Developmental Temporality

6 January 2014

Monday

Time flies, as we say, and as it flies we develop temporally, passing through stages of time consciousness.

The Idea of Developmental Temporality

The idea of developmental temporality seems very simple to me, but I have learned from experience that the things I find to be intuitively obvious are anything but to others, in the same way that the ideas that others take for granted come slowly to me, and I often must pass through my own developmental process of misunderstanding another’s ideas in several different ways before I can begin to really focus on the intended meaning.

There are many theories of developmental psychology to describe the life of the individual, and there are also many theories of civilizational development to account for the life cycle of a civilization — though the theories of development applicable to entire civilizations are not usually conceived in developmental terms. There is, in fact, a reason that civilizations are not usually viewed in a developmental light, which is because it has become morally unacceptable in our time to make a distinction in the level of development of civilizations because this implies comparison, and comparisons among civilizations evoke the idea of colonialist paternalism. To speak of civilizations in developmental terms runs the risk of encountering moral outrage for ranking civilizations at a time when all civilizations are understood to be equal (though some are more equal than others).

Most well known among these theories of development are Piaget’s cognitive developmental stages, Erikson’s psychosocial developmental stages, and Vygotsky’s theory of zones of proximal development, all of which I have discussed in other contexts (cf., e.g., The Hierarchy of Perspective Taking). Piaget’s cognitive approach has come in for a lot of criticism because it focuses on intellectual development and does not concern itself with emotional or social development. Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development still have a bit of currency, though many more sophisticated theories have refined the work of Piaget, Erikson, and Vygotsky.

I don’t know of anyone who has formulated a developmental psychology of time-consciousness, although such a schema is implicit in Husserl’s phenomenology of time consciousness and in other accounts of time and history. (I cite Husserl because it is his account of time that has most influenced me.) The idea of developmental temporality is that our time consciousness, like our intellect, our emotions, our social life, and other aspects of the individual personality, passes through stages of development, and given that the temporality of social wholes emerges from shared temporality, the temporality of social wholes also undergoes a developmental process (cf. The Origins of Time).

Time consciousness at its greatest extent passes imperceptibly into historical consciousness, which is an extension and expansion of time consciousness; there is no absolute distinction between time consciousness and historical consciousness. It would be possible to write a minute-by-minute history of a single day (some works of literature are famous for this technique) so that a period of time within the scope of human time consciousness is treated in terms of historical consciousness. This relationship between time consciousness and historical consciousness is not strictly symmetrical, since there are limits to the extent to which we can expand time consciousness, and the longest spans of time studied by scientific historiography — the time scales of biology, geology, and cosmology — cannot equally well be treated in temporal and historical terms.

The Seven Ages of Man (‘As You Like It’, Act II Scene 7), 1838,

William Mulready, born 1786 – died 1863

Ontogenetic Developmental Temporality

The time consciousness of the individual unfolds as ontogenetic developmental temporality. How are we to understand the temporal development of the individual? There are many ways to do this, but I will start with Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s famous evocation of the seven ages of man, which comes from the “All the world’s a stage” monologue from the play As You Like It. Here, in the language of the first folio edition, is the monologue:

All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women, meerely Players; They haue their Exits and their Entrances, And one man in his time playes many parts, His Acts being seuen ages. At first the Infant, Mewling, and puking in the Nurses armes: Then, the whining Schoole-boy with his Satchell And shining morning face, creeping like snaile Vnwillingly to schoole. And then the Louer, Sighing like Furnace, with a wofull ballad Made to his Mistresse eye-brow. Then, a Soldier, Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the Pard, Ielous in honor, sodaine, and quicke in quarrell, Seeking the bubble Reputation Euen in the Canons mouth: And then, the Iustice In faire round belly, with good Capon lin’d, With eyes seuere, and beard of formall cut, Full of wise sawes, and moderne instances, And so he playes his part. The sixt age shifts Into the leane and slipper’d Pantaloone, With spectacles on nose, and pouch on side, His youthfull hose well sau’d, a world too wide, For his shrunke shanke, and his bigge manly voice, Turning againe toward childish trebble pipes, And whistles in his sound. Last Scene of all, That ends this strange euentfull historie, Is second childishnesse, and meere obliuion, Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans euery thing.

Taking Shakespeare’s seven ages of man as a convenient point of departure, let us consider each in turn as a stage in the development of historico-temporal consciousness:

● Mewling infant The time consciousness of the infant is confined to the immediately present moment; here time consciousness extends over several seconds, and at most over several minutes.

● whining Schoole-boy With the development of personal autonomy, the individual transcends the immediacy of the moment and begins to be conscious of lengths of time from minutes through hours to days. The whining school-boy hates to go to school because his captivity within the walls of a school for a few hours seems interminable, and the idea of summer seems like an impossibly distant future.

● Sighing lover The signing lover expands his temporality not only diachronically, but also synchronically, and his perception of time expands into a social community. The object of his love is understood to be possessed of a similar temporality to himself, and those impediments to their being together become temporal agents in their own right.

● Bearded soldier In a man’s productive years, whether as soldier or farmer or whatever trade he has taken up, time consciousness necessarily expands to the seasons of the year, and the round of activities appropriate not only to each day, but also to each season, is forced upon the awareness of the individual, and this life according to the seasons eventually expands to comprise years.

● Severe justice The severe justice, the man of the community who takes seriously his role in maintaining the order of his social milieu, finds his historico-temporal conscious expanded to comprise the cycles of years experienced in the growth on cities and industry, the business cycle, and rise and fall of families and their fortunes, and the larger engagements of states and empires that must be counted in years and decades.

● Lean Pantaloon It is only in later life, when the immediate needs of self and family and community have been served that the individual begins to look to his legacy and begins to think in terms of his place within a multi-generational time scale. Although the “pantaloon” is a figure of fun from commedia dell’arte, concerned almost exclusively with money but often fooled and the butt of jokes, the pantoloon figure does rightly indicate a concern for the long-term investment of capital, which is one function of multi-generational thinking. Outside the schematic world of commedia dell’arte, the man who has survived into old age with his intellectual faculties intact plans not for the morrow, or even for the decade, but for generations, and perhaps for centuries. The monuments he sponsors and the legacy that he endows he desires to be a perennial contribution to the ages, and not merely a passing fancy of the present, which latter may have contented him in earlier life.

● Second childhood The deterioration of mental faculties returns the individual to a second childhood, and in this second childhood the individual’s time-consciousness is incrementally reduced to that of the infant — a consciousness of the present moment only, mewling and puking in his nurse’s arms.

This above account of the development of individual time consciousness is only a first rough sketch, and should in no sense be considered definitive or exhaustive. There is much work to be done on ontogenetic temporal consciousness.

Phylogenetic Developmental Temporality

The time consciousness of social milieux unfolds as phylogenetic developmental temporality. How are we to understand the historico-temporal development of the social wholes? I have several times employed a tripartite division of human history between pre-civilized nomadic hunter-gatherers, agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, and industrial-technological civilization. I will take this schemata and divide each of these stages in two yielding six stages of social development in human communities. These communities experience the development of historico-temporal consciousness as follows:

● Early Nomadic-Foraging Societies In the earliest nomadic-forager societies life was continuous with the prehuman past and communal time-consciousness was primarily restricted to the immediate present. This is the infancy of historical consciousness, bounded by the length of a day.

● Late Nomadic-Foraging Societies Once a uniquely human modus vivendi was established, building on newly available cognitive capacities, a fully articulated hunter-gather society emerged in which communal time-consciousness embraced an awareness of annual seasons, and planning looked forward to this annual cycle, anticipating, for each biome, the necessary preparations for ongoing survival for a given biological context. Such preparations in temperate climates often became a form of transhumance when a social group migrated twice a year between winter and summer encampments. This particular period of human development corresponded with the climatological period of melting glaciers with the beginning of the current interglacial period and onset of the Holocene, so that each year offered a steadily warmer climate and the opening up of further lands freed from glaciation.

● Early Agrarian-Ecclesiastical Civilization With the advent of civilization in the most extended sense of that term, comprising organized settled agricultural societies and their urban centers, planning for the future becomes systematic. Agricultural production is linked to climatological and astronomical cycles, and time-consciousness expands beyond that annual cycle to become historical consciousness in an explicit form for the first time in human history. Early imperial states — Egyptian Kingdoms, Sumeria, Akkadia, Assyria, etc. — record the dynasties of their kings and begin to keep chronicles and histories of human events.

● Late Agrarian-Ecclesiastical Civilization From approximately the Axial Age to the Industrial Revolution, agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization consolidates its institutions in increasingly mature and technically sophisticated ways, including its institutions of time keeping, calendrics, and rational planning for the future of social institutions. These efforts are, however, hampered by conceptual and technological limitations.

● Early Industrial-Technological Civilization The violent break with the agricultural past that resulted from the industrial revolution meant a slight setback for historical consciousness, but to a certain extent, this setback was necessary, because the largest historico-temporal context industrial-technological civilization had available was a pre-industrial mythological account of the world dating to the Axial Age, which many heroically sought to apply to the changed human circumstances of the post-industrial world, though all such attempts have either been failures or have been maintained only at the cost of bad faith (i.e., Sartrean self-deception). The means of industrial-technological civilization directly addressed those conceptual and technological limitations that held back the development of historico-temporal consciousness in the previous level of social development. the advent of scientific historiography extended concepts of time to geological, biological, and cosmological scales that no human being had previously conceived. The dialectic of the pressing immediacy of industrial society and the newly expanded time scales of scientific historiography has resulted in an incompletely resolved tension; he have yet to fully contextualize the 24/7 world of industrial society into its biological and cosmological place in nature. It is at this juncture that we stand today.

● Late Industrial-Technological Civilization The next level of historical consciousness will be to fully integrate industrial-technological civilization into the time scales conceptualized in scientific historiography, and to understand ourselves and our civilization in this historical context.

As with the stages of individual time consciousness outlined above, this attempt at a schema of civilizational development is in no way definitive or exhaustive, though it is a little more systematic than the series of stages taken from Shakespeare. I also would not want a developmental account of civilization to be understood as the necessary or inevitable path to development of a civilization. In future work I hope to show the possibility of many different forms of civilization that would have been possible but were never realized — what I have elsewhere called Counterfactual Conditionals of the Industrial Revolution.

The Future of Developmental Temporality

A collapse of our civilization into some subsequent ruination (i.e., the realization of an existential risk) may well lead, as in the case of the second childhood of ontogenetic developmental temporality, to the level of historico-temporal consciousness found in early nomadic-forager societies, in which the scope of time-consciousness has contracted to that of the immediate needs of the immediate present, and the struggle to live has become so challenging that there remains no remaining intellectual capacity to place human activity within a larger time scale. In such a scenario we would take no thought for the morrow. Of such individuals in such a state it could be rightly said:

“Man, that is born of a woman, hath but a short time to live, and is full of misery. He cometh up, and is cut down, like a flower; he fleeth as it were a shadow, and never continueth in one stay.”

On the other hand, the continued existential viability of our civilization would yield further expansions in the scope of historico-temporal consicousness. In the event of transhumanist extensions of individual lifespans by several orders of magnitude, individual consciousness may reach an intimate and personal familiarity with historical periods of time denied to the three-score-and-ten of our current biological embodiment. We may, then, pass beyond Shakespeare’s seven ages and establish new ages of ontogenetic developmental consciousness that embrace larger spans of time, even as our science is defining scales of time beyond those known today. Thus there remains much scope yet for historico-temporal consciousness, which would address, to a certain degree, the asymmetry mentioned above between historical consciousness and temporal conscious. This asymmtry, and the possibilities of further development, suggest many lines of research.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Diachronic Extrapolation and Uniformitarianism

25 March 2013

Monday

In my last post, The Problem with Diachronic Extrapolation, I attempted to show how diachronic extrapolation, while the most familiar form of futurism, is often misleading because it fails to adequately account for synchronic interactions as a diachronic strategic trend develops. In other posts concerned with unintended consequences I have emphasized that, in the long term, unintended consequences often outweigh intended consequences. Unintended consequences are the result of synchronic interactions that were not foreseen, that were no part of diachronic agency, and those cases in which unintended consequences swamp intended consequences the synchronic interactions have proved more decisive in shaping the future than diachronic causality.

In my post on The Problem with Diachronic Extrapolation I made several assertions that clearly imply the limitation of inferences from the present to the future, which also implies the limitation of inferences from the present to the past. This brings up issues that go far beyond futurism.

In that post I wrote:

“…diachrony over significant periods of time cannot be pursued in isolation, since any diachronic extrapolation will interact with changed conditions over time, and this interaction will eventually come to constitute the consequences as must as the original trend diachronically extrapolated.”

…and…

“…the most frequent form of failed futurism is to take a trend in the present and to project it into the future, but any futurism worthy of the name must understand events in both their synchronic and diachronic context; isolation from succession in time is just as invidious as isolation from interaction across time…”

The reader may have noticed the resemblance of this species of failed futurism to uniformitarianism: instead of taking a strategic trend acting at present and extrapolating it into the future, uniformitarianism takes a physical force acting in the present and extrapolates it into the future (or, as is more likely the case in geology, into the past). This idea of uniformitarianism is usually expressed as, “the present is key to the past,” and we might similarly express the parallel form of futurism as being, “the present is key to the future.” These two claims — the present is the key to the past and the present is the key to the future — are logically equivalent since, as I pointed out previously, every present is the future of some past, and the past of some future.

Since these interpretations of uniformitarianism involve uniformity across past and future, these formulations closely resemble formulations of induction also stated in terms of past and future, as when the logical problem of induction is formulated, “Will the future be like the past?” It is at this point that the philosophy of time, the philosophy of history, the philosophy of science, and futurism all coincide, because it concerns a problem that all have in common.

Stephen Jay Gould noticed this similarity of uniformitarianism and induction in his first published paper, “Is uniformitarianism necessary?” Gould, of course, become famous for his critique of uniformitarianism, and for this alternative to it, punctuated equilibrium (for which he shares the credit with Niles Eldredge). In this early paper by Gould, Gould distinguished between substantive uniformitarianism and methodological uniformitarianism. He tried to show that the former is simply false, and the the latter, methodological uniformitarianism, is now subsumed under the scientificity of geology and paleontology. Here is now Gould put it:

“…we see that methodological uniformitarianism amounts to an affirmation of induction and simplicity. But since these principles belong to the modern definition of empirical science in general, uniformitarianism is subsumed in the simple statement: ‘geology is a science’. By specifically invoking methodological uniformitarianism, we do little more than affirm that induction is procedurally valid in geology.”

Stephen Jay Gould, “Is uniformitarianism necessary?” American Journal of Science, Vol. 263, March 1965, p. 227

That is to say, the earth sciences use the scientific method, which Gould characterizes in terms of inductive logic and the principle of parsimony (I would argue that Gould is also assuming methodological naturalism) — therefore everything that is worth saving in uniformitarianism is already secured by the scientific status of geology, and therefore uniformitarianism is dispensable. Having once served an important function in science, uniformitarianism has now, Gould contends, become an obstacle to progress.

As I noted above, Gould didn’t merely assert that uniformitarianism was no longer necessary, but devoted his career to arguing for an alternative, punctuated equilibrium, which asserts that long period of stasis are interrupted by catastrophic discontinuities. While much has been written about uniformitarianism vs. punctuated equilibrium, I see this as the thin end of the wedge for considering all kinds of alternatives to strict uniformitarianism, and to his end I think we would do well to explore all possible patterns of development, whether uniform (slow, gradual, incremental), punctuated (sudden, catastrophic, discontinuous), or otherwise.

Of course, we could easily produce more sophisticated formulations of uniformitarianism that would avoid the subsequent problems that have been raised, but this is the path that leads to Ptolemaic epicycles and attempts to “save the appearances,” whereas what we want is a rich mixture of theoretical innovation from which we can try many different models and select for further development those that are most true to the world.

Since the philosophy of time, the philosophy of history, the philosophy of science, and futurism all coincide at the point represented by the problem of the relationship of parts of time to other parts of time (and the idea of temporal parts is itself philosophical contested), all of these disciplines stand to learn something of value from exploring alternatives to uniformitarianism. In so far as futurism is dominated by nomothetic diachrony, and constitutes a kind of historical uniformitarianism, very different forms of futurism might emerge from a careful study of the alternatives to uniformitarianism, or merely from a recognition that, as Gould put, uniformitarianism is no longer necessary and something of an anachronism. If there is anything of which futurists ought to beware, being an anachronism must be close to the top of the list.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Origins of Time

30 November 2011

Wednesday

The Construction of Ecological Temporality

A Genetic Account of the Origins of the World

The ontogeny of time

The emergence and development of temporal consciousness — that is to say, the origins of individual time, the ontogeny of time — begins in the individual, but the early experience of the individual is that of an individual embedded in a temporal context. The individual’s internal time consciousness is constructed in a temporal context that I will call the reflexive experience of time.

Children — at least those children allowed a childhood, which is not always the case — live most in the world of meso-temporality, mostly because they have not yet learned not to trust, and so they feel free to express the spontaneity of their inner time consciousness as though by reflex. Reflexive experience of time, in which there are few if any barriers between the micro-temporality of the individual and the meso-temporality of the immediate social context of the individual, embodies an absolute innocence.

In a condition of innocence, everything that occurs is new, so that time is densely populated with unprecedented events. Every hour and every day brings novelty. As we age, every hour and every day brings more of the same — the same old same old, as we say today — and so it is little surprise that we don’t notice the passing of this undifferentiated sameness. For the young, time flies by unnoticed, and because the passage of time is unnoticed it has the quality of timelessness.

Later, in our maturity, we have the ability to appreciate episodes of innocence that we could not have appreciated in our younger years — thus following the well-worn idea that youth is wasted upon the young — there is another sense in which youthful experience makes the fullest use of time and yields a density of experience that we cannot experience in later life.

The time consciousness of youth, driven by the stream of novelty that is the result of innocence, sharpens and enlarges the smallest events, and thus we see young children sobbing over a ice cream cone that has dropped to the ground, which leaves us, as adults, largely unmoved. We shrug our shoulders and move on. Would that we could experience life with such intensity that an ice cream cone were worth a flood of tears.

There is a sense in which it is counter-intuitive to speak of the intensity of experience of children, since the halcyon days of youth are usually not thought to consist of intensity but rather of carefree indolence, but in the sense outlined above, the innocent lead lives of greater intensity than the jaded.

Innocence wrings every last drop from the passing of time, so that in a condition of innocence there is no moment that is wasted. In maturity, the greater part of time is wasted, until, as Shakespeare noted, having wasted time, time wastes us.

Developmental temporality: the role of play

Developmental psychologists have had much to say about the child’s initial encounters with a recalcitrant world that does not answer to its whims. This initial phase of socialization is also the first loss of innocence, and the first compromise of reflexive temporality. As the consciousness of temporality progresses in the individual, the individual comes to understand that they can cultivate a Cartesian privacy in which fantasies will not be interrupted by the recalcitrant world. Thus reflexive temporality gradually gives way to imaginative temporality, and the spontaneity of the child is displaced from the immediate expression of inner promptings to the inner expression of these promptings by way of imagination. Thus play emerges, and the imaginative temporality of play allows the individual to further develop the inner time consciousness of Cartesian privacy.

Play, however, also makes possible a re-discover of reflexive temporality when the childred discovers other children and begins to play with them. The shared, social temporality of play, especially when adults are not present to puncture the illusions generated by imaginative time consciousness, can again converge onto a purely reflexive time consciousness when the child feels free to express their spontaneity among peers who share the form of time consciousness common to this stage in the development of childhood.

Pieter Bruegel, detail from Children's Games, 1560, Oil on oak panel, 118 x 161 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Vienna

Play, too, is eventually compromised, as conflicts inevitably emerge from games played with peers, so that the life of the child exhibits a dialectic of shifting between reflexive time consciousness and imaginative time consciousness, which is a shift of the focus of spontaneity from outer life to inner life and back again to outer life. It is the dialectical process that contributes to the further development and reinforcement of an inner time consciousness of Cartesian privacy, which becomes a haven for the individual, wounded by encounters with an unsympathetic world.

Games among children often result in conflicts, and these conflicts teach us early in life that the world is usually not responsive to our will.

All throughout the dialectic of early time consciousness, however, the experience of the child is still marked by innocence, and it is the process of the degradation of innocence that brings about a fully mature time consciousness (if, in fact, this does develop, and its development is not arrested by trauma).

The degradation of innocence and the emergence of mature time consciousness

The degradation of innocence comes about from cumulative experience. Cumulative experience can only be experienced as cumulative with the development of memory, so that the emergence of robust memories is central to the emergence of fully mature time consciousness. However, it is the same process of the emergence of memory that degrades innocence. Memory demonstrates to us the non-novelty of our spontaneity, and as the spontaneity of our internal promptings loses its novelty, it also begins to lose its interest.

As we age, and the depth and breadth of our experience grows, preserved in an improving memory, and our opportunities for experiences of innocence decline proportionately until our capacity approaches zero and we no longer expect or even hope to directly experience innocence again. In the lives of many adults it is their relationships with children that yield whatever vicarious experiences of innocence for which they still retain hope, and so they take pleasure in seeing the world anew through the eyes of another, but there is a melancholy to this because one knows in one’s heart of hearts (as subtle as the distinction may seem to be) that there is a difference between immediate and vicarious experiences of innocence.

And yet (and despite), when we are surprised by an authentic experience of innocence later in life, beyond the bounds of youth, we now experience it from a perspective of maturity, and both its rarity and our capacity to appreciate it make the experience all the more precious. When we are young, everything is new to us, and experiences of innocence are common; experience narrows the scope of innocence until any such experience appears as something completely unexpected, but when it does occur we have the maturity to appreciate the experience that we did not possess in youth.

It is the same innocence that is behind the very different time consciousness of youth compared to maturity. Everyone knows that as you age, time seems to pass ever more quickly, until it flies by and the years scarcely make any impression in their passing. This stands in stark contrast to feelings of endless summers from our childhood that seemed to go on forever, as well as anticipating and waiting for holidays that seemed to take forever to arrive.

The time consciousness we associate will full cognitive modernity is a product of cognitive maturity.

Keeping secrets and Cartesian privacy

Another aspect of the child’s encounter with a recalcitrant world not obedient to his or her wishes is the discovery of the power of secrets. The youngest children, immersed as they are in meso-temporality and observing few if any boundaries between internal spontaneity and external expression, cannot keep a secret. Even if they make an experiment of it, and older children try to let them in on a secret, they will usually blurt it out, and as a consequence are considered untrustworthy. …

The shared confidences of older children, however, especially confidences that exclude adults and their alien forms of time consciousness, become an object of envy for the younger child, who wants to become “grown up” in order to share in these confidences. Thus the younger child makes a conscious effort of will to cultivate inhibitions on his or her spontaneity. Older children will continue to test the younger children for the trustworthiness in keeping secrets, at the behest of the pleading of younger children, initially with small secrets and eventually with larger secrets. When these secrets are successfully kept, the child passes the test, and in passing the tests passes another threshold of maturing time consciousness.

The experimenting and testing of secret-keeping trains the child in the development of his or her Cartesian privacy, which becomes a faculty consciously developed by the individual as an exclusively private reserve from which the world entire. The child discovers that not only may adults be excluded, but that other children can also be excluded from this realm of Cartesian privacy. In this perfectly private space of conscious, purely interior micro-temporal consciousness takes root and begins to grow, and as it grows it contributes progessively more to constitution of individual consciousness.

Shared time, social time, and the world as we find it

One of the most mysterious aspects of personal chemistry between individuals, and that which is perhaps the conditio sine qua non of friendship (whether Platonic or romantic), is the simple fact of shared time. Friendship has its origins in childhood play, but its possibilities are deepened by mature time consciousness. We are able to be friends with those with whom the common passage of time is enjoyable. Play is the first expression of joy in shared time. In adolescence, the shared time begins to take on a more intellectual form as shared time becomes primarily shared conversation. In contemporary colloquial English, this is called “hanging out” or simply “hanging.”

I suspect that everyone, or almost everyone, has experienced among their interaction with acquaintances the fact that, with some combinations of individuals, the two or more parties in question mutually enjoy the passage of time together, while among other combinations of individuals, the two or more parties find the common passing of time together to be irritating, unpleasant, or otherwise unfulfilling. The former is a welcome kind of chemistry, while the latter is an unwelcome (but also inevitable) kind of chemistry.

There are also obvious cases of asymmetry, when one party to the shared passage of time finds the experience rewarding, while another party to the same shared temporal frame of reference finds the experience unrewarding or even odious. Here the temporal frame of reference is identical, but the subjective experience of that shared time is sharply distinct. Such are what Shakespeare called the pangs of despised love.

In my post ecological temporality, in which I developed Urie Bronfenbrenner’s bio-ecological model, specifically expanding and extending the ecological treatment of time, I distinguished levels of temporality parallel to Bronfenbrenner’s distinction between levels of bio-ecology. Thus what Husserl called internal time consciousness I called micro-temporality, and the interaction of micro-temporalities begets meso-temporality.

Meso-temporality is social time, and another way to refer to social time would be to call it shared time. An isolated individual experiences the micro-temporality of internal time consciousness, and simply by being present in an environment experiences a rudimentary level of meso-temporality from the necessary interaction of an organism with its environment (the minimal form of rudimentary meso-temporality involves interaction with an inert environment, as, for example, knocking on a door).

Shared time is facilitated by secret-keeping. The young child who cannot yet keep a secret says things openly that impair social relationships. As children learn more above the social environment in which they find themselves, they learn, under penalty of social exclusion, what must be confined to Cartesian privacy, and what may be openly and freely shared. To blurt out socially inappropriate assertions with no concern for boundaries of privacy — both one’s own privacy as well as the privacy of The Other — is to commit a social faux pas and to risk social exclusion. Being envious of social inclusion, children make an effort to train themselves in the boundaries of polite expression, and in so doing they are forced to cultivate a consciousness of the Cartesian privacy of The Other, which is another important threshold on the way to mature time consciousness. The recognize the Cartesian privacy of the other is to recognize the internal time consciousness of The Other. Thus one’s own emerging micro-temporality is placed in the context of the other’s inferred micro-temporality, which together and jointly constitute social time.

The social time or meso-temporality that emerges from a common temporal frame of reference for two or more individuals possessing internal time consciousness is perhaps distinct from that meso-temporality emergent from the micro-temporality of internal time consciousness in the context of an inert, non-conscious environment. Thus meso-temporality may take a variety of forms. Meso-temporality simpliciter may be taken as the interaction of a micro-temporal agent with its environment. When that environment includes other micro-temporal agents and agents join in common action (or common inaction, for that matter), this is social time or share time. Thus social time is a subdivision of meso-temporality.

The minimum condition for social time is two conscious individuals. Two micro-temporalities functioning in a common frame of temporal reference constitutes the first and simplest level of shared time, though shared time can be augmented with the addition of more conscious individuals and can grow until, for spatio-geographical reasons, a common frame of temporal reference is not longer possible. This meso-temporality that exceeds a common frame of temporality is meso-temporality of a higher order of magnitude, and thus constitutes exo-temporality. The interaction of meso-temporalities yields exo-temporality, which is the usually setting for “history” as this is usually understood. Herodotus and Thucydides write on the level of exo-temporality: the interaction and intersection of particular communities over space (a given geographical region) and time (a given period of history).

Returning to the interaction of micro- and meso-temporalities, we can see from the very different responses that individuals have to shared social time that this “functionality” in a shared temporal frame of reference can function in different ways for different individuals. Even when the shared temporal frame of reference is identical, the micro-temporality of consciousness usually remains clearly distinct from the shared time. That is to say, consciousness usually enjoys Cartesian privacy. This is the point of departure of Husserlian internal time consciousness.

The exceptions to Cartesian privacy occur when an individual agent, even having previously cultivated a sense of Cartesian privacy in the childhood dialectic of reflexive time and imaginative time (which perhaps only becomes possible in the context of fully mature historical consciousness), becomes so fully embedded in a meso-temporal frame of reference that they experience no boundaries between themselves and the other agents present. In shared social time one may be so comfortable in the presence of others that one is as spontaneous in interacting with them as one may be spontaneous with one’s own thoughts in private. This constitutes a (temporary) recovery of the reflexive time consciousness of early childhood.

One way to express this is that a particular subdivision of shared social time is when individuals participating in a common meso-temporal frame of reference experience in common what psychologists call “flow states”, such that the individuals in question can no longer distinguish between their internal time consciousness and the meso-temporality of shared time: the barriers of the self come down, and the individual is lost in the shared world. This would be a particularly intimate form of social time, and is possibly the necessary condition of love. Possibly.

The lost paradise of reflexive time

Why do we seek ideal love? We seek ideal love because it is the temporary recovery of the lost paradise of the purely reflexive temporality — unmindful of boundaries, unmindful of a distinction between self and world, unmindful of any barrier to absolute spontaneity and freedom of expression, unmindful of any social constraint risking social exclusion. Love is the reminder of what we have lost in coming to mature time consciousness, even while knowing what we having gained in terms of cultivated micro-temporality, memory linked both to immediate micro-temporality and enduring self-identity, and an awareness of history and our personal place within history.

Moreover, ideal love in the context of mature time consciousness can exceed or surpass the lost paradise of early childhood’s reflexive temporality, because ideal love can accommodate an authentic awareness of the beloved as other, as possessing its own Cartesian privacy and its own micro-temporality. To love the other in full awareness of their otherness is a more profound species of shared social temporality, and with this profundity comes depth of feeling that did not exist and could not exist in childhood. It has been said that a woman’s heart is a ocean of secrets, and perhaps we need not even superadd a qualification of gender to this poetic truth. Shared secrets, withheld from the rest of the world, can be among the most powerful form of shared social temporality, and it is the power of these experiences that moves us (i.e., we experience the sublime) and thus generates profound awareness of the other and depth of feeling in one’s relationship to The Other.

However, love disappoints more often than it satisfies, so that our tentative reaching out to the world in search of love becomes an experiment that is disconfirmed more often than it is confirmed. And even when love satisfies, it rarely endures. Some retreat within themselves, when the pangs of despised love are too powerful, while others, unable to forget the ideal of the lost paradise, continue to seek, and are in rare moments rewarded for their efforts.

The phylogeny of time

The origin of non-human time, of objective time, is the proper concern of the phylogeny of time. Of course, ontogeny and phylogeny are intimately interconnected, and we may even speculate on a temporal recapitulation in which temporal ontogeny recapitulates temporal phylogeny, but I will not pursue this further in the present context.

In terms of the origins of time, or, rather the origins of human time consciousness, interaction with other agents within an environment — i.e., meso-temporality — almost certainly preceded the emergence of self-aware micro-temporality, just as meso-temporal interaction almost certainly preceded those larger temporal formations such as exo-temporality and macro-temporality.

Macro-temporality emerges even later, in terms of specifically human macro-temorality. Before humanity knew itself as a whole (on which cf. the quote from George Friedman that I cited in Humanity as One) we did not know ourselves as a whole either in space or time. It is only with the emergence of human self-knowledge of our species as a whole in time that macro-temporality emerges, and this cannot happen until a fully naturalistic account of human origins emerges with Darwin.

The internal time consciousness of Cartesian privacy emerges from cognitive modernity, much as does historical consciousness. There is a sense in which internal time consciousness is historical consciousness of the self, while historical consciousness is the internal time consciousness of history. Both represent temporal consciousness of a greater order of magnitude than the interactions of meso-temporality. This is another interesting idea that I will not pursue further at present, but which deserves independent exposition.

Cosmological and relativistic time

Objective conceptions of time rooted in mathematics, physics, cosmology, and the natural sciences can be formulated without reference to human time, much less to the structures of micro- and meso-temporality that constitute the greater part of the ordinary business of life. However, science, as a human undertaking, retains its relevance to the human agents who are responsible for the constitute of objective, natural time.

In fact, we run into difficulties when we attempt to formulate a doctrine of time too far removed from human experience, precisely because human experience has been responsible for science, and the truths of science must ultimately be redeemed in human experience.

One is immediately put in mind, in this context, of Newton’s famous formulation from his Principia:

“Absolute, true, and mathematical time, of itself, and from its own nature, flows equably without relation to anything external, and by another name is called duration: relative, apparent, and common time, is some sensible and external (whether accurate or unequable) measure of duration by the means of motion, which is commonly used instead of true time; such as an hour, a day, a month, a year.”

Newton implies that human measures of time such as “an hour, a day, a month, a year,” are untrue, because only mathematical time is true time, but Newton’s categories of “relative, apparent, and common time,” are in fact quantitative measures of time in natural history which can be studied and defined with the utmost precision by natural science. Time measurements of a day, a month, and a year are rooted in astronomical events that constitute some of humanity’s first and earliest scientific knowledge. Had Newton gone in the other direction in the litany of apparent time, listing instead “an hour, a minute, a second, …” he would have approached the punctiform present and therefore the ideal limit of micro-temporality.

Despite the relativity of simultaneity that isolates us from the temporality of other dynamic systems independent of our own, there is a sense in which human temporal categories seem to me to retain their relevance throughout the cosmos today — at very least, just because human beings are an interested party in the universe at present — in a way that I do not feel human temporal categories to be relevant to very early cosmological history or to the far flung future of cosmological history.

One way to formulate this would be to put it in the context of the divisions of cosmological history propounded in The Five Ages of the Universe. We live today in the Stelliferous Era, i.e., the Age of Stars. Before the Stelliferous Era came the Primordial Era, which includes the Big Bang, expansion, inflation, and consists in large part of subatomic particles that have not yet congealed into familiar elements and structures. After the Stelliferous Era come the Degenerate Era, the Black Hole Era, and the Dark Era, after the stars have burned themselves out and the cosmos goes dark again. This is a classic scenario of cosmological eschatology based on heat death due to entropy.

Human measures of time seem meaningless at the quantum and subatomic scale of the early universe, and these same measures seem equally meaningless at the vast time scales of the universe as it steadily runs down in entropic heat death. Yet, at the present, anthropocentric time scales seem relevant to the universe entire as we know it today (relevant, though not by any means necessary or even privileged), although most of the universe is beyond any meaningful relation to specifically human time, and will remain so.

One justification for the feeling (which I readily admit is my own prejudiced intuition, and I claim no validity for it beyond that) that anthropocentric temporal categories apply throughout the Stelliferous Era is that life as we know it is possible throughout the Stelliferous Era, while life as we know it is not possible during the Primordial Era or during the Degenerate Era or after.

The possibility of life as we know it throughout the Stelliferous Era means the possibility of other species emergent from other solar systems, other planets, other biospheres, and other sentient species emergent from a parallel biological context, functioning according to the same natural laws that govern our world, our bodies, and our minds, means that an approximately anthropocentric (although technically xenocentric) time consciousness exists elsewhere in the Stelliferous Era, and is perhaps pervasive throughout it.

Objective micro-temporality

Although the categories of human time seem irrelevant to either the earliest stages of the universe immediately following the big bang, and perhaps also to the largest structures of space andtime, the “cosmic soup” of the early universe is recognizably a form of micro-temporality, even if it is not microtemporality at the same level of human micro-temporality. Moreover, the micro-temporality of pre- and sub-atomic particles prior to the precipitation of universe from the coalescence of ordinary elements is another paradigmatic instance of meso-temporality: the particles interact, and they can only come together and coalesce into the world we know and love by coming together.

The temporality of the early universe thus closely parallels the temporality of the ontogeny of time in the individual, in so far as the individual’s micro-temporality is always constituted jointly by the meso-temporality of the shared milieu in which the individual finds himself or herself. The micro-temporality of the individual particles of the early cosmic soup is crucially dependent upon the milieu of interacting particles, which is a meso-temporal milieu.

Larger structures of cosmological time — objective exo-temporality, objective macro-temporality, and objective metaphysical temporality — only come above in the fullness of time — lots of time — as the universe matures and new spatio-temporal structures emerge. As novel physical structures emerge, there necessarily emerges an interaction of these larger structures with smaller structures and with other larger structures, and these interactions of ever-increasing size produce the higher levels of objective ecological temporality.

Closing speculation

As ever-larger temporal structures emerge from a universe consolidating its structure, and ever-larger temporal structures emerge from the maturation of human consciousness, these objective and human forms of ecological temporality converge. It would be very difficult to demonstrate a close parallelism between the micro-temporality of consciousness and the micro-temporality of fundamental particles, but in the increasingly more comprehensive temporal categories of ecological temporality the chasm between the two becomes less marked.

At the level of macro-temporality, it is not difficult to see the convergence of human time and objective time, since human life and human civilizations are shaped by macroscopic forces such as geography, and geography is a local expression of cosmology. A human civilization that emerges from its planet-bound condition and asserts itself on a cosmological scale would constitute human beings living on a macro-historical level, and to do so would demand the emergence and cultivation of macro-temporal consciousness.

It may be only at the level of metaphysical temporality (which I also call metaphysical history) that there can be a full convergence of human time and objective time, so that that two ultimately become indistinguishable and therefore one. This may be the ultimate telos of civilization: to establish an identity with the universe at large.

. . . . .

I have had a little more to say on the above in Addendum on the Origins of Time.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

…

Ecological Temporality

23 March 2011

Wednesday

How swiftly Time before my eyes rushed on

After the guiding Sun, that never rests,

I will not say: ‘twould be beyond my power.

As in a single moment did I see

Ice and the rose, great cold and burning heat

A wondrous thing, indeed, even to hear.

Francesco Petrarch, Triumph of Time (TRIUMPHUS TEMPORIS, from Petrarch’s Trionfi)

Metaphysical preamble on Ecological Ontology

Recently in Integral Ecology I began to formulate an extended conception of ecology that was indebted to Urie Bronfenbrenner’s bio-ecological model of social interconnectedness, though intended to go beyond both the biological and social scope. Yesterday in Metaphysical Ecology I explained why I will discontinue my use of the terms “integral history” and “integral ecology” in favor of metaphysical history and metaphysical ecology. Ultimately, this is the more appropriate terminology for what is, at bottom, a philosophical project of seeing the world whole.

Metaphysical ecology is nothing but the extension of the concept of ecology until it coincides with ontology. This yields an ontology founded in scientific empiricism and methodological naturalism.

To define metaphysical ecology as “nothing but…” is what logicians call an “extremal clause,” the purpose of which is to put an end to any further elaboration of a definition (usually stated in recursive form) and to confine ourselves only to that which has been stipulated. Such definitions are often thought to be reductivist. Reductivist definitions are not necessarily a bad thing. When we define water as H2O we are reducing the macroscopic features of ordinary experience in order to account for water as a chemical molecule understood in the context of atomic theory. Many reductive definitions are like this, giving us more theoretically powerful formulations because they are contextualized within an established and more comprehensive theory.

Reductive definitions, however, have a deservedly bad reputation because of the misuse and abuse to which they have been put. When we say that “x is nothing but y” we are doing an obvious disservice to the true nature of x. Consider such statements as, “Pinocchio was nothing but a puppet” or “Hamlet is nothing but a play” and you will understand what I am getting at. However, in the present case of defining metaphysical ecology in terms of ontology we really have not introduced any unwarranted or arbitrary limitations into the concept of ecology since ontology is the most comprehensive philosophical category.

There is a sense in which it is ironic to even consider time in an ontological context, as ontology has been anti-temporal almost from its beginnings to the present day. Traditional Western metaphysics pursued the tradition of setting up a distinction between appearance and reality, and, in its most traditional forms, would consign time, the temporal, and the ephemeral to the sphere of mere appearance. It is to the credit of contemporary analytical metaphysics, seeking as it does to exemplify the spirit of scientific naturalism, has reconciled itself with the reality of time, so that the main stream of Anglo-American analytical philosophy is as concerned to produce an adequate metaphysical theory of time as it is concerned with any other feature of the world.

While I have noted previously (in The Apotheosis of Metaphysics) that contemporary object oriented ontology reinstates the traditional distinction between appearance and reality in an especially elaborate and robust form, the larger philosophical trend until just recently, both on the continent (in the form of phenomenology) and in the analytical tradition (in the form of phenomenalism and empiricism) was the collapse of the distinction between appearance and reality and the simultaneous attempt to formulate a unified account of the world. it could be argued that the distinction between appearance and reality is more fundamental than the doctrine of the unreality of time, since if the distinction is denied there is no category of appearance to which time is to be consigned.

In any case, ecological temporality as I attempt to formulate it below is probably consistent with either the retention or the denial of the distinction between appearance and reality, and thus could even be seen as being consistent with the doctrine of the denial of the reality of time, in so far as ecological temporality can be given an exposition as mere appearance. However, in spirit, my ambition for ecological temporality is that it should be understood as science extrapolated to the limits of philosophical thought, and therefore constituting a naturalism that sees no need for anything beyond the world of naturalism, and therefore no need for a distinction between appearance and reality.

From Ecological Systems Theory to Metaphysical Ecology

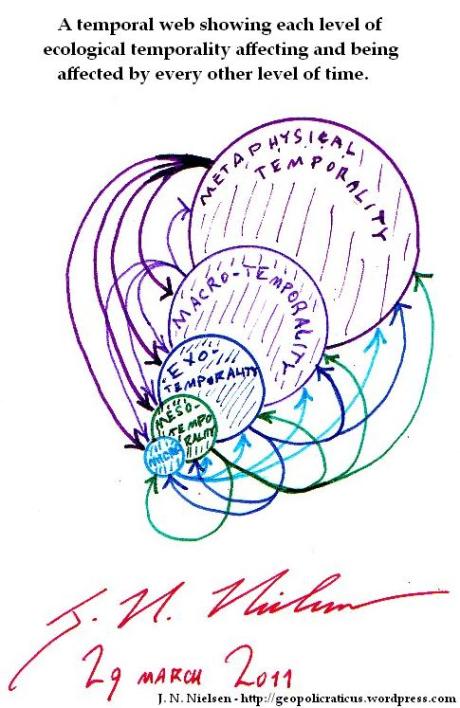

As noted above, I began my exposition of metaphysical ecology in my post Integral Ecology. There I began with Bronfenbrenner’s ecological distinction between micro-systems, meso-systems, exo-systems, macro-systems, and chronosystem. The last of these, the chronosystem, is shown in the following illustration as an additional “halo” surrounding the nested bio-ecological levels centered around the individual person.

I think that Bronfenbrenner’s treatment of the chronosystem was inadequate, radically so, and his treatment of ecological levels could be improved, so, building on his bio-ecological model, and also separating time into its own hierarchy from micro-system to macro-system and beyond, I reformulated metaphysical ecology and metaphysical temporality as shown below.

Here is my revised version of the ecological hierarchy:

● The Micro-system: The setting in which the individual lives.

● The Meso-system: Relations between microsystems or connections between contexts.

● The Exosystem: Links between a social setting in which the individual does not have an active role and the individual’s immediate context.

● The Macrosystem: The culture in which individuals live.

● Metaphysical Ecology (or metaphysical system): Ultimately, the metaphysical level of the ecological system as the furthest extrapolation of bio-ecology is co-extensive with metaphysical history. This is the master category and the most comprehensive form of bio-ecological thought, just as metaphysical history is the master category of history and the most comprehensive form of historical thought.

And after having separated Bronfenbrenner’s chronosystem from the ecological hierarchy and extrapolated the chronosystem on its own, here is my formulation of a ecological hierarchy for time, or a temporal ecology, if you will:

● Micro-temporality: The temporal setting in which the individual lives.

● Meso-temporality: Relations between micro-temporalities or connections between temporal contexts.

● Exo-temporality: Links between a temporal setting in which the individual does not have an active role and the individual’s immediate temporal context.

● Macro-temporality: The historical era in which individuals live.

● Metaphysical temporality: The whole of metaphysical history in which the individual and other lesser temporalities (Meso-temporality, Exo-temporality, and Macro-temporality) are embedded.

While the illustration of Bronfenbrenner’s chronosystem as an additional concentric level is accurate in so far as it goes, it doesn’t go far enough. It is accurate because everything within the ecological systems is subject to time, and therefore to show time (i.e., the chronosystem) as embracing all the ecological levels is accurate. However, each level of ecological structure is subject to each level of time. Here is an illustration of how each level of the ecological systems are ultimately subject to metaphysical time:

The same kind of illustration could be drawn to show how all levels of ecology are subject to micro-temporalities, meso-temporalities, exo-temporalities, and macro-temporalities. It would require a rather large illustration to show all the possibilities, so I have put them in the chart form below.

Metaphysical ecology and metaphysical temporality (or, if you like, what I have been calling integral history, but which I will now call metaphysical history) stand in a systematic relationship to each other. Better, they stand in an ecological relationship to each other. Firstly, however, the systematic relationship: each level of metaphysical ecology can be given an exposition at each level of metaphysical temporality. This means that there are twenty-five possible perspectives on the interaction between metaphysical ecology and metaphysical temporality. I have diagrammed these possibilities in the chart below.

In the technical terminology of the theory of relations, the blue circles on the left are the domain, the gray circles on the right are the range, and the both together are the field of the relation. A diagram that traces all possibilities of field of the relation is confusing to the eye (being a little too complex to have immediate appeal to geometrical intuition), so it might be better understood by considering a simpler diagram of a subset of the field of relations between one term in the domain to the several terms of the range. Here is a diagram that shows only the relations of a single micro-system of ecology to the levels of temporality:

If we take the single term from the domain to be a person, the person’s relation to micro-temporality is what Husserl called internal time-consciousness (one’s relation to oneself), the relation to meso-temporality is the individual’s relation to inter-subjectivity (the social world of which we are a part, and the venerable philosophical question of other minds), the relation to exo-temporality is the individual’s relation to temporal systems of which he is not an immediate participant (e.g., what’s happening on the other side of the planet, or in the Andromeda Galaxy, which could be given an exposition in terms of the relativity of simultaneity), the relation to macro-temporality is the individual’s relation to the historical era of which he is a (temporal) part (e.g., one’s place today in the history of industrialized civilization), and the relation to metaphysical temporality is the individual’s place in the whole of metaphysical history (one’s place in the world from the beginning of time to the present). Each of these permutations can be extrapolated from each term in the domain to each of the terms in the range.

A convenient way to express these relationships would be to refer to the terms of the domain with a capital “S” with a subscript to indicate the ecological level (Smic, Smes, Sexo, Smac, and Sint), and similarly to refer to the terms of the range with a capital “T” followed by a subscript to indicate the temporal level (Tmic, Tmes, Texo, Tmac, and Tint). In this way each of the twenty-five permutations in the upper diagram can be expressed, for example, like this: Smic/Tmic, which is the topmost line in both diagrams. However, a more intuitive way to express the relationships between metaphysical ecology and metaphysical temporality would be to join the two at the level of the individual, which is the microsystem in common, and then to represent their possible relationships as a graph:

This makes the unity of micro-systems — ecological and temporal — obvious, but gives the impression that metaphysical ecology and metaphysical temporality diverge, though, as I wrote above, they coincide very much as micro-systems coincide. I could say that these schematic delineations of metaphysical ecology and metaphysical temporality (or metaphysical history, if you prefer) are alternative formulations of the same state of affairs. Metaphysical ecology and metaphysical history coincide; the difference between the two is only the perspective one takes on the whole field of ecology. Metaphysical ecology approaches ecological structures structurally and synchronically (one could even say, to preserve even greater symmetry, that metaphysical ecology approaches temporal structures synchronically); metaphysical history approaches the same ecological structures functionally and diachronically.

The point of taking an ecological perspective, however, is not to reduce matters to their smallest and simplest terms, or to erect hierarchies and classification schemas, but to see things whole. It is my purpose, in so far as it is possible, to see time whole, and that means all parts of time related to all other parts of time, and, in the spirit of the observation above that metaphysical ecology and metaphysical history are alternative formations of the same state of affairs, to see the several parts of time in relation to all other temporal-ecological structures and vice versa.

There is an ecology of time itself, an interrelationship of the various parts of time to the whole. As the ecological perspective in biology seeks to demonstrate by way of science the perennial mystical insight of the connectedness of all things (called panarchy in ecology), so too an ecology of time understands the connectedness of all times, of all moments to other moments, and of all moments of time to the whole of time. The ecological perspective provides us with a conceptual structure in which these relations of connectedness can be systematically delineated.

Once time is understood ecologically, one can bring this ecological temporality to a systematic understanding of ecology itself. We have seen that ecology has been defined as the science of the struggle for existence. This struggle takes place in time, and it takes place on many ecological levels simultaneously.

It would be counter-productive to attempt to pluck one paradigm of biological competition out the “levels of selection” controversy and to defend this at the expense of other paradigmata of selection. The world is a complex place in which almost also logical distinctions are muddied in practice. Thus selection is not one thing, but many things taking place over different ecological levels and also at different temporal levels. There is selection at the level of the genome, and therefore selfish genes, but there is also selection at the level of the individual, and at the level of the community and its niche, and at the level of the population and its biome, and ultimately on levels that transcend life and reach up to the life cycles of the stars — galactic ecology (or, as I would prefer, cosmological ecology, which converges on metaphysical ecology).

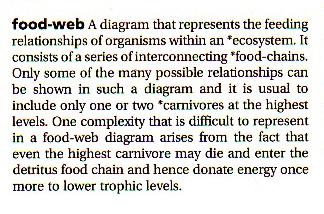

The generalization of ecology to metaphysical ecology demands that we also generalize those biological concepts that constitute ecology. One of these concepts to be generalized is that of a trophic layer. Biology online defines trophic as follows:

Trophic

Definition

adjective

(1) Of, relating to, or pertaining to nutrition.

(2) Of, or involving, the feeding habits or food relationship of different organisms in a food chain.

Trophic layers are thus layers, i.e., stratifications, of feeding relationships. We know that the primary relationship in nature, red in tooth and claw, is that of feeding. Biological ontology is a system of relationships based on feeding. In nature, one can eat or be eaten. Most likely, one with both eat and be eaten in turn. When big fishes eat little fishes, and the little fishes eat even smaller fishes, we call this a food chain. Here is how the Oxford Dictionary of Ecology defines food chain:

However, feeding relationships rarely constitute a simple linear chain, so ecologists have also defined a food web. Here is how the Oxford Dictionary of Biology defines a food web:

In the conceptually extended context of metaphysical ecology, rather than trophic layers, food chains, and food webs, I will instead posit metaphysical trophisms, ontic chains, and ontic webs. In Integral Ecology I observed that in the extended sense of (what I know call) metaphysical ecology, man does not live by bread alone. What this means in a metaphysical context is the human relationships, while not independent of feeding relationships, transcend feeding relationships and also include other kinds of relationships.

Metaphysical trophisms may sound difficult and abstruse, but it is really quite simple. What we have here is nothing but Plato’s famous definition of being: to be is the power to affect or be affected in turn. One way to affect or be affected is to eat or be eaten. These special cases of the Platonic definition of being define food chains and food webs, and these in turn define trophic layers. In the extended conception of metaphysical ecology we return to the abstract generality of the Platonic formulation, so that the power to affect and to be affected are the relationships of ontic chains and ontic webs, which taken together defined metaphysical trophisms.

I am not going to even attempt at present an exposition of metaphysical trophisms. Suffice it to say for the moment that metaphysical trophisms offer the possibility of an extremely fine-grained account of the world, but this possibility can only be redeemed through a fairly exhaustive treatment of a novel form of fundamentum divisionis significantly more complex than categories. Trophisms are more complex than categories because there are many different ways in which one object can affect or be affected by another, and each of these ways can be explicated exclusively in terms of the agent, or exclusively in terms of the sufferant, or in terms of the reciprocity of agent and sufferant.

What I would like to touch on at present, to give an initial sense of ecological temporality and its potential for conceptual clarification, are what we may call time chains and time webs, in parallel with the food chains and food webs of ecology in the strict and narrow sense of the term. Temporal chains and temporal webs are special cases of what I above called ontic chains and ontic webs, which are features of a more general ontological conception.

Micro-temporalities in relation to themselves and in relation to other micro-temporalities; taken together, interacting, they constitute meso-temporality.

When we consider some of the traditional philosophical conceptions of time (as well as intuitive conceptions of time), we can see that they fall into readily recognizable patterns that can be analyzed in terms of ecological temporality. For example, Husserl’s emphasis upon subjective time consciousness (and I should point out that I am in no way critical of this emphasis) is clearly what could be called a “bottom up” time chain, such that the whole structure of temporality, from the largest structures of metaphysical history down to the smallest structures of micro-temporality, are ultimately driven by (and presumably reducible to, thus constituting a reductive definition) the mind’s temporality.

Augustine (whom Husserl cited in his Cartesian Meditations) also reduced time to the perspective of the individual, though with the superadded metaphysical doctrine that time itself is unreal and has no ultimate place in the structure of the world. What this means in terms of ecological temporality is that the whole structure of metaphysical time is mere appearance erected upon the experiences of the individual. (Odd, is it not, then, that Augustine should be equally famous for his philosophy of history as given exposition in his City of God?) Augustine’s classic exposition of time is in Book XI of his Confessions, where Augustine writes in Chapters XXVII and XXVIII:

It is in you, O mind of mine, that I measure the periods of time. Do not shout me down that it exists [objectively]; do not overwhelm yourself with the turbulent flood of your impressions. In you, as I have said, I measure the periods of time. I measure as time present the impression that things make on you as they pass by and what remains after they have passed by–I do not measure the things themselves which have passed by and left their impression on you. This is what I measure when I measure periods of time. Either, then, these are the periods of time or else I do not measure time at all.

What are we doing when we measure silence, and say that this silence has lasted as long as that voice lasts? Do we not project our thought to the measure of a sound, as if it were then sounding, so that we can say something concerning the intervals of silence in a given span of time? For, even when both the voice and the tongue are still, we review–in thought–poems and verses, and discourse of various kinds or various measures of motions, and we specify their time spans–how long this is in relation to that–just as if we were speaking them aloud. If anyone wishes to utter a prolonged sound, and if, in forethought, he has decided how long it should be, that man has already in silence gone through a span of time, and committed his sound to memory. Thus he begins to speak and his voice sounds until it reaches the predetermined end. It has truly sounded and will go on sounding. But what is already finished has already sounded and what remains will still sound. Thus it passes on, until the present intention carries the future over into the past. The past increases by the diminution of the future until by the consumption of all the future all is past.

But how is the future diminished or consumed when it does not yet exist? Or how does the past, which exists no longer, increase, unless it is that in the mind in which all this happens there are three functions? For the mind expects, it attends, and it remembers; so that what it expects passes into what it remembers by way of what it attends to. Who denies that future things do not exist as yet? But still there is already in the mind the expectation of things still future. And who denies that past things now exist no longer? Still there is in the mind the memory of things past. Who denies that time present has no length, since it passes away in a moment? Yet, our attention has a continuity and it is through this that what is present may proceed to become absent. Therefore, future time, which is nonexistent, is not long; but “a long future” is “a long expectation of the future.” Nor is time past, which is now no longer, long; a “long past” is “a long memory of the past.”

I am about to repeat a psalm that I know. Before I begin, my attention encompasses the whole, but once I have begun, as much of it as becomes past while I speak is still stretched out in my memory. The span of my action is divided between my memory, which contains what I have repeated, and my expectation, which contains what I am about to repeat. Yet my attention is continually present with me, and through it what was future is carried over so that it becomes past. The more this is done and repeated, the more the memory is enlarged–and expectation is shortened–until the whole expectation is exhausted. Then the whole action is ended and passed into memory. And what takes place in the entire psalm takes place also in each individual part of it and in each individual syllable. This also holds in the even longer action of which that psalm is only a portion. The same holds in the whole life of man, of which all the actions of men are parts. The same holds in the whole age of the sons of men, of which all the lives of men are parts.

Thus does Augustine “explain away” time, but, at the same time, attributes time to the human mind, and so commits himself to a “bottom up” theory of time. While I find Augustine’s theory of time to be inadequate, it is at least more of a theory than Plato had, and in the context of platonism it accomplishes all that a theory of time could hope to accomplish even while declaring time to be ultimately unreal.

Saint Augustine asked 'What then is time?' and acknowledged that he could not answer the question. But, as Wittgenstein has pointed out, some things that cannot be said nevertheless can be shown.

The obvious antithetical view to the “bottom up” time chain is the “top down” time chain in which it is posited that all time in the world, at all ecological levels, follows from the over-arching structure of time which imposes its nature and character upon all subordinate temporalities, so that time and change are imposed from above rather than rising from below.

Plato, whom Augustine followed so closely in so many matters, including his denial of the ultimate reality of time, provides a perfect illustration of a philosophical “top down” time chain. Although for Plato there is no metaphysical temporality but only metaphysical eternity, such that the former is illusory appearance while the latter is reality, in one famous passage Plato wrote that, “time is the moving image of eternity.” Thus, for Plato, the over-arching reality of eternity trickles down into the interstices of the world, the appearance of time penetrating down from above.

Plato implicitly invoked a top-down model of time by making eternity generative of time; eternity is the Platonic form, while time in the mere image of eternity in the cave of shadows. For Plato, time and eternity are related as appearance to reality.

There is, furthermore, an intuitive correlate to this Platonic conception of time as the moving image of eternity, and this is the familiar sense in which people invoke Fate or Destiny as implacable temporal forces from on high that direct the lives of men below. This is famously expressed by Hamlet when the Prince of Denmark says, “There’s a Diuinity that shapes our ends, Rough-hew them how we will.” (Act V, scene ii) And all of the familiar mythological images, from the Fates and Furies of Greek tragedy to the Norns of Norse mythology, when the gods decides the fates of men ultimately powerless to shape their own destinies, represent a strongly top down model of temporal ecology.

The three norns: one to spin the thread of life, another to mark its length, and a third to cut the thread.

Top-down time chains are also common in contemporary scientific thinking and especially in cosmology. Some theorists of time as an expression of increasing entropy (the thermodynamic arrow of time) and the expansion of the universe (the cosmological arrow of time) come close to saying (without actually making it explicit) that if entropy could be reversed or if the universe halted in its expansion and then began to contract that time itself would reverse and subjective internal time consciousness would also reverse. However, it is much more common among scientists simply to pretend that subjective time consciousness doesn’t exist, or, if it does exist, that it isn’t important — perhaps it is a mere “user illusion.” Because of the distaste for philosophy, and especially for metaphysics, among scientists and most others wedded to methodological naturalism, thinkers of this stripe rarely bother to assert that subjective and internal time consciousness is unreal in the same way that their opposite numbers assert the unreality of cosmic time, but in effect the positions are perfectly symmetrical. The scientific denial of subjective time (and hence temporal chains driven from the bottom up by individual time consciousness) is an implicit assertion of the unreality of internal time consciousness.

An explicitly top-down model of time from John G. Cramer's paper, “Velocity Reversal and the Arrows of Time”