in Uzbekistan? by Abdujalil Abdurasulov

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Sunday

Air Force Space Command General John E. Hyten has announced the release of a new “Commander’s Strategic Intent” document (Commander’s Strategic Intent), which is a 17-page PDF file. Once you take away the front and back covers, and subtract for the photographs inside, there are only a few pages of content. Much of this content, moreover, is the worst kind of contemporary management-speak (the sort of writing that Lucy Kellaway of the Financial Times takes a particular delight in skewering). In terms of strategic content, the document is rather thin, but with a few interesting hints here and there. In a strange way, reading this strategic document from the Air Force Space Command is not unlike the Taliban annual statements formerly issued under Mullah Omar’s name (cf. 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015). One must read between the lines and past the rhetoric in an attempt to discern the reality beneath and behind the appearances. But strategic thought has always been like this.

After a one page Forward by General Hyten, there follows a page each on a summary of the contemporary strategic situation, priorities, mission, vision, Commander’s Intent, Strategy — Four Lines of Effort, and two and a half pages on “Reconnect as Airmen and Embrace Airmindedness,” then several pages with bureaucratic titles but interesting strategic content, “Preserve the Space and Cyberspace Environments for Future Generations,” “Deliver Integrated Multi-Domain Combat Effects in, from and through Space and Cyberspace,” and “Fight through Contested, Degraded and Operationally-Limited Environments,” eith a final page on “You Make a Difference, Today and Tomorrow.”

Strategic Situation

This section rapidly reviews the improving capabilities of adversaries, who are responding to technological and tactical innovations continually introduced by US armed forces in the field. While the document never explicitly mentions hybrid warfare, this is the threat that is clearly on the minds of those formulating this document. While noting the continued dominance of US forces in the global arena, the document mentions that this is, “an era marked by the rapid proliferation of game-changing technologies and growing opportunities to use them,” which is a central problem that will be further discussed below, and for which the document offers no strategic or systematic response (other than the commander’s overall strategic intent).

This survey of the strategic situation also mentions, “new international norms,” which I assume is an internal reference to the central strategic idea of this document discussed below in terms of norms of behavior intended to discourage adventurism that could compromise the global flow of commerce and information. If any new idea about norms of behavior are intended to be a part of the commander’s strategic intent, they are not formulated in this document. I would have left out these references to norms of behavior unless the idea were further developed in an independent section of the document.

Priorities

The priorities listed are three:

Win today’s fight

Prepare for tomorrow’s fight

Take care of our Airmen and our Families

A paragraph is devoted to each priority. The first two are sufficiently obvious. The last introduces a theme that is dominant in this document: the social context of the soldier. One way to look at this is that, in a political context in which it is not possible to raise the wages of soldiers to equal those of the professional class, one benefit that the institutional military can confer on the solider in lieu of higher pay is institutional support for the soldier and his family. An equally plausible interpretation, and perhaps an equally valid explanation, is that, given the technological focus of the Air Force, and especially Space Command, it would be easy to prioritize machinery over soldiers, or to give the impression that machinery has been prioritized over soldiers. Sending the explicit message that, “Airmen — not machines — deliver effects,” is to unambiguously prioritize the soldier over the machinery. (All of this is delivered in the nauseating language of social science and management-speak, but the meaning is clear enough regardless.) And with suicides among returning veterans as high as they are, the military knows that it must do better or it risks losing the trust of its warfighters.

Mission

The mission statement is predictable and uninspiring:

Provide Resilient and Affordable Space and Cyberspace Capabilities for the Joint Force and the Nation.

There is, however, one interesting thing on this page, which is the idea that “Resilience Capacity” is to be used as a metric for combat power. I have written about similar matters in Combat Power and Battle Ecology and Metaphysical Ecology Reformulated, especially as these concerns relate to the social context of the soldier (in the present case, the airman). One hint is given for how this is to be quantified: “Any capability that cannot survive when facing the threats of today and the future is worthless in conflict.” Certainly this is true, but how rigorously this principle can be applied in practice is another question. If everything that failed when exposed to actual combat conditions were to be ruthlessly rooted out, the military would be radically different institution than it is today. Is the Space Command ready for radical application of resilience capacity? I doubt it; it cannot alone defy the weight of institutional inertia possessed by all bureaucracies.

Vision

The vision statement is as lackluster as the mission statement:

One Team—Innovative Airmen Fighting and Delivering Integrated Multi-Domain Combat Effects across the Globe.

This is the kind of management-speak rhetoric that brings documents like this into ill repute, and deservedly so. Moreover, this page makes the claim that, “The three strategic effects of Airpower — Global Vigilance, Global Reach, and Global Power — have not changed.” This is exactly backward. Global vigilance, global reach, and global power are not effects of airpower, but causes of airpower. Such an elementary conceptual failure is inexcusable, but in this context I think it stems more from a desire to employ management-speak in a military context than from pure conceptual confusion. Despite these problems, this page introduces the phrase “aerospace nation,” which is a way to collectively refer to the soldiers and support staff who make aerospace operations possible (presumably also private contractors), and again drives home the message of the social context of the soldier and the institutional support for this social context.

Commander’s Intent

It is a little surprising to read here about the need to, “reconnect with our profession of arms,” which is as much as to admit that there has been a failure to maintain a robust connection with the profession of arms. This is a theme that connects with the support for the social context of the soldier. Part of this social context is home and family, part of this is support staff, and part of it is those directly involved in the profession of arms (i.e., the human ecology of the soldier). Reconnecting with the profession of arms is one method of strengthening the social context of the soldier and therefore the whole of the “aerospace nation.”

Strategy — Four Lines of Effort

So here are the four lines of effort:

• Reconnect as Airmen and Embrace Airmindedness

• Preserve the Space and Cyberspace Environments for Future Generations

• Deliver Integrated Multi-Domain Combat Effects in, from, and through Space and Cyberspace

• Fight through Contested, Degraded, and Operationally-Limited Environments

These themes occur throughout the document, but one can’t call this a strategy. It does, however, qualify as guidance for shaping the policy of Air Force Space Command. But policy must not be mistaken for strategy. Any bureaucrat can make policy, but bureaucrats don’t fight and win wars.

Reconnect as Airmen and Embrace Airmindedness

Now “airmindedness” is an awkward neologism, but it does represent an attempt to represent the qualities needed for the “aerospace nation.” These qualities are difficult to define; this document defines them awkwardly (like its neologisms), but at least it makes an attempt to define them. That is to say, this document makes an attempt to define the distinctive institutional culture of the Air Force Space Command. There is a value in this effort. This is what, if anything, distinguishes the Air Force Space Command from the other branches of the armed services. The need to reconnect with the profession of arms and at the same time to foster the distinctive qualities necessary to aerospace operations, which means pushing the boundaries of technology, constitute a unique challenge for a large, bureaucratic institution (which is what the peacetime military is).

If I had written this I would emphasized the need to continually update and revise any conception of what it means to engage in aerospace operations, hence “airmindedness.” This document focuses on “airmindedness” by emphasizing “shared core values,” innovation, the self-image of the airman as a combatant, development of expertise, resilience capacity (which in this context seems to mean taking care of the individual airman), and supporting the families of airmen while the latter are deployed. While these are all admirable aims, even essential aims, it is astonishing how many of these strategic statements read like social science documents of a Carl Rogers person-centered kind. I would have aimed at conceptually surprising the target audience of this document so that they could see these challenges in a new light, rather than through the lens of boilerplate management-speak.

Preserve the Space and Cyberspace Environments for Future Generations

Strategically, this is perhaps the most important part of the document. In four admirably short paragraphs, this page systematically lays out the the large-scale vision of deterring the outbreak of war, or triumphing in the event that war breaks out. Here, finally, we have a strategy: free flow of commerce and information, deterring adventurism that would compromise the free flow of commerce and information, influencing international norms of behavior in order to deter adventurism, “dissuade and deter conflict” by fielding “forces and capabilities that deny our adversaries the ability to achieve their objectives by imposing costs and/or denying the benefits of hostile actions…” I would have put this section front and center in the document, and connected all the other themes to this central strategy.

Deliver Integrated Multi-Domain Combat Effects in, from and through Space and Cyberspace

This section of the document addresses the technological underpinnings of the strategy announced in the previous section, and so can be considered its tactical implementation on a technological level. Such an emphasis fits in well with the idea of “airmindedness” as a distinctively innovative approach to combat power. But hiding this on page 12 under a section title that is all but incomprehensible is not helpful. The reference to “agility of thought” is belied by the management-speak of the entire document. This agility of thought should extend to the conceptual formulation of what is being done, and how it is being presented.

Fight through Contested, Degraded and Operationally-Limited Environments

This section of the document specifies “four critical activities” that would allow the Air Force Space Command to fight in “Contested, Degraded and Operationally-Limited Environments.” In other words, this is the contemporary approach taken by Space Command to the perennial problem of warfighting that Clausewitz called the “fog of war” (“Nebel des Krieges” — Clausewitz himself used the term “friction,” but this has popularly come to be know as “fog of war”). The document defines these four critical activities intended to mitigate the fog of war as follows:

1. Train to threat scenarios — endeavor to discover the boundaries of our capabilities and constantly reassess those boundaries as threats and blue force capabilities evolve.

2. Identify the timelines and authorities required to successfully defend, fight, and provide effects in today’s and tomorrow’s environments with Operations Centers capable of executing them.

3. Establish the right authorities. For those authorities we control, push the right authorities as far down as possible to ensure timely response.

4. Establish and foster a joint, combined, and multidomain warrior culture that embraces pushing and breaking our operational boundaries and adapting and innovating new doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities, and policy (DOTMLPF-P) solutions.

The friction of combat environments is a real and serious problem for the contemporary technologically-sophisticated warfighting effort — perhaps more of a problem than in the pre-technological age of war. The most sophisticated uses of technology are networked, and sophisticated technology requires continual maintenance and repair. If the first thing that happens in the battlespace is for the network to fail, any battle plan based upon that network will have become irrelevant. How to take advantage of networked information flow while not being captive to the vulnerabilities of such a network is a central problem for warfighting in the technological era. In so far as the Air Force Space Command presents itself as being a uniquely technological capable and competent, this is perhaps the overwhelming challenge to this branch of the military.

Given the centrality of the problem, not surprisingly the document details another seven explicit steps toward attaining the goal of mitigating friction in the technological battlespace. Prefatory to these seven principles the document states, “Our Space Enterprise Vision will capture the key principles needed to guide how we will design and build a space architecture suitable for operations in a contested environment.” No doubt volumes of study have been devoted to this problem internally, and it is admirable that this has been condensed down into seven principles.

As this is intended to be strategic document, I would go a bit farther into the high concept aspect of this problem, and how it could be tackled on the strategic level. What we have seen in recent history is that domains of human endeavor (including warfighting) are utterly transformed when technology becomes cheap and widely available. Adversaries have used this fact asymmetrically against institutionalized armed forces. The strategic approach to being wrong-footed in this way, it seems to me, would be to turn precisely this emerging historical dynamic against asymmetrical forces exploiting this opportunity. How can this be done? A strategy is needed. None is enunciated.

You Make a Difference, Today and Tomorrow

The document closes with a directive to carefully re-read the document and to discuss and to think critically about carrying out the commander’s intent formulated in this statement of principles. There is even an assurance that those who act most fully and faithfully in carrying out this intent will not be punished or put their careers in jeopardy by getting too far out ahead. This observation points to the fundamental tension between the continuous innovation required to keep up with the pace of technological innovation and the inherent friction of any bureaucratic institution. This, too, like the problem of friction in the technological battlespace, is a central problem for the Air Force Space Command, and deserves close and careful study. The definitive strategy to address these two central problems has not yet been formulated.

If I had written this document, I would have had a one paragraph introduction from the general, put the last sections of crucial strategic content first, and reformulated the initial sections so that each section was shown to contribute to and to derive from the central strategic ideas. Beyond that, I would suggest that the institutional challenges faced by Air Force Space Command, recognized in the phase “agility of thought,” points to the need for continual conceptual innovation in parallel with continual technological innovation. The Air Force needs to hire some philosophers.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Hybrid Warfare

7 October 2014

Tuesday

Since the recent Russian incursion in east Ukraine I have been seeing the term “hybrid warfare” being used. I first encountered this in the Financial Times on Friday 29 August 2014 (“Russia’s New Art of War”), which shows how far behind the curve I am, as when I looked up the term I frequently found hybrid warfare referred to as a “buzzword” (and, until now, I had heard none of this buzz). There is already an anthology of essays on hybrid warfare, Hybrid Warfare: Fighting Complex Opponents from the Ancient World to the Present, edited by Williamson Murray and Peter R. Mansoor, which takes a primarily historical perspective and focuses on hybrid warfare as the combination of conventional and irregular forces employed in tandem. In any case, here is how the FT article characterized hybrid warfare:

“The phrase refers to a broad range of hostile actions, of which military force is only a small part, that are invariably executed in concert as part of a flexible strategy with long-term objectives.”

The article also quotes General Valery Gerasimov, Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Federation, from an article that appeared in the Russian defense journal VPK, as follows:

“Methods of conflict,” he wrote, have changed, and now involve “the broad use of political, economic, informational, humanitarian and other non-military measures”. All of this, he said, could be supplemented by firing up the local populace as a fifth column and by “concealed” armed forces. Mr Gerasimov quoted the Soviet military theoretician Georgii Isserson: mobilisation does not occur after a war is declared, but “unnoticed, proceeds long before that.”

In the Times of Malta article about General Gerasimov’s appointment as Chief of Staff, Putin appoints a new army chief, Putin is quoted as saying, “new means of conducting warfare are appearing.” It would seem that Putin’s choice to head Russia’s military has taken it upon himself to formulate and refine these new means of conducting warfare, which may prove to be ideal for implementing the Putin Doctrine.

The Georgii Isserson mentioned in the above quote in the FT was a theoretician of “deep battle” (about which I wrote in Deep Battle and the Culture of War) and the author of two important treatises, The Evolution of Operational Art, 1932 and 1937, and Fundamentals of the Deep Operation, 1933. (The former has been translated into English and is available in PDF format.) Thus we see that Gerasimov is drawing on an established tradition of Russian strategic and tactical thought, and we might well ask, in an inquiry regarding hybrid warfare, if the latter constitutes the contemporary extrapolation of the Soviet conception of deep battle.

Isserson’s The Evolution of Operational Art is a highly ideological book, at the same time as being both a theoretical and practical military manual. Throughout the text he employs the language and the concepts of Marx, Engels, and Lenin in a way that is familiar from many Soviet-era books. While some Soviet-era texts following this pattern are a worthless Hodge-podge, fawning for Party approval, in the case of Isserson’s book, the intermingling of revolutionary communism and organized, large-scale military violence works quite well, and this is one of our first clues to understanding the nature of hybrid warfare. There is a continuum that extends from revolutionary violence to military violence, and it is not necessary to limit oneself to any one point on this continuum if one has the ability to act across the spectrum of operations.

A translation of the above-quoted article by General Gerasimov has been posted on Facebook by Robert Coalson (the original Russian text is also available). It is a work of great military insight, admirable in its analytical clarity. In this translation we read:

“The focus of applied methods of conflict has altered in the direction of the broad use of political, economic, informational, humanitarian, and other nonmilitary measures — applied in coordination with the protest potential of the population. All this is supplemented by military means of a concealed character, including carrying out actions of informational conflict and the actions of special-operations forces. The open use of forces — often under the guise of peacekeeping and crisis regulation — is resorted to only at a certain stage, primarily for the achievement of final success in the conflict.”

If the methods of warfare described by General Gerasimov are to be understood as the definitive statement — so far — of hybrid warfare, then we can see from his article that this is a highly comprehensive conception, but not merely eclectic. The general states that, “Frontal engagements of large formations of forces at the strategic and operational level are gradually becoming a thing of the past.” This is undoubtedly true. I have observed many times that there have been no peer-to-peer conflicts since the middle of the twentieth century, and none seem likely in the near future. So while hybrid warfare is a comprehensive conception, it is not about peer-to-peer conflict or frontal engagements of large formations. Hybrid warfare is, in a sense, about everything other than peer-to-peer frontal engagement. One might think of this as the culmination of the mobile small unit tactics predicted by Liddel-Hart and Heinz Guderian, practiced by the Germans with Blitzkrieg, and further refined throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, but I don’t want to too quickly or readily assimilate Gerasimov’s conception to these models of western military thought.

Gerasimov, true to the Russian concern for defense in depth (a conception that follows naturally from the perspective of a land empire with few borders defined by geographical obstacles), places Isserson’s concern for depth in the context of high-technology implementation, as though the idea were waiting for the proper means with which to put it into practice:

“Long-distance, contactless actions against the enemy are becoming the main means of achieving combat and operational goals. The defeat of the enemy’s objects is conducted throughout the entire depth of his territory. The differences between strategic, operational, and tactical levels, as well as between offensive and defensive operations, are being erased.”

The erasure of the distinction between offensive and defensive operations means the erasure of the distinction between defense in depth and offense in depth: the two become one. General Gerasimov also demonstrates that he has learned one of the most important lessons of war in industrial-technological civilization:

“A scornful attitude toward new ideas, to nonstandard approaches, to other points of view is unacceptable in military science. And it is even more unacceptable for practitioners to have this attitude toward science.”

Science and its applications lies at the root on industrial-technological warfare no less than at the root of industrial-technological civilization, both of which are locked in a co-evolutionary spiral. Not only does the scope of civilization correspond to the scope science, but the scope of war also corresponds to the scope of science. And not only the scope of science, but also its sophistication. If Gerasimov can imbue this spirit into the Russian general staff, he will make a permanent contribution to Russia military posture, and it is likely that the Chinese and other authoritarian states that look to Russia will learn the lesson as well.

That the idea of hybrid warfare has been given a definitive formulation by a Russian general, drawing upon Soviet strategy and tactics derived from revolutionary movements and partisan warfare, and that the Russian military has apparently implemented a paradigmatic hybrid war in east Ukraine, is significant. Even as a superpower, the Russians could not compete with US technology or US production; Soviet counter-measures were usually asymmetrical — and much cheaper than the high-technology weapons systems fielded by the US and NATO. Even as the US built a carrier fleet capable of dominating all the world’s oceans, the Soviets built supersonic missiles and supercavitating torpedoes that could neutralize a carrier at a fraction of the cost of a carrier. This principle of state-sponsored asymmetrical response to state-level threats is now, in hybrid warfare, extended across the range of materiel and operations.

How can hybrid warfare be defined? How does hybrid warfare differ from MOOTW? How does hybrid warfare differ from asymmetrical warfare? How does hybrid warfare differ from any competently executed grand strategy?

It is to Gerasimov’s credit that he poses radical questions about the nature of warfare in order to illuminate hybrid warfare, as when he asks, “What is modern war? What should the army be prepared for? How should it be armed?” We must ask radical questions in order to make radical conceptual breakthroughs. The most radical question in the philosophy of warfare is “What is war?” The article on war in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy characterizes war as follows:

‘War’ defined by Webster’s Dictionary is a state of open and declared, hostile armed conflict between states or nations, or a period of such conflict. This captures a particularly political-rationalistic account of war and warfare, i.e., that war needs to be explicitly declared and to be between states to be a war. We find Rousseau arguing this position: “War is constituted by a relation between things, and not between persons… War then is a relation, not between man and man, but between State and State…”

Any definition of war is going to incorporate presuppositions, but in asking radical questions about warfare we want to question our own presuppositions about war. This suggests the possibility of the via negativa. What is the opposite of war? Not peace, but non-war. What is non-war? That is a more difficult question to answer. Or, rather, it is a question that takes much longer to answer, because non-war is anything that is not war, so in so far as war is a limited conception, non-war is what set theorists call the complement of war: everything that a (narrow) definition of war says that war is not.

Each definition of war implies the possibility of its own negation, so that there are at least as many definitions of non-war as of war itself. Clausewitz wrote in one place that, “war is the continuation of politics by other means,” while in another place he wrote that war is, “an act of violence intended to compel our opponent to fulfill our will.” Each of these definitions of war can be negated to produce a definition of non-war, and each produces a distinct definition of non-war. The plurality of conceptions of war and non-war point to the polysemous character of hybrid warfare, which exists on the cusp of war and non-war.

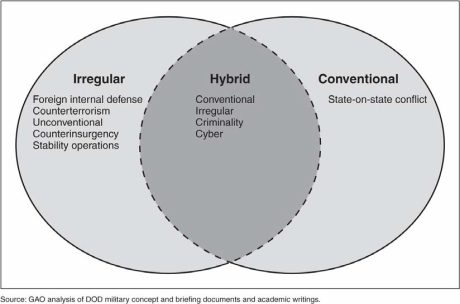

Although the US DOD declines to define hybrid warfare, NATO has defined hybrid threats as follows:

“A hybrid threat is one posed by any current or potential adversary, including state, non-state and terrorists, with the ability, whether demonstrated or likely, to simultaneously employ conventional and non conventional means adaptively, in pursuit of their objectives.”

NATO Military Working Group (Strategic Planning & Concepts), February 2010

Let us further consider the possible varieties of warfare in order to illuminate hybrid warfare by way of contrast and comparison. The following list of seventeen distinct forms of warfare recognized by the US DOD and NATO is taken from Hybrid Warfare: Briefing to the Subcommittee on Terrorism, Unconventional Threats and Capabilities, Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, by Davi M. D’Agostino (hybrid warfare is not on the list because it is not officially defined):

● Acoustic Warfare (DOD, NATO) Action involving the use of underwater acoustic energy to determine, exploit, reduce, or prevent hostile use of the underwater acoustic spectrum and actions which retain friendly use of the underwater acoustic spectrum.

● Antisubmarine Warfare Operations conducted with the intention of denying the enemy the effective use of submarines.

● Biological Warfare (DOD, NATO) Employment of biological agents to produce casualties in personnel or animals, or damage to plants or materiel; or defense against such employment.

● Chemical Warfare (DOD) All aspects of military operations involving the employment of lethal and incapacitating munitions/agents and the warning and protective measures associated with such offensive operations. Since riot control agents and herbicides are not considered to be chemical warfare agents, those two items will be referred to separately or under the broader term “chemical,” which will be used to include all types of chemical munitions/agents collectively.

● Directed-Energy Warfare (DOD) Military action involving the use of directed-energy weapons, devices, and countermeasures to either cause direct damage or destruction of enemy equipment, facilities, and personnel, or to determine, exploit, reduce, or prevent hostile use of the electromagnetic spectrum through damage, destruction, and disruption. It also includes actions taken to protect friendly equipment, facilities, and personnel and retain friendly use of the electromagnetic spectrum.

● Electronic Warfare (DOD) Military action involving the use of electromagnetic and directed energy to control the electromagnetic spectrum or to attack the enemy. Electronic warfare consists of three divisions: electronic attack, electronic protection, and electronic warfare support.

● Guerrilla Warfare (DOD, NATO) Military and paramilitary operations conducted in enemy-held or hostile territory by irregular, predominantly indigenous forces (also called Partisan Warfare).

● Irregular Warfare (DOD) A violent struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over the relevant population(s). Irregular warfare favors indirect and asymmetric approaches, though it may employ the full range of military and other capacities, in order to erode an adversary’s power, influence, and will.

● Mine Warfare (DOD) The strategic, operational, and tactical use of mines and mine countermeasures. Mine warfare is divided into two basic subdivisions: the laying of mines to degrade the enemy’s capabilities to wage land, air, and maritime warfare; and the countering of enemy-laid mines to permit friendly maneuver or use of selected land or sea areas. (Also called Land Mine Warfare)

● Multinational Warfare (DOD) Warfare conducted by forces of two or more nations, usually undertaken within the structure of a coalition or alliance.

● Naval Coastal Warfare (DOD) Coastal sea control, harbor defense, and port security, executed both in coastal areas outside the United States in support of national policy and in the United States as part of this Nation’s defense.

● Naval Expeditionary Warfare (DOD) Military operations mounted from the sea, usually on short notice, consisting of forward deployed, or rapidly deployable, self-sustaining naval forces tailored to achieve a clearly stated objective.

● Naval Special Warfare (DOD) A designated naval warfare specialty that conducts operations in the coastal, riverine, and maritime environments. Naval special warfare emphasizes small, flexible, mobile units operating under, on, and from the sea. These operations are characterized by stealth, speed, and precise, violent application of force.

● Nuclear Warfare (DOD, NATO) Warfare involving the employment of nuclear weapons (also called Atomic Warfare).

● Surface Warfare (DOD) That portion of maritime warfare in which operations are conducted to destroy or neutralize enemy naval surface forces and merchant vessels.

● Unconventional Warfare (DOD) A broad spectrum of military and paramilitary operations, normally of long duration, predominantly conducted through, with, or by indigenous or surrogate forces who are organized, trained, equipped, supported, and directed in varying degrees by an external source. It includes, but is not limited to, guerrilla warfare, subversion, sabotage, intelligence activities, and unconventional assisted recovery.

● Under Sea Warfare (DOD) Operations conducted to establish and maintain control of the underwater environment by denying an opposing force the effective use of underwater systems and weapons. It includes offensive and defensive submarine, antisubmarine, and mine warfare operations.

To each of these “officially” recognized types of warfare we can dialectically oppose a type of non-war or peace (the latter for ease of reference), as, e.g., “unconventional warfare” implies the possibility of “unconventional peace.” With so many varieties of warfare, it is inevitable that some of these categories will overlap with other categories of warfare, so that one particular species of peace may be another species of warfare, and vice versa. For example, one might be at “peace” in regard to a clearly delimited conception of “multinational warfare” while simultaneously being in a condition of open hostility in regard to an equally clearly delimited conception of “irregular warfare.”

One of the ways in which we might understand hybrid warfare is as accepting prima facie this diverse admixture of types of warfare that, in Wittgensteinian terms, overlap and intersect. Hybrid warfare, then, may consist of selectively, and at times simultaneously, pursuing (or avoiding) any and all possible forms of warfare across the spectrum of conflict.

Given the comprehensive scope of hybrid warfare, the resources of a major industrialized nation-state would be a necessary condition for waging hybrid warfare, and this clearly distinguishes hybrid warfare from irregular, partisan, or unconventional warfare in the narrow sense. Only the most successful and well-funded non-state entities could aspire to the range of operations implied by hybrid warfare, and in so far as one of the essential feature of hybrid warfare is the coordinated use of regular and irregular forces, a non-state entity without regular forces would not, by definition, be in a position of wage hybrid warfare. But it would be a mistake, as we can see, to get too caught up in definitions.

As we can see, trying to answer the question, “What is hybrid warfare?” (much less, “What is war?”) raises a host of questions that could only be dealt with adequately by a treatise of Clausewitzean length. Perhaps the next great work on the philosophy of war will come out of this milieu of hybrid conflict.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .