Why are US militant proxies ineffective?

23 October 2015

Friday

Some Lessons from Ineffective Interventions

Nation-states and other mainstream political entities often find their policy options constrained by public opinion, legal limitations, treaty obligations, and the moral scruples of individual leaders, and so in order to act with fewer constraints they cultivate relationships with militant groups that can act as proxies and which can take on missions that the regular forces of a nation-state cannot be tasked to accomplish. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union supported an array of militant proxies by identifying their struggle with global communist revolution and so exapting local struggles as new theaters for the Cold War, and they did this very effectively. At the present time, Iran has proved itself masterful in the use of militant proxies to affect outcomes throughout its sphere of influence, even as its economy has suffered from international sanctions. One can only admire this bravura performance, especially in comparison to the lackluster US efforts to mobilize militant proxies. What is it about the US political process that has meant that the militant proxies selected by the US have been largely ineffective?

Mullah Mohammad Omar eventually led forces once sponsored by the US against the US in a stunning reversal in post-Soviet Afghanistan.

The relation between a militant proxy and its state sponsor is what we would today call a “mutually beneficial relationship.” The relationship to a militant proxy with military objectives that are politically unacceptable (especially for a democracy) grants plausible deniability to the sponsor, who can then act with fewer constraints from behind a veil of secrecy, and it provides resources for the militant group. However, the relationship is often a troubled one. Militant proxies are often extraordinarily difficult to control and constrain, even when a state sponsor of such a proxy can pull the plug on its funding. It was said that Mullah Mohammad Omar was a, “rigid man who defied even his patrons.” While the Taliban were not properly a military proxy organization, the precursors of the Taliban functioned as US militant proxies employed against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, and constituted one of the few successes for the US in proxy warfare — though this success came at a great cost. The description of Mullah Omar by his Pakistani “handlers” prophetically fits the profile of an unmanageable proxy.

Most militant proxies do not view themselves as proxies, but as stand-alone militant groups with their own ends, aims, objectives, and motivations. If a state sponsor gives them arms, matériel, supplies, training, and advisers, such groups rarely feel beholden by these sponsors. Should the sponsor object to its other objectives or its methods, the attitude of the militant proxy is often the equivalent of a shoulder shrug and and a dismissive, “Let them fund the revolution.” There is nothing more commonplace in geopolitics that a nation-state patron of a militant proxy believing itself to be in control of a situation, only to discover that it cannot force the cooperation of its militant proxy at a sensitive political moment. And if a militant proxy can make itself strong enough through the temporary receipt of aid from a state sponsor, it can accept this aid in a pure spirit of cynical opportunism, making the calculation that once the aid is cut off due to lack of cooperation of the militant proxy with the sponsor state’s agenda, the group can then function on its own.

Perhaps the most well-known and effective militant proxy of our time is Hezbollah, which runs a virtual state-within-a-state in Lebanon, controlling much of the county, its politics, and a considerable geographical region. Hezbollah has long been one of the most effective and efficient militant proxies for Iran, and until recently also acted as a militant proxy of Syria; Syria was a crucial conduit for Iranian aid to reach Hezbollah in Lebanon. However, since Syria’s descent into civil war, Hezbollah has acted on behalf of the Syrian government as an agent in the internal struggle, rather than as an instrument of external force projection. That is to say, Hezbollah has proved itself such an effective fighting force that it not only defends its own interests, but now returns to defend the interests of its former sponsor, now under duress and in need of sponsorship itself.

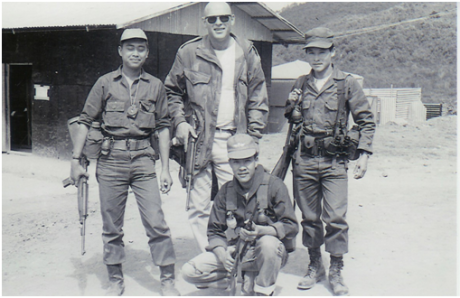

During the Vietnam war, the CIA virtually created a militant proxy from Hmong tribesmen. Because the US could not openly operate in Laos, a militant proxy was the weapon of choice to expand the war against Vietnam’s communists to the Pathet Lao communists in Laos. By most accounts the Hmong were effective fighters, but they were the military equivalent of astroturf: not grass roots, but essentially created by the CIA for US purposes. As long as the money flowed to pay and supply the fighters, they fought. The Hmong, then, turned out to be ineffective not because they couldn’t fight, but because they were more mercenaries than militant proxies. There is an interesting lesson in this observation: a truly effective militant proxy should have its own agenda, but, as we have already seen, recalcitrant proxies can be dangerous, and so there must be a balance between the militant agenda and the sponsor’s agenda.

A chaplain leads a group of Contra troops in a prayer at their base camp, Honduras, 1983. The Contras refer to the loosely organized groups of Nicaraguan rebels (who were at least partially supported by the US government through the Central Intelligence Agency) who militarily opposed to the success of the socialist Sandinista political party in Nicaragua in the late 1970s and 1980s. (Photo by Steven Clevenger/Getty Images)

After the US withdrawal from Indochina, Cold War proxy wars came closer to US shores as a number of guerrilla wars were fought in Central America, with the US backing a number of militant proxies in the region, most famously the Nicaraguan Contras, who fought against the Sandinista government of Nicaragua. The Contras did manage to disrupt the region, but they mounted few effective military operations, and no decisive operations. One would have thought, what with US resources flowing into a conflict so close to its borders, that it would have created a truly formidable militant proxy. This did not happen. In Latin America, militant proxies both communist and anti-communist became deeply involved in the drug trade in order to finance their operations. There is another important lesson to be learned from this failure: personal greed often trumps ideological fervor, and if the head of a militant proxy sees an opportunity to transform himself into a drug lord, he may well do so.

In the war in Iraq to unseat Saddam Hussein, with the Kurdish Peshmerga, the US had, in a rare instance, partnered with a militant proxy that really could deliver the goods. The Kurds fought effectively and seemed to possess the right balance between serving their own ends by serving the agenda of a sponsor. If the US had promised the Kurds a state of their own in exchange for an effective settlement of the conflict in Kurdish lands (or, perhaps I should say, the aspirational map of Kurdish sovereignty), it is highly likely that this could have been achieved. And by “a state of their own” I mean a real de jure nation-state, and not the de facto state the Kurds now possess. But the US is a world power, and the use of US power to guarantee a Kurdish state would have offended too many US allies. The overall strategic goals of the US and the Kurds were and are incompatible. Almost certainly both the US and the Kurds knew from the beginning that their alignment had to be temporary.

The Kurds were recently in the news again largely as a result of this photograph of a Kurdish woman identified as Rehana, sometimes known as the Angel of Kobane.

The Kurds have been in the news again lately because they have proved themselves among the few regional forces that have been combat effective against ISIS, and because of a particularly compelling photograph of a female Kurdish fighter that became briefly famous on the internet. However, the temporary and effective convergence of interests between the US and the Kurds was not fully exploited and the moment for this has probably passed.

In the tumult and confusion of regional instability in Mesopotamia, the US is now supporting the Free Syrian Army in Syria. Unfortunately, the Free Syrian Army is not making progress, but they have said the kind of things that US political leaders like to hear, and so they receive support. This is the “strategy” for Syria, but Syria cannot be treated in isolation from the rest of the region.

We can no longer speak of a US strategy in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria, because these states are nation-states in name only. The facts on the ground belie the official maps and the seats for delegates to the UN. We must speak of US policy regionally, apart from any hollowed-out and ineffective nation-state; and regionally, it must be said, US strategy has been a catastrophic failure. Worse yet, the US is continuing old and repeatedly failed policies, as though the situation on the ground can be rescued and turned around if the US will simply keep doing what it has been doing. In other words, the US is digging itself in deeper by the day.

One of the problems in Mesopotamia and the Levant is the failure of the US to support effective militant proxies, and its willingness to support ineffective militant proxies, so that even as it is spending money and political capital on forces that cannot win, it is not spending these same resources that could win if given the chance. Thus the US is experiencing an opportunity cost in the region with profound consequences. If the US supported the Kurds instead of the Free Syrian Army it might actually accomplish something, but this apparently comes with unacceptable political costs — as though the costs of failure could more easily be borne.

The bottom line is that US militant proxies are selected for ideological reasons rather than for reasons of combat effectiveness or shared military objectives. This is a disastrous mistake. Trying to select winners on the battlefield is a lot like a nation-state attempting to choose winners in the marketplace: states are notoriously bad at picking winners, and when they attempt to use the power they possess as a nation-state to enforce their choice (i.e., when they try to turn a loser into a winner by the methods available to nation-states) they usually fail. Not only that, they fail at great cost.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Hearts and Minds

21 December 2013

Saturday

“…what could be more excusable than violence to bring about the triumph of the cause of oppressed right?”

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, translated by Gerald E. Bevan, Part 2, Chapter 4

How are hearts and minds to be won? And how are they lost? These are questions that have become central to the practice of war in our time. In an age of declining peer-to-peer conflict the military environment is increasingly that of asymmetrical warfare, and there is a tension in the environment of asymmetrical warfare between the methods necessary to wage and to win a counter-insurgency and the methods necessary to win the hearts and minds of the people for whom insurgents claim to be waging an armed struggle.

Not only do we live in an age of declining peer-to-peer conflict and increasing asymmetrical warfare, but we also live in of age of popular sovereignty. In an age of unquestioned popular sovereignty, winning the hearts and minds of the people (or losing them) has not only immediate practical consequences but also far-reaching political and ideological ramifications that cannot be ignored. Terrorism today cannot be cleanly separated from insurgency, and insurgency cannot be cleanly separated from the ideal of national self-determination and popular sovereignty. Popular sovereignty means that the hearts and minds of the people rule the state, so that winning or losing hearts and minds is the difference between decreasing or increasing incidents of terrorism. Thus the question of hearts and minds becomes a question of terrorism.

Terrorism — especially terrorism occurring in the context of an insurgency — is one of the great security issues of our time, and the causes and motivations of terrorism constitute one of the great sociological problems of our time. Why do people commit acts of terrorism? What do they hope to gain by the use of terror? Who becomes a terrorist? How do terrorists understand their actions, and how are these actions understood by others? (Some of my earliest blog posts here were concerned with the subject of terrorism — The Future of Terrorism and Terrorism and the evolution of technology — as I had at that time recently read Caleb Carr’s Lessons of Terror — and I have continued to occasionally post on terrorism, as in The Apotheosis of Terrorism.)

The self-understanding and self-justification of the terrorism typically takes the form of an elaborate and detailed extremist ideology, and this extremist ideology is usually found in the context of a broader ideological tradition, of which the violent militant’s faction is a refined and carefully crafted set of beliefs that hangs together coherently and provides an explanation for all things, including the necessity of terrorism and militancy. Often, but not always, this extremist ideology is a set of religious beliefs specific to a particular religious community, in which the ethnic and social community is indistinguishable from the ideological community; in other words, there is an identification of a people with a set of beliefs that define this people. Not all of the people within this community may assent to extremist militancy, but most are likely to assent to the religious ideology that provides the identity of the people.

One of the themes that appears repeatedly in the work of Sam Harris is that religious moderates provide cover for religious extremists, so while religious moderates don’t commit ghastly crimes in the name of religion, they implicitly facilitate ghastly crimes committed in the name of religion. Here is the passage in The End of Faith where Harris introduces this theme:

“…people of faith fall on a continuum: some draw solace and inspiration from a specific spiritual tradition, and yet remain fully committed to tolerance and diversity, while others would burn the earth to cinders if it would put an end to heresy. There are, in other words, religious moderates and religious extremists, and their various passions and projects should not be confused. One of the central themes of this book, however, is that religious moderates are themselves the bearers of a terrible dogma: they imagine that the path to peace will be paved once each of us has learned to respect the unjustified beliefs of others. I hope to show that the very ideal of religious tolerance — born of the notion that every human being should be free to believe whatever he wants about God — is one of the principal forces driving us toward the abyss.”

Sam Harris, The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason, New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2005

For Harris, religious moderation is not a welcome respite from fanaticism, but a pretext for reasonable people who are vague about their religious beliefs to make excuses for unreasonable people who are clear and unambiguous about their religious beliefs. Ideological moderation provides cover for ideological extremism, and ideological extremism provides cover for militancy. I haven’t read anything In Harris’ work in which he identifies this as a principle, but it is a principle, and, like many principles conceived to explain some particular aspect of the world, it can be generalized as a explanation across many other aspects of the world.

Thus in the same spirit of Harris’ principle that religious moderates provide cover for religious extremists, we can generalize this principle such that ideological moderates of any kind, subscribing to any set of (vaguely held) beliefs, provide cover for ideological extremists who are willing to put their beliefs into practice in an uncompromising form. I will call this the principle of facilitating moderation, since, according to the principle, moderates facilitate the beliefs and actions of extremists. This, as we shall see, is the great stumbling block in winning hearts and minds.

The generalization of Harris’ principle from religion to any ideology whatsoever makes it easier to understand extremist ideologies like communism and fascism (or even simple nationalism) in terms of the same principle without having to argue that such non-religious ideologies are surrogate religions. (I do not disagree with this argument; I have, in fact, made this argument in Mythologies of Industrialized Civilization, but I also know that many people reject the idea of religious surrogates, and as this is not necessary to the argument in the present case, I need not make that argument here in order to make my point.)

Another theme that appears repeatedly in Sam Harris’ lectures is that different religions are adaptable to a greater or lesser extent to being transformed into a suicide cult; some religions are very easily exapted to this end, while others are not at all easily exapted to this end. (Harris makes this point repeatedly in his lectures, but I did not find this explicit argument in his books.) In other words, not all religions are alike in the danger than they pose as pretexts for violent militancy, and Harris goes on to explicitly single out Islam as especially vulnerable to being exapted for violent militancy.

It is a moral “softball” to discuss Islamic suicide terrorism, as this is a topic on which almost all Westerners are in a agreement. It is more morally problematic — and therefore perhaps will better challenge us to sharpen our formulations — if we consider the relative peaceableness of Buddhists and their institutional representatives — a group which Harris explicitly singles out as much less likely to engage in religiously-motivated militancy than Muslims. The way to make intellectual progress is to take a problem at its hardest point and to seek the solution there, avoiding easy answers that cannot hold up in extreme circumstances. (Does this make me an intellectual extremist? Perhaps so.)

Harris contends that it would be much more difficult to transform Buddhism into a suicide cult than Islam, and I want to explicitly say that I do not disagree with this, but… one of the most powerful moments in the Viet Nam war that demonstrated that the US was not only not winning hearts and minds, but was rather disastrously losing them by its support of the Ngô Đình Diệm government, was when Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức burned himself to death in Saigon in 1963 to protest the treatment of Buddhists by the government of Ngô Đình Diệm. While the self-immolation of Thích Quảng Đức harmed no one but himself, it would be difficult to imagine a more “inflammatory” symbol of political protest (and please forgive me for that unfortunate formulation).

It would be difficult to identify self-immolation as anything other than an act of extremism, and it is ideological extremism that motivates ideological militancy. Buddhist monks who protest by self-immolation (and there have been many) represent an extreme form of violence, though as violence turned against oneself it causes no direct harm to others. In practical politics, however, spectacular violence toward oneself — a category that includes suicide bombings — may have the same effect as spectacular violence toward others. Buddhist monks who have spent a lifetime in meditation on the human condition should know well the reaction of the ordinary person to such a spectacle, and it is not likely to be peaceful.

The act of violence in the context of a mostly non-violent community, which latter seeks only to retain its identity and to go about with the ordinary business of life, presents a fundamental problem for counter-insurgency. In any effort to win hearts and minds it is essential to distinguish between those who assent to a given ideology, no matter how extreme, but who make no effort to engage in an armed struggle (or to aid and support such an armed struggle) and those who do engage in militancy, acting upon calls for violent intervention. Terrorism follows from militancy, and militancy follows from extremism, but if strong ideological views are tarred with the same brush as militancy there is the danger of pushing peaceful ideologues over the threshold of militancy and joining in armed struggle.

Most people, no matter how strongly they believe in a given ideology, do not engage in militant action but are willing to work within the established framework of society to attain their ends. Such individuals, and the groups that represent them and speak on their behalf, must not be alienated in any counter-insurgency campaign. On the contrary, they must be cultivated. It is this moderate majority whose hearts and minds must be won if peace is to be established and militants marginalized.

However, it is also this moderate majority that, according to the principle of facilitating moderation, make it possible for extremist ideology and militant groups motivated by extremist ideology to persist. And if the moderate majority are alienated, they are likely, at the very minimum, to give their support to violent militants. Chairman Mao, who came to power through guerrilla warfare and knew a thing or two about it, famously said that, “The guerrilla must move amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea.” In other words, Mao clearly understood the principle of facilitating moderation, given that the guerrilla is the militant who moves among moderates who support and sustain him. Some alienated moderates may also pass beyond disaffection and support of violent militants and may become active militants themselves.

The inherent tension in the relationship between the non-violent majority and the violent minority who turn to militancy is held in check by a shared vision of the world, the common ideology of militant and non-militant, and this means that while individuals may disagree on ways and means, they are likely to agree on the end in view. I wrote about this previously, coming from a slightly different angle, in Cosmic War: An Eschatological Conception:

Because a cosmic war does not occur in a cosmic vacuum, but it occurs in an overall conception of the world, the grievances too occur within this overall conception of history. If we attempt to ameliorate grievances formulated in an eschatological context with utilitarian and pragmatic means, no matter what we do it will never be enough, and never be right. An eschatological solution is wanted for grievances understood eschatologically, and that is why, in at least some cases, religious militants turn to the idea of cosmic war. Only a cosmic war can truly address cosmic grievances.

Sam Harris makes a similar point:

“In our dialogue with the Muslim world, we are confronted by people who hold beliefs for which there is no rational justification and which therefore cannot even be discussed, and yet these are the very beliefs that underlie many of the demands they are likely to make upon us.”

Sam Harris, The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason, New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2005

This fundamental tension between winning hearts and minds and successfully combating violent extremists whose hearts and minds overlap to a significant degree with the non-violent majority cannot be wished away; there will always be a trade-off between placing more emphasis on fighting an insurgency or winning hearts and minds. The generality of this result is suggested by the fact that I first formulated this idea in Anti-Technology Terrorism: An Upcoming Global Threat?, and the generality of this result suggests to danger to which we are exposed.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Tuesday

As Syria continues its slide from insurgency into civil war, and no one any longer expects the ruling Alawite regime of Bashar al-Assad to triumph, it is an appropriate moment in history to reflect upon the fall of tyrants and tyrannical regimes. Not that we haven’t had ample opportunity to do so in recent years. The fall of the Soviet Union in the late twentieth century and the fall of a series of Arab dictators in recent years has given us all much material for reflection (chronicled in posts such as Cognitive Dissonance Among the Apologists for Tyranny and Two Thoughts on Libya Nearing Liberation).

I have previously written about Syria in Things fall apart, Open Letter in the FT on Syria, The Structures of Autocratic Rule, and What will Assad do when he goes to Ground? Much more remains to be said, on Syria in particular and on the collapse of tyrants generally.

The obvious problems of governmental succession in Syria are already being discussed ad nauseam in the press. That there is trouble on the horizon is evident to all who carefully follow the developments of the region in which Syria is a central nation-state, bordering no fewer than five nation-states: Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south and Israel to the southwest. This centrality of Syria in a politically unstable region has led the surrounding regional powers to favor the devil they know rather than to chance the devil they know not. The ruling Alawite regime of Syria has been held in place not only by its own brutality, but also by the tacit consent of its neighbors. Now that the fall of the al-Assad dynasty is in sight, there are legitimate worries about the radicalization of the insurgents and the role of Islamist Jihadis in the insurgency. No one knows what will come out of this toxic stew, but it is likely to resemble a failed state even upon its inception.

At this moment in history, Syria is now the bellweather for the fall of tyrants, but Syria is only the current symptom of an ancient problem that goes back to the dawn of state power in human history. Since the earliest emergence of absolute state power in agricultural civilization, for the first time in human history sufficiently wealthy to support a standing army that could be employed by turns to oppress a tyrant’s own people or as an instrument to conquer and oppress other peoples, there has been a tension between the ability of absolute power to effectively exercise this absolute power to maintain itself in power and the ability of rivals or of subject peoples to wrest this power from the hands of absolute rulers and seize it for themselves.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see that the institutions of tyrannical political rule are not sustainable. Tyrannical rule may be sustainable for the life of a tyrant, or for a few generations of a dynasty established by a tyrant, but history teaches us that tyrannical longevity is the exception and not the rule. The more onerous the rule of the tyrant, the more other factions will risk to overthrow the tyrant. A tyrant who sufficiently modifies his tyranny until it is approximately representative is likely to last much longer in power, and over time approximates non-tyrannical rule. But if a tyrant simply cuts a few others in on the spoils, creating a tyrannical oligarchy, the same considerations apply. In the long term, only popular rule is sustainable.

But what does this mean to say that in the long term only popular rule is sustainable? The learned reader at this point in likely to begin a recitation of the failings of democracy, but I didn’t say that only democratic regimes persist. Unfortunately for most human beings throughout history, the fall of a tyrant has not resulted in democracy. The most vicious tyrannies call forth the most vicious elements in the population as the only agents willing to risk the overthrow of the tyrant, and so one tyrant is likely to be replaced by another. Even if a popular revolt and revulsion helped to topple the previous tyranny, the new tyranny reverts to perennial tyrannical form, and in so doing eventually alienates the popular movement that installed it in place of the previous tyranny.

This is a particular case of what I have called The Failure Cycle, since this pattern can be iterated. Much of human history has consisted of just such an iteration of petty tyrants, one following the other. That nothing is accomplished politically by the churning of tyrannical regimes should be obvious. There is no social evolution, no social growth, no strengthening of institutions that can provide continuity beyond the vagaries of personal rule.

Thus one consequence of the fact that only popular rule is sustainable is the possibility of an endless iteration of popular movements to overthrow serial tyranny, each tyrant in turn having been installed by a popular uprising. This constitutes a perverse kind of “popular” rule, though it is not often recognized as such or called as much.

Tyrannical regimes typically bend every effort in order to suppress, or at very least to delay, social change. The suppression and delay of social change means that societies laboring under tyrannical regimes — and especially those that have labored under a sequence of tyrannical regimes — have little opportunity to allow social change to come to maturity and for old institutions to be allowed to die while new institutions rise to take their place. Cynics will opine that there is no social evolution in human history, but I deny this. Social evolution is possible, if rare, but the conditions that lead to serial tyranny and serial popular uprisings are not conducive to the cultivation of social evolution.

It is the historical exception to interrupt this vicious cycle of serial tyranny and serial popular uprising, but it takes time for informal social institutions to reach the level of maturity that allows a popular uprising to install a genuine democracy instead of a tyrant who claims to be a democrat out of political expediency.

Homo non facit saltus. Man makes no leaps. We cannot skip a stage in our social evolution. We cannot impose democratic institutions, or freedom, or even prosperity. A people must come to it on their own, with the maturation of their native institutions, or not at all.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .