The Moral Value of Defiance

29 May 2016

Sunday

The Defiance of Nadiya Savchenko

I don’t believe that I have ever seen a more complete or perfect expression of defiance than that on the face of Nadiya Savchenko, a Ukrainian pilot who was until quite recently imprisoned in Russia (and who was elected to the Ukrainian parliament during her imprisonment). This display of defiance is an appropriate opportunity to consider the nature of defiance as an emotion (specifically, a moral emotion) and its place within human life.

It is a natural human response to feel angry when confronted with obvious injustice. When that injustice is not merely observed, but involves ourselves personally, there is also a personal element to the anger. When an individual is angry for an injustice done to themselves, and is not yet defeated, but possesses the strength and the energy to persevere despite on ongoing injustice, that is defiance.

I am sure everyone reading this has had this experience to some degree; this is a universal that characterizes the human condition. This kind of defiance is a staple of classic literature; for example, we know defiance as the spirit of the protagonist of Jane Eyre:

“When we are struck at without a reason, we should strike back again very hard; I am sure we should — so hard as to teach the person who struck us never to do it again… I must dislike those who, whatever I do to please them, persist in disliking me; I must resist those who punish me unjustly. It is as natural as that I should love those who show me affection, or submit to punishment when I feel it is deserved.”

The young friend of Jane Eyre, Helen Burns, replies:

“Heathens and savage tribes hold that doctrine, but Christians and civilised nations disown it.”

When published Jane Eyre was considered something of a scandal, and Matthew Arnold (of “Sweetness and Light” fame) said of the novel, “…the writer’s mind contains nothing but hunger, rebellion and rage and therefore that is all she can, in fact, put in her book.” Another Victorian critic wrote, “…the tone of mind and thought which has overthrown authority and violated every code human and divine abroad, and fostered Chartism and rebellion at home, is the same which has also written Jane Eyre.” (Elizabeth Rigby, The London Quarterly Review, No. CLXVII, December, 1848, pp. 82-99) Today we recognize ourselves in the protagonist without hesitation, for what comes naturally to the unbroken spirit of Jane Eyre comes naturally to all of us; it resonates with the human condition (except, perhaps, for the condition of Victorian literary critics). There is much more that could be said in regard to Victorian attitudes to defiance, especially among children, but I will save this for an addendum.

Defiance as a Moral Emotion

Our conventional idea of an emotion as something that we passively experience — emotions were traditionally called passions because they are affects that we suffer, and not actions that we take — is utterly inadequate to account for an emotion like defiance, which is as much action as passion. At least part of the active nature of defiance is its integration with our moral life, which latter is about active engagements with the world. For this reason I would call defiance a moral emotion, and I will develop the idea of moral emotion in the context of emotive naturalism (see below).

Moral emotions are complex, and it scarcely does them justice to call them emotions. The spectrum of emotion ranges from primarily visceral feelings with little or no cognitive content, and indistinguishable from bodily states, to subtle states of mind with little or no visceral feelings associated with them. Some of our emotions are simple and remain simple, but many states of human consciousness that we carelessly write off as emotions are in fact extremely sophisticated human responses that involve the entire person. Robert C. Solomon’s lectures Passions: Philosophy and the Intelligence of Emotions do an excellent job of drawing out the complexities of how our emotional responses are tied up in a range of purely intellectual concerns on the one hand, and on the other hand almost purely visceral feelings.

Solomon discusses anger, fear, love, compassion, pride, shame, envy, jealousy, resentment, and grief, though he does not explicitly take up defiance. In several posts I have discussed fear (The Philosophy of Fear and Fear of Death), hope (The Structure of Hope and Very Short Treatise on Hope, Perfection, Utopia, and Progress), pride (Metaphysical Pride), modesty (Metaphysical Modesty), and ressentiment (Freedom and Ressentiment), though it could in no sense be said that I have done justice to any of these. The more complex moral emotions are all the more difficult to do justice to; specifically moral emotions such as defiance present a special problem for theoretical analysis.

The positivists of the early twentieth century propounded a moral theory that is known as the emotive theory of ethics, which explicitly sought a reduction of morality to emotion. This kind of reductionism is not as popular with philosophers today, and for good reason. While we would not want to reduce morality to emotion (as the positivists argued), nor to reduce emotions to corporeal sensations (a position sometimes identified with William James), in order to make sense of our emotional and moral lives it may be instructive to briefly consider the origins of emotion and morality in the natural history of human beings. This natural historical approach will help us to account for the relevant evidence without insisting upon reductionism.

Emotive Naturalism

What emotions are natural for a human being to feel? What thoughts are natural for a human being to think? What moral obligations is it natural for a person to recognize? All of these are questions that we can reasonably ask about human beings, since we know that human beings feel, think, and behave in accordance with acknowledged obligations. I wrote above that it is natural for one to feel anger over injustice. If you, dear reader, have never experienced this, I would be surprised. No doubt there are individuals who do not, and who never have, experienced anger as a result of injustice, but this is not the typical human response. But the typical “human” response is descended with modification from the typical responses of our ancestors, extending into the past long before modern human beings evolved.

I have elsewhere quoted Darwin on the origins of morality, and I think the idea contained in the following passage cannot be too strongly emphasized:

“The following proposition seems to me in a high degree probable — namely, that any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts… the parental and filial affections being here included, would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience, as soon as its intellectual powers had become as well, or nearly as well developed, as in man.”

Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, CHAPTER III, “COMPARISON OF THE MENTAL POWERS OF MAN AND THE LOWER ANIMALS”

I would go further than Darwin. I would say that animals with intellectual powers less developed than those of humanity might acquire a moral sense, and that we see such a rudimentary moral sense in most social animals, which are forced by the circumstances of lives lived collectively to adopt some kind of pattern of behavior that makes it possible for group cohesion to continue.

There are many species of social animals that live in large groups that necessitate rules of social interaction. Indeed, we even know from paleontological evidence that some species of flying dinosaurs lived in crowded rookeries (there is fossil evidence for this at Loma del Pterodaustro in Argentina), so that we can derive the necessity of some form of social interaction among residents of the rookery. Many of these social animals have very little in the way of intellectual powers, such as in the case of social insects, but there are also many mammal species, all part of the same adaptive radiation of mammals that followed the extinction of the dinosaurs and of which we are a part, and constituting the sentience-rich biosphere that we have today. Social mammals add to the necessity of social rules for group interactions an overlay of emotive responses. Already in groups of social mammals, then, we begin to see a complex context of social interaction and emotional responses that cannot be isolated one from the other. With the emergence human intellectual capacity, another overlay makes this complex context of social interaction more tightly integrated and more subtle than in prior social species.

I call these deep evolutionary origins of human emotional responses to the world emotive naturalism, but I could just as well call it moral naturalism — or indeed, intellectual naturalism, because by the time human beings emerge in history emotions, morality, and cognition are all bound up in each other, and to isolate any one of these would be to falsify human experience.

Being and Emotion

While the philosophy of emotion is usually discussed in terms of philosophy of mind or philosophical psychology, I usually view philosophical problems through the lens of metaphysics, and the active nature of defiance as a moral emotion gives us an especially interesting case for examining the nature of our emotional and moral being-in-the-world. This accords well with what Robert Solomon argued in the lectures cited above, which characterize emotions as engagements with the world. What is it to be engaged with the world?

My framework for thinking about metaphysics is a definition of being that goes back all the way to Plato, which I discussed in Extrapolating Plato’s Definition of Being (and which I further elaborated in Agents and Sufferants). Plato held that being is the power to affect or to be affected, i.e., to act or to be acted upon. From this starting point we can extrapolate four forms be being, such that non-being is to neither act nor be acted upon, the fullness of being is to both act and be acted upon, while narrower forms of being involve acting only without being acted upon, or being acted upon only without acting. One may think of these four permutations of Plato’s definition of being as four modalities of engagement with the world.

An interesting example of metaphysical engagement with the world in terms of a moral emotion radically distinct from defiance is to be found with our engagements with the world mediated by love. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux in Sermon 50 of his Sermons on the Song of Songs wrote, “Love can be a matter of doing or of feeling.” In other words, love can be active or passive, acting or being acted upon. St. Bernard goes on to give several illuminating examples that develop this theme.

How does the moral emotion of defiance specifically fit into this framework of engagements with the world? We typically employ the term “defiance” when an individual’s circumstances severely constrain their ability to respond, as was the case with Nadiya Savchenko, who was incarcerated and who therefore was prevented from the ordinary freedom of action enjoyed by those of us who are not incarcerated. Nevertheless, she was able to remain defiant even while in prison, and under such circumstances the emotion itself becomes a response. (The reader who is familiar with Sartre’s thought will immediately recognize the connection with Sartre’s theory of emotion; cf. The Emotions: Outline of a Theory) This may sound like a paltry form of “action,” but if it contributes to the differential survival of the individual, defiance has a selective advantage, as it almost certainly must. Defiant individuals have not given up, and they continue to fight despite constrained circumstances.

The Social Context of Defiance

The survival value of belief in one’s existential choices, which I discussed in Confirmation Bias and Evolutionary Psychology, is exemplified by defiance. Defiance, then, has the ultimate evolutionary sanction: it is a form of confirmation bias — belief in oneself, and in one’s own efficacy — that contributes to the individual’s differential survival. As such, defiance as a moral emotion is selected for and is likely disproportionately represented in human nature because of the selective advantage it possesses. As a feature of human nature, we must reckon with defiance as a socially significant emotion, i.e., an emotion that shapes not only individuals, but also societies.

While we do not often explicitly talk about the role of defiance in human motivation, I believe it is one of the primary springs to action in the human character. Looking back over a lifetime of conversations occurring in the ordinary business of life (for I am an old man now and I can speak in this idiom), I am struck by how often individuals express their displeasure at pressures being brought to bear upon them, and they usually respond by pushing back. This “pushing back” is defiance. Typically, the other side then pushes back in turn. This is the origin of tit-for-tat strategies. Individuals push back when pressured, as do social wholes and political entities. Those that push back most successfully, i.e., the most defiant among them, are those that are most likely to have descendants and to pass their defiance on to the next generation of individuals or social wholes.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Teleological and Deontological Conceptions of Civilization

7 September 2014

Sunday

Teleology and Deontology

In moral theory we distinguish between teleological ethical systems and deontological ethical systems. Teleological ethics (also called consequentialism, in reference to consequences) focus on the end of an action, i.e., that actual result, as that which makes an action praiseworthy or blameworthy. The word “teleological” comes from the Greek telos (τέλος), which means end, goal, or purpose. Deontological ethics focus on the motivation for undertaking an action, and is sometimes referred to as “duty-based” ethics; the word “deontological” derives from the Greek deon (δέον), meaning “duty.”

The philosophical literature on teleology and deontology is vast. From this vast literature the history of moral philosophy gives us several well known examples of both teleological and deontological ethics. Utilitarianism is often cited as a paradigmatic example of teleological ethics, as utilitarianism (in one of its many forms) holds that an action is to be judged by its ability to bring about the greatest happiness for the greatest number of persons (also known as the greatest happiness principle). Kantian ethics is usually cited as the paradigmatic case of deontological ethics; Kant placed great emphasis upon duty, and held that nothing is good in itself except the good will. These philosophical expressions of the ideas of teleology and deontology also have vernacular expressions that largely coincide with them, as, for example, when teleological views are expressed as, “the ends justify the means,” or when deontological views are expressed as “justice be done though the heavens may fall.”

The vast literature on deontology and teleological also points to many examples that show these categories of ethical thought to be overly schematic and, in some cases, to cut across each other. For example, if we characterize teleological ethics in terms of the aim to be achieved by an action, a distinction can be made between the actual consequences of an action and the intended consequences of an action. The intended consequences of an action may be understood deontologically as the motivation for undertaking an action. Part of this problem can be addressed by tightening up the terminology and the logic of the argument, but, as has been noted, the literature is vast and many sophisticated arguments have been advanced to demonstrate the interpenetration of teleological and deontological conceptions. We must, then, regard this distinction as a rough-and-ready classification that admits of exceptions.

Teleology and Deontology in a Social Context

We can take these ideas of teleological and deontological ethics and apply them not only to individual action but to social action, and thus speak of the actions of social groups of human beings in teleological or deontological terms, i.e., we can speak in terms of the coordinated actions of a group being undertaken primarily in order to achieve some end, or actions undertaken as ends-in-themselves. This suggests the extrapolation of teleological and deontological conceptions to the largest social formations, and the largest social formation known to us is civilization. Can a civilizaiton entire be teleological or deontological in its outlook? Does a civilization have a moral outlook?

I will assume, without arguing in detail, that a civilization can have a moral outlook, understanding that this is a generalization that holds across a civilization, and that the generalization admits of numerous important exceptions. Elsewhere I have noted the Darwinian perspective that any social group of animals that lives together in sufficient density for a sufficient period of time will evolve social customs for interaction. (This is a position that has been further explored in our time by Frans de Waal and Soshichi Uchii.) The lifeway of a particular people is coextensive with social conventions necessary for a social species to live together in a reasonable degree of harmony; what distinguishes regional permutations of lifeways are the climate and available domesticates. Both ethics and civilization grow from this common root, hence the xenophobia of traditionalist civilizations that unproblematically equate the peculiarities of a particular regional civilization with the good in and of itself.

Can this synthesis of lifeways and ethos that marks out a regional civilization (and which is consolidated in the process of axialization) be characterized as overall teleological or deontological orientation in some particular cases? This is a more difficult question, and rather than tackling it directly, I will discuss the question from various perspectives drawn from an overview of the history of civilization.

Teleology and Deontology in Agrarian-Ecclesiastical Civilization

The emergence of settled agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization presents us with an archaeological horizon that appears globally in widely dispersed locations but at approximately the same time. (An archaeological horizon is “a widely disseminated level of common art and artifacts.” Wikipedia) Prior to an actual horizon, there are a great many suggestive sites that imply both domestication and semi-settled lifeways, but at a certain level (between 9 and 11 thousand years before present) the traces of large scale settlement and domestication of plants and animals becomes common. This is the horizon of civilization (or, more narrowly, the horizon of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization).

The horizon of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization exhibits global characteristics that eventually culminate in the Axial Age, when regional civilizations are given definitive expression in mythological terms. Through separately emergent, these civilizations exhibit common features of settlement, division of labor, social hierarchy, a conception of the world, of human nature, and of the relation between the two that are expressed in mythological form, which in being made systematic (an early manifestation of the human condition made rigorous) become the central organizing idea of the civilizations that followed. This period represents the bulk of human civilization history to date, a period lasting almost ten thousand years.

Recently on my other blog I undertook a series on religious experiences and religious observances from hunter-gatherer nomadism through contemporary industrial-technological civilization and on into the future — cf. Settled and Nomadic Religious Experience, Religious Experience in Industrial-Technological Civilization, Religious Experience and the Future of Civilization, Addendum on Religious Experience and the Future of Civilization, and Responding to the World we Find — and thinking of religious observances emergent from human religious experience it is difficult to say whether these ritual observances are performed in the spirit of teleology or deontology, i.e., whether it is the consequences of the ritual that matters, or if the ritual has intrinsic value and ought to be conducted regardless of consequences. This may be one of the many cases in which teleological and deontological categories cut across each other. Agrarian-eccleasiastical civilization at times seems to formulate its central organizing principle of religious observance in terms of the intrinsic value of the observance, and in times in terms of the efficacious consequences of these observances.

We can understand religion (by which I mean the central organizing principle of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilizations) as an existential risk mitigation strategy for pre-technological peoples, who have no method to address personal mortality or the cyclical rise and fall of civilizations (i.e., civilizational mortality) other than the propitiation of gods; once the transition is made from agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization to industrial-technological civilization, the methods of procedural rationality that are the organizing principle of the latter can be brought to bear on existential questions, and it finally becomes possible for existential threats to be assessed and addressed on the level of naturalistic human action. It would not have been possible to conceptualize existential risk in terms of naturalistic human action prior to the technological expansion of effective human action.

Teleology and Deontology in Global Industrial-Technological Civilization

Civilization is an historical reality that exhibits change and development over time. The particular change in civilization that we see at the present time is a transition from regional civilizations, reflecting the coevolution of human beings and domesticates (both plant and animal) ecologically suited to a particular geographical region, to a global industrial-technological civilization that is largely indifferent to local and regional ecological and climatological conditions, because a global trade network provides goods and services from any region to any other region, which means that the maintenance of civilization is no longer dependent upon local or regional constraints.

This development of global industrial-technological civilization is likely to dominate civilization until civilization either fails (i.e., civilization experiences extinction, permanent stagnation, flawed realization, or subsequent ruination) or expands beyond Earth and a self-sustaining center of civilization emerges in space or on another planetary body. In order for the latter to occur, human travel in space must move beyond exploratory forays and become commonplace, that is to say, we would have to see a horizon of space travel. I have called the horizon of human space travel extraterrestrialization. Until that time, civilization remains bound by the finite surface of Earth, and this means that our civilization is growing intensively rather than extensively. The intensive growth of regional civilizations exhaustively covering the surface of Earth means the closer integration of these civilizations (sometimes called globalization), and it is this process that is pushing regional civilizations (e.g., Chinese civilization, Indian civilization, European civilization, etc.) toward integration into a single global industrial-technological civilization.

The spatial constraint of the Earth’s surface together with the expansion and consolidation of settled industrial-technological civilization forces these civilizations into integration, even if only at the margins where their borders meet. Is this de facto constraint upon planetary civilization a mere contingency pushing civilization in a particular direction (which in evolutionary terms could be called civilizational directional selection), or may be think of these constraints in non-contingent terms as a “destiny” of planetary civilization? We find both conceptions represented in contemporary thought.

To think of civilization in terms of destiny is to think in teleological terms. If civilization has a destiny apart from the purposes of individuals and societies, that destiny is the telos of that civilization. But we would not likely refer to an historical accident that selects civilization as “destiny,” even if it shapes our civilization decisively. If we reject the idea of a contingent destiny forced upon us by de facto constraints upon growth and development, then we are implicitly thinking of civilization in terms of practices pursued for their own ends, which is an deontological conception of civilization.

The contemporary idea of a transition to a sustainable civilization — the transition from an industrial infrastructure powered by fossil fuels to an industrial infrastructure based on sustainable and renewable sources of fuel — is clearly a deontological conception of the development of civilization, i.e., that such a transition needs to take place for its own sake, but this deontological ideal of a civilization that lives within its means also implies for many who hold this idea a vision of future civilization that has been revamped to avoid the morally catastrophic mistakes of the past, and in this sense the conception is clearly teleological.

The Historico-Temporal Structure of Human Life

One of the most distinctive features of human consciousness is its time consciousness that extends into an explicit understanding of the future and its relationship to present action, and which developed and iterated becomes historical consciousness, in which the individual and the social group understands himself or itself to stand in relation to a past that preceded the present, and a future that will follow from the present. This historico-temporal structure of human life, both individual and communal, means that human beings plan ahead and make provision for the future in a much more systematic way than any other terrestrial species. This consideration alone suggests that the primary ethical category for understanding human action must be teleological. But this presents us with certain problems.

Civilization itself, and the great processes of civilization such as the Neolithic Agricultural Revolution, urbanization, and industrialization, were unplanned developments that just happened. No one planned to build a civilization, and no one planned for regional civilizations to run into planetary constraints and thus to begin to integrate into a global civilization. So although human beings have the ability to plan and the carry out long term projects, many of the historical human realities that are among the most significant in shaping our lives both individually and collectively were not planned. In the future we may be able to plan a civilization or civilizational process and bring this plan to a successful conclusion, but nothing like this has yet been accomplished in the history of civilization. The closest we have come to this is to build planned communities or cities, and this falls far short of the construction of an entire civilization. Until we can do more, we are subject to a limited teleological civilizational ethos at most.

Teleological and Deontological Sources of Civilization

While agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization tends to organize around an eschtological destiny, and is therefore profoundly teleological in outlook, and industrial-technological civilization tends to organize around procedural rationality, and is therefore profoundly deontological in outlook, we can think of a prehistoric past that is the source of both of these paradigms of civilization as either essentially teleological or deontological.

The basic historico-temporal properties of human life noted above, iterated, extended, and eventually made systematic culminate in an organized and communal way of life for a social species, and this telos of human activity is civilization. Civilization on this view is inherent in human nature. This can be expressed in non-naturalistic, eschatological terms, and this probably the form in which this conception is most familiar to us, but it can also be expressed in scientific terms. Here is Carl Sagan’s expression of this idea:

The cerebral cortex, where matter is transformed into consciousness, is the point of embarkation for all our cosmic voyages. Comprising more than two-thirds of the brain mass, it is the realm of both intuition and critical analysis. It is here that we have ideas and inspirations, here that we read and write, here that we do mathematics and compose music. The cortex regulates our conscious lives. It is the distinction of our species, the seat of our humanity. Civilization is a product of the cerebral cortex.

Carl Sagan, Cosmos, Chapter XI, “The Persistence of Memory”

In my post 2014 IBHA Conference Day 2 I mentioned the presentation of William Katerberg, in which he characterized ideas of inevitability and impossibility as forms of teleology in scientific historiography. While Sagan may not be asserting the inevitability of civilization emerging from the cerebral cortex, all of these conceptions belong under the overarching umbrella of teleology, whether weakly teleological or strongly teleological.

When we consider the highest expressions of the human mind in intellectual and aesthetic production, it is not at all clear if these monuments of human thought are undertaken for their intrinsic value as ends in themselves, or if they have been pursued with an eye to some end beyond the construction of the monument. Consider the pyramids: are these monuments to glorify the Pharaoh, and thus by extension to glorify Egyptian civilization as an end in itself, or are these monuments to secure the eternal reign of the Pharaoh in the afterlife? Many of the mysterious monuments that remain from past civilizations — Stonehenge, Carnac, Göbekli Tepe, the Moai of Easter Island, and the Sphinx, inter alia — have this ambiguous character.

We can imagine a civilization of the prehistorical past essentially called into being by the great effort to create one of these monoliths. The site of Göbekli Tepe is one of the more recent and interesting discoveries from the Neolithic, and some archaeologists that suggested that the site points to civilization coming into being for the purpose of constructing and maintaining this ritual site (something I mentioned in The Birth of Agriculture from the Spirit of Religion).

Teleology, Deontology, and a Philosophy of History

Teleology has been subject to much abuse in the history of human thought, as I have noted on many occasions. There is a strong desire to believe in meaning and purpose that transcends the individual, if not the entire species. The essentially incoherent desire for an meaning or purpose coming from outside the world entire, entering into the world from outside and giving a purpose to mundane actions that these actions cannot derive from any source within the world, is an imperfectly expressed theme of almost all religious thought. Logically, this is the desire for a constructive foundation for meaning and purpose; finding meaning or purpose for the world from within the world is an inherently non-constructive conception that leaves a vaguely dissatisfied feeling rarely brought to logical clarification.

The first great work in western philosophy of history, Saint Augustine’s City of God, is a thoroughly teleological conception of history culminating in the -. Perhaps the next most influential philosophy of history after Augustine was that of Hegel, and, again, Hegel’s philosophy of history is pervasively teleological in spirit. A particular philosophical effort is required to conceive of human history (and human civilization) in non-Augustinian, non-Hegelian terms.

Does there even exist, in the Western philosophical tradition, a deontological philosophy of civilization? In light of the discussion above, I have to examine my own efforts in the philosophy of history, as I realize now that some of my formulations could be interpreted as implying that civilization is the telos of human history. Does human history culminate in human civilization? Is civilization the destiny of humanity? If so, this should be made explicit. If not, a more careful formulation of the relationship of civilization to human history is in order.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Developmental Axiology: Intrinsic Value over Time

26 June 2014

Thursday

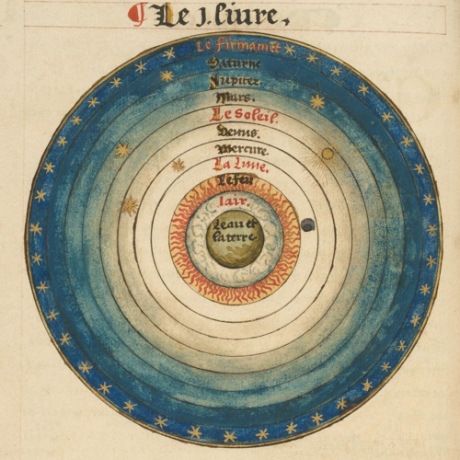

Once upon a time it was believed that the world was eternal and unchanging. The inconvenient truth of life and death of Earth was accommodated by a distinction between the sublunary and the superlunary: in Ptolemaic astronomy, the “sublunary” was everything in the cosmos below the sphere of the moon, and this was subject to time and change and suffering; the superlunary was everything in the cosmos beyond the sphere of the moon, which was eternal, perfect, unchanging, and permanent. Thus it was a major problem when Galileo turned his telescope on the moon and saw craters, and when he looked at the sun he saw spots. This wasn’t supposed to happen.

As a result of Galileo and the scientific revolution, we are still re-thinking the world, and each time we think that we have the world caught in a net of concepts, it escapes once again. Up until 1999 it was widely believed that the universe was expanding at a decreasing rate, and the only question was whether there was enough mass for this expansion to eventually grind to a halt, and then perhaps the universe would contract again, or if the universe would just keep coasting along in its expansion. Now it seems that the expansion of the universe is speeding up, and it is widely thought that, in a very early stage of the universe’s existence, it underwent an extremely rapid phase of expansion (called inflation).

When the scientific revolution at long last came to biology, Darwin and evolution and natural selection exploded in the scientific imagination, and suddenly a human history that had seemed neat and compact and easily circumscribed became very old, large, and messy. We recognize today that all life on the planet evolved, and that in the short interval of human life, the human mind has evolved, language has evolved, social institutions have evolved, civilization has evolved, and technology has evolved perhaps more rapidly than anything else.

The evolution of human social institutions has meant the evolution of human meanings, values, and purposes: precisely those aspects of human life that were once invested with permanency and unchangeableness in an earlier paradigm of human knowledge. Human knowledge evolves also. Science as the systematic pursuit of knowledge (since the scientific revolution, and especially since the advent of industrial-technological civilization, which is driven forward by science) has pushed the evolution of human knowledge beyond all precedent and expectation. As I recently noted in The Moral Truth of Science, science is a method and not a body and knowledge, and even the method itself changes as it is refined over time and adapted to different fields of study.

Slowly, painfully slowly, we are becoming accustomed to an evolving world in which all things are subject to change. The process does not necessarily get easier, though one might easily suppose we get numbed by change. In fact, when all our previous assumptions are forced to huddle down in a single relict of archaic thought, it can be extraordinarily difficult to get past this last stubborn knot of human thought that has attached itself passionately to the past.

I think that it will be like this with our moral ideas, which are likely to be sheltered for some time to come, and in so far as they are sheltered, they will conceal more prejudices that we would like to admit. Even those among us who are considered progressive, if not radical, can take a position that essentially protects our moral prejudices of the past. John Stuart Mill was among the most reasonable of men, and it is difficult to disagree with his claims. While in his day utilitarianism was considered radical by some, now Mill is understood to be an early proponent of the political liberalism that is taken for granted today. But the quasi-logical form that Mill gave to his ultimate moral assumptions is entirely consistent with the fideism of radical Ockhamists or Kierkegaard.

Here is a classic passage from a classic work by Mill:

Questions of ultimate ends are not amenable to direct proof. Whatever can be proved to be good, must be so by being shown to be a means to something admitted to be good without proof. The medical art is proved to be good by its conducing to health; but how is it possible to prove that health is good? The art of music is good, for the reason, among others, that it produces pleasure; but what proof is it possible to give that pleasure is good? If, then, it is asserted that there is a comprehensive formula, including all things which are in themselves good, and that whatever else is good, is not so as an end, but as a mean, the formula may be accepted or rejected, but is not a subject of what is commonly understood by proof. We are not, however, to infer that its acceptance or rejection must depend on blind impulse, or arbitrary choice. There is a larger meaning of the word proof, in which this question is as amenable to it as any other of the disputed questions of philosophy. The subject is within the cognisance of the rational faculty; and neither does that faculty deal with it solely in the way of intuition. Considerations may be presented capable of determining the intellect either to give or withhold its assent to the doctrine; and this is equivalent to proof.

John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism, Chapter 1

Formulating his moral thought in the context of proof, Mill appeals to the logical tradition of western philosophy, going back to Aristotle. We can already find this dilemma of logical thought explicitly formulated in classical antiquity. Commenting on a passage from Aristotle’s Physics (193a3) that reads: “…to try to prove the obvious from the unobvious is the mark of a man incapable of distinguishing what is self-evident and what is not,” Simplicius wrote:

“…the words ‘the mark of a man incapable of distinguishing between what is self-evident and what is not’ typify the who who is anxious to prove by means of other things that nature, which is self-evident, is not self-evident. And it is even worse if they are to be proved by means of what is less knowable, which is what must happen in the case of things that are all too obvious. The man who wants to employ proof for everything eventually destroys proof. For if the evident must be the starting point of proof, the man who thinks that the evident needs proof no longer agrees that anything is evident, not does he leave any basis of proof, and so he leaves no proof either.”

Simplicius: On Aristotle Physics 2, translated by Barrie Fleet, London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 1997, p. 25

The axiological equivalence of self-evidence is intrinsic value, that is to say, self-value. The tradition of intrinsic value in English moral thought arguably reaches its apogee in G. E. Moore’s Principia Ethica, in which intrinsic value is a theme that occurs throughout the work:

“We must know both what degree of intrinsic value different things have, and how these different things may be obtained. But the vast majority of questions which have actually been discussed in Ethics—all practical questions, indeed—involve this double knowledge; and they have been discussed without any clear separation of the two distinct questions involved. A great part of the vast disagreements prevalent in Ethics is to be attributed to this failure in analysis. By the use of conceptions which involve both that of intrinsic value and that of causal relation, as if they involved intrinsic value only, two different errors have been rendered almost universal. Either it is assumed that nothing has intrinsic value which is not possible, or else it is assumed that what is necessary must have intrinsic value. Hence the primary and peculiar business of Ethics, the determination of what things have intrinsic value and in what degrees, has received no adequate treatment at all.”

G. E. Moore, Principia Ethica, section 17

The English, for the most part, had little affinity for Bergson, but it was Bergson who opened up moral philosophy to its temporal reality embedded in changing human experience. In several posts — Epistemic Space: Mapping Time and Object Disoriented Axiology among them — I have discussed Bertrand Russell’s antipathy to Bergson, even though Russell himself was once of the most powerful and passionate advocates of science, and it has been science that has forced us to put aside our equilibrium assumptions and to engage with a dynamic world that forces change upon us even if we would deny it.

The world as we understand it today, from the smallest quantum fluctuations to the evolution of the universe entire, is a dynamic world in which change is the only constant. In such a world, which our traditional eschatologies have invested with eternal moral significance, we would be better served by also abandoning equilibrium assumptions in ethics. There are trivial ways in which this occurs, as when we recognize that different objects have different moral values at different times; there are also more radical ways to think of a morally dynamic world, such as a world in which moral principles themselves must change.

Qualitative risk categories, Figure 2 from ‘Existential Risk Prevention as Global Priority’ (2012) Nick Bostrom

In Bostrom’s qualitative categories of risk, the risks of greatest scope are identified as trans-generational and pan-generational (with the possibility of a risks of cosmic scope also noted). Both the idea of the trans-generational and the pan-generational are essentially categories of intrinsic value over time. when existential risks of smaller scope are considered, they are limited to personal, local, or global circumstances. These smaller, local risks when understood in contradistinction to trans-generational and the pan-generational can also be seen as instances of intrinsic value over time, through shorter periods of time appropriate to personal time, social time, or global time.

While it is gratifying to see this recognition of intrinsic value over time, we can go farther by considering the natural history of value. The simple and fundamental lesson of the natural history of value is that value changes over time, and that particular objects may be the bearers of intrinsic value for a temporary period of time, taking on this value and then ultimately surrendering it. Moreover, intrinsic value itself changes over time, as do the forms in which it is manifested and embodied.

When Sartre gave his famous lecture “Existentialism is a Humanism,” he took the bull by the horns and faced straight on the claims that had been made that existentialism was a gloomy philosophy of despair, quietism, and pessimism. Of his critics Sartre said, “what is annoying them is not so much our pessimism, but, much more likely, our optimism. For at bottom, what is alarming in the doctrine that I am about to try to explain to you is — is it not? — that it confronts man with a possibility of choice.” For Sartre, existentialism is, at bottom, an optimistic philosophy because it affirms the reality of choice and human agency. And so, too, the recognition of the natural history of value — that value is not a fixed and unchanging feature of the world — is an optimistic doctrine preferable to any and all false hopes.

Questioning ancient moral prejudices, as Sartre often did, almost always results in claims on behalf of traditionalists that the sky is falling, and that by opening Pandora’s Box we have unleashed evils into the world that cannot be contained. But to observe that intrinsic value changes over time is no counsel of despair, as when Bertrand Russell (as I recently quoted in Developing an Existential Perspective) said that, “…only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.” That intrinsic value is subject to change means that the intrinsic value of the world may increase or decrease, and if it may increase, we ourselves may be the agents of this change.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Two Models of Perspective Taking

20 September 2013

Friday

What happens when an individual achieves a new level of perspective taking? Is one perspective displaced by another? Is a new perspective added to existing perspectives?

Firstly, what do I mean by “perspective taking” in this context? In a couple of posts I’ve discussed perspective taking as a theme of developmental psychology — The Hierarchy of Perspective Taking and The Overview Effect as Perspective Taking — but I haven’t tried to rigorously define it. The short version is that perspective taking is putting yourself in the position of the other and seeing the world from the other’s point of view (or perspective, hence perspective taking). This is, as I have previously remarked, one of the most basic thought experiments in moral philosophy.

Kant implicitly appeals to perspective taking in his categorical imperative, in which he asserts that one ought to act as though the principle that guides one’s actions should be made a universal law. In other words, you ask yourself, “What would the consequences be if everyone acted as I am acting?” This, in turn, supposes that one can place oneself into the position of the other and imagine how the principle of your action would be interpreted and put into practice by others.

It could also be argued that Kant’s categorical imperative is implicit in the regime of popular sovereignty, which has its origins in Kant’s time but which only in the twentieth century became the universally acclaimed normative standard for political entities. Everyone knows that their individual vote does not count, because if you subtracted your vote from the total in any election, it would not affect the outcome. Nevertheless, if everyone came to this conclusion and acted upon it, no one would vote and democracy would collapse.

To return to perspective taking, there are much more sophisticated formulations than the off-the-cuff version I have given above. There is an interesting paper that discusses the conception of perspective taking — THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOCIO-MORAL MEANING MAKING: DOMAINS, CATEGORIES, AND PERSPECTIVE-TAKING — the authors of which, Monika Keller and Wolfgang Edelstein, converge on this definition:

“…perspective-taking is taken to represent the formal structure of coordination of the perspectives of self and other as they relate to the different categories of people’s naive theories of action. The differentiation and coordination of the categories of action and the self-reflexive structure of this process are basic to those processes of development and socialization in which children come to reconstruct the meaning of social interaction in terms of both what is the case and what ought to be the case in terms of morally responsible action. In order to achieve the task of establishing consent and mutually acceptable lines of action in situations of conflicting claims and expectations, a person has to take into account the intersubjective aspects of the situation that represent the generalizable features, as well as the subjective aspects that represent the viewpoints of the persons involved in the situation. In its fully developed form, this complex process of regulation and interaction calls for the existence and operation of complex socio-moral knowledge structures and a concept of self as a morally responsible agent. The ability to differentiate and coordinate the perspectives of self and other thus is a necessary condition both in the development of socio-moral meaning making and in the actual process of solving situations of conflicting claims.”

“THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOCIO-MORAL MEANING MAKING: DOMAINS, CATEGORIES, AND PERSPECTIVE-TAKING,” by Monika Keller and Wolfgang Edelstein, in W. M. Kurtines & J. L. Gewirtz (Eds.) (1991). Handbook of moral behavior and development: Vol. 2. Research (pp. 89-114). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

I recommend the entire paper, which discusses, among other matters, the attempts by others to formulate an adequate explication of perspective taking. But I have an ulterior motive for this discussion of perspective taking. The real reason I have engaged in this inquiry about perspective taking is because of my recent posts about the overview effect — The Epistemic Overview Effect and The Overview Effect as Perspective Taking — in which I treat the overview effect as a visceral trigger for perspective taking on a global (and even trans-planetary) scale.

Thinking about the overview effect as perspective taking, I considered the possibility that taking a new global or even trans-planetary perspective might involve either dispensing with a former perspective in order to replace it with a novel perspective (which I will call the displacement model), or adding a new perspective to already existing perspectives (which I will call the augmentation model). (And here I want to cite Siggi Becker and Mark Lambertz, who commented on my earlier overview effect post on Facebook, and spurred me into thinking about what it means for one to achieve a new perspective on the world.)

For cognitive scientists and sociologists, perspective taking is cumulative, especially in the case of moral development. There is an entire literature devoted to Robert L. Selman’s five stages of perspective taking (which is very much influenced by Piaget) and Lawrence Kohlberg’s six stages of moral development (three stages — pre-conventional, conventional and post-conventional — each broken into two divisions).

There are, however, definite limits to this Piagetian cognitive basis for the development of the moral life of the individual. Without some degree of empathy for the other, all of this cognitive approach to moral development falls apart, because one might systematically pursue the development of one’s perspective taking ability only to more successfully exploit and manipulate others through a more effective cunning than that provided by a purely egocentric approach to interaction with others. Thus we arrive at the Schopenhauerian conception such that compassion is the basis of morality.

Max Scheler systematically critiqued this classic Schopenhauerian position in his book The Nature of Sympathy. Scheler concluded that compassion alone is insufficient for morality, thus undermining Schopenhauer’s position, but that compassion alone may not be a sufficient condition for morality, it may yet be a necessary condition. Perhaps it is compassion and perspective taking together that make morality possible. These philosophical issues have also been taken up in the spirit of social science by Carol Gilligan’s work on the ethics of care. I only touch on these issues here in passing, since any serious consideration of these works and their authors would require substantial exposition.

Perspective taking is central to Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of moral development, and what Kohlberg calls “disequilibrium” (which serves as a spur to moral development) might also be called “disorientation,” or, more specifically, “moral disorientation.” And it is disorienting when one achieves a new perspective, and especially when one does as suddenly, as in the case of the visceral trigger provided by the overview effect. Plato describes such a disorienting experience beautifully in his famous allegory of the cave — the philosopher is twice disoriented, initially as he ascends from the cave of shadows up into the real world, and again when we descends again into the cave of shadows in order to attempt to enlighten those still chained below. A power experience leaves one feeling disoriented, and much of this disorientation is due to the collapse of a familiar system of thought that gave one a sense of one’s place in the world, and its replacement by a new system of thought that is not yet familiar.

If we focus too much on cumulative and continuous aspects of perspective taking, on the assumption that each level of development must build upon the immediately previous level, we may lose sight of the disruptive nature of perspective taking — and moral development is not a primrose path. As individuals confront moral dilemmas they are forced to consider difficult question and sometimes to give hard answers to difficult questions. This is central to the moral growth of the person, and it is often quite uncomfortable and attended by anxiety and inner conflict. One often feels that one fights one’s way through a problem, only to surmount it. This is very much like Wittgenstein’s description of throwing away the ladder once one has climbed up.

If the overview effect constitutes a new level of perspective taking, and if perspective taking is central to moral development, then the perspective taking of the overview effect constitutes a stage in human moral development — and it constitutes that stage of moral development that coincides with civilization’s expansion beyond terrestrial boundaries.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Freedom and Ressentiment

1 September 2013

Sunday

Sometimes when I am asked my favorite book I reply that it is Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals, which is the most systematic of his books on ethics and which gives his most detailed exposition of ressentiment. I reread the third essay in the book today — “What is the meaning of ascetic ideals?” — keeping in mind while I did what I wrote about freedom day before yesterday in Theory and Practice of Freedom.

To give a flavor of Nietzsche’s argument I want to cite a couple of passages from the book that I take to be particularly crucial. Firstly, here is the passage in which Nietzsche introduces the idea of ressentiment becoming creative and creating its own values:

“The beginning of the slaves’ revolt in morality occurs when ressentiment itself turns creative and gives birth to values: the ressentiment of those beings who, denied the proper response of action, compensate for it only with imaginary revenge. Whereas all noble morality grows out of a triumphant saying ‘yes’ to itself, slave morality says ‘no’ on principle to everything that is ‘outside’, ‘other’, ‘non-self ’: and this ‘no’ is its creative deed.”

Nietzsche, Friedrich, On the Genealogy of Morality, EDITED BY KEITH ANSELL-PEARSON, Department of Philosophy, University of Warwick, TRANSLATED BY CAROL DIETHE, Cambridge University Press, 1994, 2007, p. 20

Near the end of the book, Nietzsche reiterates one of his central themes, that man would rather will nothing than not will:

“It is absolutely impossible for us to conceal what was actually expressed by that whole willing that derives its direction from the ascetic ideal: this hatred of the human, and even more of the animalistic, even more of the material, this horror of the senses, of reason itself, this fear of happiness and beauty, this longing to get away from appearance, transience, growth, death, wishing, longing itself — all that means, let us dare to grasp it, a will to nothingness, an aversion to life, a rebellion against the most fundamental prerequisites of life, but it is and remains a will! …And, to conclude by saying what I said at the beginning: man still prefers to will nothingness, than not will…”

Nietzsche, Friedrich, On the Genealogy of Morality, EDITED BY KEITH ANSELL-PEARSON, Department of Philosophy, University of Warwick, TRANSLATED BY CAROL DIETHE, Cambridge University Press, 1994, 2007, p. 120

One of the themes that occurs throughout Nietzsche’s works is the critique of nihilism — Nietzsche finds nihilism in much that others fail to recognize as such, while Nietzsche himself has been accused of nihilism because of his iconoclasm. The immediately preceding passage strikes me as one of Nietzsche’s most powerful formulations of unexpected and unrecognized nihilism: willing nothing.

I think Nietzsche primarily had institutional religion in mind, especially those institutionalized religions that put a priestly caste in power (whether directly or indirectly), but there are plenty of examples of thoroughly secular forms of ressentiment developing to the point of creating its own values, and I think one of the principal forms of secular ressentiment takes the form of the denial or the repudiation or the rejection of freedom. The denial of freedom is a particularly pure form of the nihilistic will saying “No!” to life, since life, in the living of it, is all about freedom — we realize our freedom in the dizziness that is dread, and make our choices in fear and trembling. Many people quite literally become physically ill when faced with a momentous choice — so great a role does the idea of freedom play in our thoughts, that our thoughts are manifested physically.

The denial of freedom takes many forms. For example, it often takes the form of determinism, and determinism itself can take many forms. On my other blog I wrote about determinism from the point of view of the denial of freedom as a philosophical problem — something I wanted to do to counter the prevalent attitude that asks why so many people believe in their own freewill. This approach seems to me incredibly perverse, and the more reasonable question is to ask why so many people believe they do not have freewill. Now, Nietzsche himself was a determinist, so he likely would not be sympathetic to what I’m saying here, but that does not stop us from applying Nietzsche’s own ideas to himself (something Max Scheler also did in his book on Ressentiment).

Probably the most common form that the denial of freedom takes is a rationalization of a failure to take advantage of one’s freedoms. This is a much more subtle denial of freedom than determinism, and in fact assumes the reality of free will. If the palpable reality of freedom, and the potential upsets to the ordinary business of life that it presents, were not all-too-real, there would be no need to formulate elaborate rationales for not taking advantage of one’s freedom and opting for a life of conformity and servile acquiescence to authority.

Understanding that freedom is honored more in the breach than the observance was a well-trodden path in twentieth century thought. Although Freud had deterministic sympathies, his theories of reason as the mere rationalization of what the unconscious was going to do anyway incorporates both determinist and free willist assumptions. The denial of freedom is a central theme in Sartre’s work (the spirit of seriousness and the idea of bad faith are both important forms of the denial of freedom), and through Freud and Sartre the influence on twentieth century thought and literature was profound. I have previously cited the role of Gooper Pollitt in Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof as a paradigm of inauthenticity (in Existential Due Diligence).

All one need do is look around at the world we’ve made, with all its laws and statutes, its codes and regulations, its institutions and rules, its traditions and customs — it would be entirely possible to pass an entire lifetime in this context without realizing, much less exercising, one’s freedom. And these are only passive discouragements. When it comes to active discouragements to freedom, every nay-sayer, every pessimist, every wagging finger, every shaming tactic, every snide and cynical comment is an attempt to dissuade us from enjoying our freedom and entering into the same self-chosen misery of all those who have systematically extirpated all traces of freedom from their own lives.

Everyone who has given up freedom in their own life understandably resents seeing the exercise of freedom in the lives of others, and when this resentment turns creative it gives birth to every imaginable form of slander of freedom and of praise of servility — whether to a cause or to a movement or to an individual or to an institution — not to mention endless rationalizations of why the refusal of freedom isn’t really a refusal of freedom. Don’t believe it. Don’t believe any of it. Don’t buy into it. There is nothing in this world that is worth surrendering your freedom for — not matter how highly it is praised or how enthusiastically it is celebrated — this praise and this celebration of unfreedom is nothing but the creative response of ressentiment directed against freedom.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Moral Horror Fallacy

29 June 2013

Saturday

It is difficult to find an authentic expression of horror, due to its close resemblance to both fear and disgust, but one readily recognizes horror when one sees it.

In several posts I have referred to moral horror and the power of moral horror to shape our lives and even to shape our history and our civilization (cf., e.g., Cosmic Hubris or Cosmic Humility?, Addendum on the Avoidance of Moral Horror, and Against Natural History, Right and Left). Being horrified on a uniquely moral level is a sui generis experience that cannot be reduced to any other experience, or any other kind of experience. Thus the experience of moral horror must not be denied (which would constitute an instance of failing to do justice to our intuitions), but at the same time it cannot be uncritically accepted as definitive of the moral life of humanity.

Our moral intuitions tell us what is right and wrong, but they do not tell us what is or is not (i.e., what exists or what does not exist). This is the upshot of the is-ought distinction, which, like moral horror, must not be taken as an absolute principle, even if it is a rough and ready guide in our thinking. It is perfectly consistent, if discomfiting, to explicitly acknowledge the moral horrors of the world, and not to deny that they exist even while acknowledging that they are horrific. Sometimes the claim is made that the world itself is a moral horror. Joseph Campbell attributes this view to Schopenhauer, saying that according to Schopenhauer the world is something that never should have been.

Apart from the horrors of the world as a central theme of mythology, it is also to be found in science. There is a famous quote from Darwin that illustrates the acknowledgement of moral horror:

“There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent & omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidæ with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice.

Letter from Charles Darwin to Asa Gray, 22 May 1860

This quote from Darwin underlines another point repeatedly made by Joseph Campbell: that different individuals and different societies draw different lessons from the same world. For some, the sufferings of the world constitute an affirmation of divinity, while for Darwin and others, the sufferings of the world constitute a denial of divinity. That being said, it is not the point I would like to make today.

Far more common than the acceptance of the world’s moral horrors as they are is the denial of moral horrors, and especially the denial that moral horrors will occur in the future. On one level, a pragmatic level, we like to believe that we have learned our lessons from the horrors of our past, and that we will not repeat them precisely because we have perpetrated horrors in past and came to realize that they were horrors.

To insist that moral horrors can’t happen because it would offend our sensibilities to acknowledge such a moral horror is a fallacy. Specifically, the moral horror fallacy is a special case of the argumentum ad baculum (argument to the cudgel or appeal to the stick), which is in turn a special case of the argumentum ad consequentiam (appeal to consequences).

Here is one way to formulate the fallacy:

Such-and-such constitutes a moral horror,

It would be unconscionable for a moral horror to take place,

Therefore, such-and-such will not take place.

For “such-and-such” you can substitute “transhumanism” or “nuclear war” or “human extinction” and so on. The inference is fallacious only when the shift is made from is to ought or from ought to is. If confine our inference exclusively either to what is or what ought to be, we do not have a fallacy. For example:

Such-and-such constitutes a moral horror,

It would be unconscionable for a moral horror to take place,

Therefore, we must not allow such-and-such to take place.

…is not fallacious. It is, rather, a moral imperative. If you do not want a moral horror to occur, then you must not allow it to occur. This is what Kant called a hypothetical imperative. This is a formulation entirely in terms of what ought to be. We can also formulate this in terms of what is:

Such-and-such constitutes a moral horror,

Moral horrors do not occur,

Therefore, such-and-such does not occur.

This is a valid inference, although it is false. That is to say, this is not a formal fallacy but a material fallacy. Moral horrors do, in fact, occur, so the premise stating that moral horrors do not occur is a false premise, and the conclusion drawn from this false premise is a false conclusion. (If one denies that moral horrors do, in fact, take place, then one argues for the truth of this inference.)

Moral horrors can and do happen. They are even visited upon us numerous times. After the Holocaust everyone said “never again,” yet subsequent history has not spared us further genocides. Nor will it spare us further genocides and atrocities in the future. We cannot infer from our desire to be spared further genocides and atrocities that they will not come to pass.

More interesting than the fact that moral horrors continue to be perpetrated by the enlightened and technologically advanced human societies of the twenty-first century is the fact that the moral life of humanity evolves, and it often is the case that the moral horrors of the future, to which we look forward with fear and trembling, sometimes cease to be moral horrors by the time they are upon us.

Malthus famously argued that, because human population growth outstrips the production of food (and Malthus was particularly concerned with human beings, but he held this to be a universal law affecting all life) that humanity must end in misery or vice. By “misery” Malthus understood mass starvation — which I am sure that most of us today would agree is misery — and by “vice” Malthus meant birth control. In other words, Malthus viewed birth control as a moral horror comparable to mass starvation. This is not a view that is widely held today.

A great many unprecedented events have occurred since Malthus wrote his Essay on the Principle of Population. The industrialization of agriculture not only provided the world with plenty of food for an unprecedented increase in human population, it did so while farming was reduced to a marginal sector of the economy. And in the meantime birth control has become commonplace — we speak of it today as an aspect of “reproductive rights” — and few regard it as a moral horror. However, in the midst of this moral change and abundance, starvation continues to be a problem, and perhaps even more of a moral horror because there is plenty of food in the world today. Where people are starving, it is only a matter of distribution, and this is primarily a matter of politics.

I think that in the coming decades and centuries that there will be many developments that we today regard as moral horrors, but when we experience them they will not be quite as horrific as we thought. Take, for instance, transhumanism. Francis Fukuyama wrote a short essay in Foreign Policy magazine, Transhumanism, in which he identified transhumanism as the world’s most dangerous idea. While Fukuyama does not commit the moral horror fallacy in any explicit way, it is clear that he sees transhumanism as a moral horror. In fact, many do. But in the fullness of time, when our minds will have changed as much as our bodies, if not more, transhumanism is not likely to appear so horrific.

On the other hand, as I noted above, we will continue to experience moral horrors of unprecedented kinds, and probably also on an unprecedented scope and scale. With the human population at seven billion and climbing, our civilization may well experience wars and diseases and famines that kill billions even while civilization itself continues despite such depredations.

We should, then, be prepared for moral horrors — for some that are truly horrific, and others that turn out to be less than horrific once they are upon us. What we should not try to do is to infer from our desires and preferences in the present what must be or what will be. And the good news in all of this is that we have the power to change future events, to make the moral horrors that occur less horrific than they might have been, and to prepare ourselves intellectually to accept change that might have, once upon a time, been considered a moral horror.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Existential Risk and the Death Event

3 May 2013

Friday

Fourth in a Series on Existential Risk

“The human race’s prospects of survival were considerably better when we were defenceless against tigers than they are today, when we have become defenceless against ourselves.” Arnold Toynbee, “Man and Hunger” (Speech to the World Food Congress, 04 January 1963, quoted on the Anthropocene Blog)

Readers, I trust, will be aware of existential risks (as well as global catastrophic risks) since I’ve recently written several recent posts on this topic, including Research Questions on Existential Risk, Six Theses on Existential Risk, Existential Risk Reminder, Moral Imperatives Posed by Existential Risk, Existential Risk and Existential Uncertainty, and Addendum on Existential Risk and Existential Uncertainty. The idea of the “Death Event” is likely to be much less familiar, so I will try to sketch out the idea itself and its relationship to existential risk.

The idea of the “death event” is due to philosopher Edith Wyschogrod, and given exposition in her book Spirit in Ashes: Hegel, Heidegger, and Man-Made Mass Death. Wyschogrod took the title of her book from an aphorism of Wittgenstein’s from 1930: “I once said, perhaps rightly: The earlier culture will become a heap of rubble and finally a heap of ashes, but spirits will hover over the ashes.”

In defining the scope of the “death event” Wyschogrod wrote:

“I shall define the scope of the event to include three characteristic expressions: recent wars which deploy weapons in the interest of maximum destruction of persons, annihilation of persons, through techniques designed for this purpose (for example, famine, scorched earth, deportation), after the aims of war have been achieved or without reference to war, and the creation of death-worlds, a new and unique form of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life simulating imagined conditions of death, conferring upon their inhabitants the status of the living dead.”

Edith Wyschogrod, Spirit in Ashes: Hegel, Heidegger, and Man-Made Mass Death, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1985, p. 15.

Wyschogrod’s conception of the “death world,” also given exposition in the text, is introduced in conscious contradistinction to the late Husserlian conception of the “Lifeworld” (Lebenswelt). (Cf. Chapter 1, Kingdoms of Death) I cannot do justice to Wyschogrod’s excellent book in a few quotes, so I will simply encourage the reader to look up the book for himself, but I will give a couple more quotes to locate the “death event” in relation to the larger picture of our civilization. Wyschogrod sees a relation between the “death event” and the peculiar character of industrial-technological civilization:

“The procedures and instruments of death which depend upon the quantification of the qualitied world are innovations deriving from technological society and, to that extent, extend its point of view.”

Op. cit., p. 25

And again,

“…the world of the camps is both distinct from and tied to technological society, so too the nuclear void is embedded in the matrix of technological society but not related to it in simple cause and effect fashion.”

Op. cit., p. 29

Perhaps at some future time I will consider Wyschogrod’s “death event” thesis in relation to what I have called Agriculture and the Macabre, which is the particular relationship between agricultural civilization and death, but whether or not the reader agrees with me or not (or with Wyschogrod, for that matter) I will acknowledge without hesitation that the character of the macabre in agricultural civilization is very different from the place of the death event and the death world in industrial-technological civilization.

Wyschogrod focuses on death camps and industrialized warfare, but of course what shocked the world more than anything were the nuclear bombs that ended the war. A considerable bibliography could be devoted to the books exclusively devoted to the anguished reflection that followed the atomic explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, many of them written by and about the scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project and made the bomb possible. Many of the most eminent philosophers of the time immediately began to think about the consequences — both contemporaneously and for the longer term human future — of human beings being in possession of nuclear weapons.

Bertrand Russell wrote two books on the possibility of nuclear war, Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare (1959) and Has Man a Future? (1961) Recently in Bertrand Russell as Futurist I discussed Russell’s views on the need for world government in order to prevent the annihilation of human life due to nuclear weapons — a view shared by Albert Einstein.

In 1958 Karl Jaspers published Die Atombombe und die Zukunft des Menschen, later translated into English as The Future of Mankind. What all of these works have in common is struggling with what Jaspers called “the new fact.” Of this new fact Jaspers wrote:

“The atom bomb of today is a fact novel in essence, for it leads mankind to the brink of self-destruction.”

Karl Jaspers, The Future of Mankind, Chap. I, p. 1

And…

“the atom bomb is today the greatest of all menaces to the future of mankind… The possible reality which we must henceforth reckon with — and reckon with, at the increasing pace of developments, in the near future — is no longer a fictitious end of the world. It is no world’s end at all, but the extinction of life on the surface of the planet.”

Op. cit., p. 4

The fact that fear of nuclear Armageddon was felt viscerally as an all-too-real possibility for our world points to the fact that this was not merely the appearance of a new idea in human history — new ideas appear every day — but a fundamental shift in feeling. When the awful reality of the Second World War, which saw man-made mass death on an unprecedented scale, received its finale in the form of the atomic blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we had acquired a new object for our instinctual fear of annihilation.

The larger meaning of the “death event” — testified not only in Edith Wyschogrod’s explicit formulation, but also in the work of Bertrand Russell, Karl Jaspers, and a hundred others — is that of formal, reflexive consciousness of anthropogenic existential risk. We not only know that we are vulnerable to existential risk, we also know that we know. It is this formal, reflexive self-consciousness of existential risk that is the differentia between human history before the “death event” and human history after the “death event.” The “death event” was a crystallizing event, a particular moment in history that was a watershed for human suffering that placed that suffering in the naturalistic context.

Earlier catastrophes in human experience did not have this character — or, if they did have this character for a few individuals who realized the larger meaning of events, this formal, reflexive consciousness of human vulnerability did not achieve general recognition. Partly this was a consequence of the non-naturalistic and teleological assumptions that were integral with the outlook of earlier epochs of human civilization, before science made a naturalistic conception of the world entire conceivable. If one believes that a supernatural force will intervene to continue to maintain human beings in existence, there is no reason to be concerned with the possibility of human extinction.

Prior to industrial-technological civilization (made possible by the scientific revolution, which is particularly relevant in this context), the “end of the world” could only be understood in eschatological terms because eschatologies derived from theological cosmogonies were the only “big picture” accounts of the cosmos that had been formulated and which had achieved any degree of currency. (There have always been non-theological philosophical cosmogonies, but these have remained marginal throughout human history.)

Until science provided an alternative, the only big picture conceptions of the world were traditional cosmogonies, to which the least imaginative among us still recur.

The situation in regard to “big picture” conceptions of the world is closely parallel to that of biology prior to Darwin’s theory of natural selection: there were no strictly biological theories of biology prior to Darwin, only theological theories that were employed to “explain” biological facts. With no alternative to a theological account of biology, it is to be expected that this sole point of view was the universal point of reference, just as where there is no alternative to the theological account of history, this theological account is the sole point of reference in history.

Charles Darwin, in formulating a thorough-going scientific biology, gave the world its first non-theological formulation of biology.