Technological Civilization: Part I

10 June 2018

Sunday

What is a technological civilization?

For lack of better terminology and classifications, we routinely refer to “technical civilizations” or “technological civilizations” in discussions of SETI and more generally when discussing the place of civilization in the cosmos. One often sees the phrase advanced technological civilizations (sometimes abbreviated “ATC,” as in the paper “Galactic Gradients, Postbiological Evolution and the Apparent Failure of SETI” by Milan M. Ćirković and Robert J. Bradbury). Martyn J. Fogg has used an alternative phrase, “extraterrestrial technical civilizations (ETTCs)” (in his paper “Temporal aspects of the Interaction among the First Galactic Civilizations: The ‘lnterdict Hypothesis’”) that seems to carry a similar meaning to “advanced technological civilizations.” Thus the usage “technological civilization” is fairly well established, but its definition is not. What constitutes a technological civilization?

A model of civilization applied to the problem of technological civilization

In formulating a model of civilization — an economic infrastructure joined to an intellectual superstructure by a central project — I have a schematism by which a given civilization can be analyzed into constituent parts, and this makes it possible to lay out the permutations of the relationship of some human activity to the constituents of civilization, and the role that the human activity in question plays in the constitution of these constituents. Recently I have done this for spacefaring civilization (in Indifferently Spacefaring Civilizations) and for scientific civilization (in Science in a Scientific Civilization). A parallel formulation for technological civilization yields the following:

0. The null case: technology is not present in any of the elements that constitute a given civilization. This is a non-technological civilization. We will leave the question open as to whether a non-technological civilization is possible or not.

1. Economically technological civilization: technology is integral only to the economic infrastructure, and is absent elsewhere in the structures of civilization; also called intellectually indifferent technological civilization.

2. Intellectually technological civilization: technology is integral only to the intellectual superstructure of civilization, and is absent elsewhere in the structures of civilization; also called economically indifferent technological civilization.

3. Economically and intellectually technological civilization: technology is integral to both the economic infrastructure and the intellectual superstructure of a civilization, but is absent in the central project; also known as morally indifferent technological civilization.

4. Properly technological civilization: technology is integral to the central project of a civilization.

There are three additional permutations not mentioned above:

● Technology constitutes the central project but is absent in the economic infrastructure and the intellectual superstructure.

● Technology is integral with the central project and economic infrastructure, but is absent in the intellectual superstructure.

● Technology is integral with the central project and intellectual infrastructure, but is absent in the economic infrastructure.

These latter three permutations are non-viable institutional structures and must be set aside. Because of the role that a central project plays in a civilization, whatever defines the central project is also, of necessity, integral to economic infrastructure and intellectual superstructure.

In the case of technology, some of the other permutations I have identified may also be non-viable. As noted above, a non-technological civilization may be impossible, so that the null case would be a non-viable scenario. More troubling (from a technological point of view) is that technology itself may be too limited of an aspect of the human condition to function effectively as a central project. If this were the case, there could still be technological civilizations in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd senses given above, but there would be no properly technological civilization (as I have defined this). Is this the case?

Can technology function as the central project of a civilization?

At first thought technology would seem to be an unlikely candidate for a viable central project, but there are several ways in which technology could be integral in a central project. Spacefaring is a particular technology; virtual reality is also a particular technology. Presumably civilizations that possess these technologies and pursue them as central projects (either or both of them) are properly technological civilizations, even if the two represent vastly different, or in same cases mutually exclusive, forms of social development. Civilizations that take a particular technology as their central project by definition have technology as their central project, and so would be technological civilizations. For that matter, the same can be said of agriculture: agriculture is a particular technology, and so agricultural civilizations are technological civilizations in this sense.

A scientific civilization such as I discussed in Science in a Scientific Civilization would have technology integral with its central project, in so far as contemporary science, especially “big science,” is part of the STEM cycle in which science develops new technologies that are engineered into industries that supply tools for science to further develop new technologies. Technological development is crucial to continuing scientific development, so that a scientific civilization would also be a technological civilization.

In both of these examples — technological civilizations based on a particular technology, and technological civilizations focused on science — technology as an end in itself, technology for technology’s sake, as it were, is not the focus of the central project, even though technology is inseparable from the central project. Within the central project, then, meaningful distinctions can be made in which a particular element that is integral to the central project may or may not be an end in itself.

Technology as an end in itself

For a civilization to be a properly technological civilization in the sense that technology itself was an end in itself — a civilization of the engineers, by the engineers, and for the engineers, you could say — the valuation of technology would have to be something other than the instrumental valuation of technology as integral to the advancement of science or as the conditio sine qua non of some particular human activity that requires some particular technology. Something like this is suggested in Tinkering with Artificial Intelligence: On the Possibility of a Post-Scientific Technology, in which I speculated on technology that works without us having a scientific context for understanding how it works.

If the human interest were there to make a fascination with such post-scientific technologies central to human concerns, then there would be the possibility of a properly technological civilization in the sense of technology as an end in itself. Arguably, we can already see intimations of this in the contemporary fascination with personal electronic devices, which increasingly are the center of attention of human beings, and not only in the most industrialized nation-states. I remember when I was visiting San Salvador de Jujuy (when I traveled to Argentina in 2010), I saw a street sweeper — not a large piece of machinery, but an individual pushing a small garbage can on wheels and sweeping the street with a broom and a dustpan — focused on his mobile phone, and I was struck by the availability of mobile electronic technologies to be in the hands of a worker in a non-prestigious industry in a nation-state not in the top 20 of global GDP. (San Salvador de Jujuy is not known as place for sightseeing, but the city left a real impression on me, and I had some particularly good empanadas there.)

This scenario for a properly technological civilization is possible, but I still do not view it as likely, as most people do not have an engineer’s fascination with technology. However, it would not be difficult to formulate scenarios in which a somewhat richer central project that included technology as an end in itself, along with other elements that would constitute a cluster of related ideas, could function in such a way as to draw in the bulk of a society’s population and so function as a coherent social focus of a civilization.

Preliminary conclusions

Having come thus far in our examination of technological civilizations, we can already draw some preliminary conclusions, and I think that these preliminary conclusions again point to the utility of the model of civilization that I am employing. Because a properly technological civilization seems to be at least somewhat unlikely, but indifferently technological civilizations seem to be the rule, and are perhaps necessarily the rule (because technology precedes civilization and all civilizations make use of some technologies), the force of the ordinary usage of “technological civilization” is not to single out those civilizations that I would say are properly technological civilizations, but rather to identify a class of civilizations in which technology has reached some stage of development (usually an advanced stage) and some degree of penetration into society (usually a pervasive degree).

How this points to the utility of the model of civilization I am employing is, firstly, to distinguish between properly technological civilizations and indifferently technological civilizations, to know the difference between these two classes, and to be able to identify the ordinary usage of “technological civilization” as the intersection of the class of all properly technological civilizations and the class of all indifferently technological civilizations. Secondly, the model of civilization I am employing allows us to identify classes of civilization based not only upon shared properties, but also upon the continuity of shared properties over time, even when this continuity bridges distinct civilizations and may not single out any one civilization.

In the tripartite model of civilization — as above, an economic infrastructure joined to an intellectual superstructure by a central project — technology and technological development may inhere in any one or all three of these elements of civilization. The narrowest and most restrictive definition of civilization is that which follows from the unbroken continuity of all three elements of the tripartite model: a civilization begins when all three identified elements are present, and it ends when one or more elements fail or change. With the understanding that “technological civilization” is not primarily used to identify civilizations that have technology as their central project, but rather is used to identify the scope and scale of technology employed in a given civilization, this usage does not correspond to the narrowest definition of civilization under the tripartite model.

Significance for the study of civilization

We use “technological civilization” much as we may use labels like “western civilization” or “European civilization” or “agricultural civilization,” and these are not narrow definitions that single out particular individual civilizations, but rather broad categories that identify a large number of distinct civilizations, i.e., under the umbrella concept of European civilizations we might include many civilizations in the narrowest sense. For example, Jacob Burckhardt’s famous study The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy identifies a regional civilization specific to a place and a time. This is a civilization defined in the narrowest sense. There are continuities between the renaissance civilization in Italy and our own civilization today, but this is a continuity that falls short of the narrowest definition of civilization. Similarly, the continuity of those civilizations we would call “technological” falls short of the narrowest possible definition of a technological civilization (which would be a properly technological civilization), but it is a category of civilization that may involve the continuity of technology in the economic infrastructure, continuity of technology in the intellectual superstructure, or both.

The lesson here for any study of civilization is that “civilization” means different things even though we do not yet have a vocabulary to distinguish the different senses of civilization as we casually employ the term. We may speak of “the civilization of the renaissance in Italy” (the narrowest conception of civilization) in the same breath that we speak of “technological civilization” (a less narrow conception) though we don’t mean the same thing in each case. To preface “civilization” with some modifier — European, western, technological, renaissance — implies that each singles out a class of civilizations in more-or-less the same way, but now we see that this is not the case. The virtue of the tripartite model is that it gives us a systematic method for differentiating the ways in which classes of civilizations are defined. It only remains to formulate an intuitively accessible terminology in order to convey these different meanings.

Looking ahead to Part II

In the case of SETI and its search for technological civilizations (which is the point at which I started this post), the continuity in question would not be that of historical causality, but rather of the shared properties of a category of civilizations. What are these shared properties? What distinguishes the class of technological civilizations? How are technological civilizations related to each other in space and time? We will consider these and other questions in Part II.

. . . . .

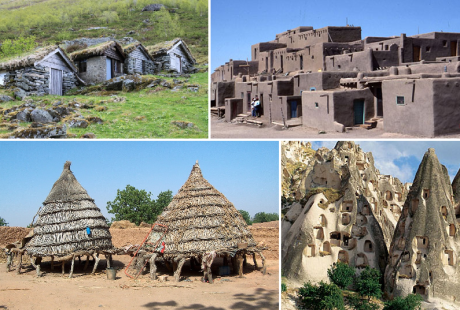

This is technological civilization after the industrial revolution, though we don’t think of this as “high” technology; this will be discussed in Part II.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Addendum on the Technocentric Thesis

12 October 2016

Wednesday

Biocentrism in an extended sense

In my recent post The Technocentric Thesis I formulated the latter idea such that all technocentric civilizations begin as biocentric civilizations and are transformed into technocentric civilizations through the replacement of biological constituents with technological constituents. This technocentric thesis implicitly refers to the anterior biocentric thesis, such that all civilizations in our universe begin as biocentric civilizations originating on planetary surfaces (in its strong form) or all civilizations during the Stelliferous Era begin as biocentric civilizations originating on planetary surfaces (in its weak form).

The technocentric thesis may be considered a generalization from the biocentric thesis (or, at least, an extension of the biocentric thesis), in so far as I previously argued in Astrobiology is island biogeography writ large that “spaceflight is to astrobiology as flight is to biogeography” which entails, in regard to the continuity of civilization and natural history, that “technology is the pursuit of biology by other means.” Thus technocentric civilizations continue imperatives of biocentric civilization, but by means other than biocentric means, i.e., by technological rather than biological means. Throughout the process of the replacement of the biological constituents of civilization by technological constituents of civilization, the imperatives of civilization remain intact and continuous.

We can make other generalizations from (and extensions of) the biocentric thesis. I wrote about a generalization of biophilia to non-terrestrial life in The Scope of Biophilia: “[E.O.] Wilson has already anticipated the extrapolation of biophilia beyond terrestrial life. Though Wilson’s term biophilia has rapidly gained currency and has been widely discussed, his original vision embracing a biophilia not limited to Earth has not enjoyed the same level of interest.” Here is the passage in question of E. O. Wilson’s Biophilia:

“From infancy we concentrate happily on ourselves and other organisms. We learn to distinguish life from the inanimate and move toward it like moths to a porch light. Novelty and diversity are particularly esteemed; the mere mention of the word extraterrestrial evokes reveries about still unexplored life, displacing the old and once potent exotic that drew earlier generations to remote islands and jungled interiors.”

Human Biophilia in its initial sense is the affinity that human beings have for the terrestrial biosphere, and the obvious extension of human biophilia (suggested in the passage quoted above from Wilson) would be the affinity that human beings may have for any life whatsoever in the cosmos, terrestrial or extraterrestrial. Might this hold generally for all biological beings, such that we can posit the affinity that some non-terrestrial biological being might have for the life of its homeworld, and the affinity that some non-terrestrial biological being might have for all life, including life on Earth (the mirror image of human biophilia in an extended sense)? These are the exobiological senses of biophilia (exobiophilia, if you like, or xenobiophilia).

These mirror image formulations of human biophilia and biophilia on the part of other intelligent (biological) agents suggests a more comprehensive formulation yet, that of the affinity of any biological being for any biology to be found anywhere in the universe. The presumed affinity that each biological organism will have for the biota of its homeworld involves the existential necessity of an organism’s attachment to the biota of its homeworld on the one hand, while on the other hand there is biophilia as a moral phenomenon, i.e., a constituent in the moral psychology of any biological being, the cognitive expression (or cognitive bias) of biocentrism. Biophilia in this formal sense would be the affinity that any biological being would have for the biota of its homeworld, while this formal biophilia in a generalized sense would be the affinity that any biological being would have for any life whatsoever in the cosmos.

How comprehensive is the scope of biophilia, or how comprehensive can it be, or ought it to be? Can we meaningfully extrapolate the concept of biophilia to such comprehensive scope as to include life on other worlds? I have formulated several thought experiments — Terrestrial Bias, Astrobiology Thought Experiment, and The Book of Earth — to investigate our intuitions in regard to other life, both on Earth and elsewhere. It would be an interesting project to follow up on these thought experiments more systematically as a research program in experimental philosophy. For the moment, however, I remain confined to thought experiments.

There are at least two forces counterbalancing the possibility of an expansive biophilia, with a scope exceeding that of terrestrial biology:

1) biophobia, and…

2) in-group bias

Parallel to biophilia there is biophobia, which is as instinctual as the former. Just as human beings have an affinity for certain life forms, we also have an instinctive fear of certain life forms. Indeed, the biosphere could be divided up into forms of life for which we possess biophilia, forms of life for which we possess biophobia, and forms of life to which we are indifferent. Biophobia, like biophilia, can be extrapolated as above to extraterrestrial forms of life. If and when we do find life elsewhere in the universe, no doubt some of this life will inspire us with awe and wonder, while some of its will inspire us with fear, perhaps even with palpable terror. So the scope of biophilia is modified by the parallel scope of biophobia. Given that terrestrial life is going to be more like us, while alien life will be less like us, I would guess that any future alien life will, on balance, inspire greater biophobia, while terrestrial life will, on balance, inspire greater biophilia. If this turns out to be true, the extension of biophilia beyond life of the terrestrial biosphere will be severely limited.

There is a pervasive in-group bias that marks eusociality in complex life, i.e., life sufficiently complex to have evolved consciousness, and perhaps also among eusocial insects, which are not likely to possess the kind of consciousness possessed by large brained mammals. I am using “eusocial” here in E. O. Wilson’s sense, as I have been reading E. O. Wilson’s The Social Conquest of Earth, in which Wilson contrasts the eusociality of insects and of human beings and a few other mammals. Wilson finds eusociality to be a relatively rare adaptive strategy, but also a very powerful one once it takes hold. Wilson credits human eusociality with the human dominance of the terrestrial biosphere today.

Wilson’s conception of eusociality among primates has been sharply rejected by many eminent biologists, among then Richard Dawkins and Stephen Pinker. The debate over eusociality in primates has focused on group selection (long a controversial topic in evolutionary biology) and the absence of reproductive division of labor in human beings. But the fact that one communication in criticism of Wilson and co-authors to the eminent scientific journal Nature (“Inclusive fitness theory and eusociality” Nature, 2011 March 24; 471, 7339: E1-4; author reply E9-10. doi: 10.1038/nature09831) had 134 signatures indicates that something more than the dispassionate pursuit of knowledge is involved in this debate. I am not going to attempt to summarize this debate here, but I will say only that I find value in Wilson’s conception of eusociality among human beings, and that the criticism of Wilson’s position has involved almost no attempt to understand Wilson’s point sympathetically.

Wilson had, of course, previously made himself controversial with his book on sociobiology, which discipline has subsequently been absorbed into and transformed into evolutionary psychology (one could say that sociobiology is evolutionary psychology in a nascent and inchoate stage of development), which continues to be controversial today, primarily because it says unflattering things about human nature. Wilson has continued to say unflattering things about human nature, and his treatment of human eusociality in The Social Conquest of Nature entails inherent human tribalism, which in turn entails warfare. This is not a popular claim to make, but it is a claim that resonates with my own ideas, as I have many times argued that civilization and war are coevolutionary; Wilson pushes this coevolutionary spiral of (in-group) sociality and (out-group) violence into the prehistoric, evolutionary past of humanity. With this I completely concur.

In-group bias and out-group hostility parallel each other in a way very much like biophilia and biophobia, and we could once again produce parallel formulations for extrapolating these human responses to worlds beyond our own — and perhaps also to other intelligent agents, so that these responses are not peculiarly human. How large can the scope of in-group bias become? It is a staple of many science fiction stories that human beings, divided against each other, unify to fight a common extraterrestrial enemy. I suspect that this would be true, and that in-group bias could be expanded even farther into the universe, but it would never be without the shadow of an out-group, however that out-group came to be defined, whether as other human beings who had abandoned Earth, or another species sufficiently different from us so as to arouse our suspicion and distrust.

There is a little known essay by Freeman Dyson that touches of themes of intrinsic human tribalism that are very much in the vein of Wilson’s argument, though Dyson’s article is many decades old, from the same year that human beings landed on the moon: “Human Consequences of the Exploration of Space” (Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Sept. 1969, Vol. XXV, No. 7; I was unable to find this article available on the internet, so I obtained a copy through interlibrary loan… many thanks to the Multnomah County Library System). In this article Dyson considers the problem of people in small groups, and in particular he describes how intrinsic human tribalism (i.e., in-group bias) might be exapted for a better future:

“…the real future of man in space lies far away from planets, in isolated city-states floating in the void, perhaps attached to an inconspicuous asteroid of perhaps to a comet… most important of all for man’s future, there will be groups of people setting out to find a place where they can be safe from prying eyes, free to experiment undisturbed with the creation of radically new types of human beings, surpassing us in mental capacities as we surpass the apes… So I foresee that the ultimate benefit of space travel to man will be to make it possible for him once again to live as he lived throughout prehistoric time, in isolated small units. Once again his human qualities of clannish loyalty and exclusiveness will serve a constructive role…”

Once again, I completely concur, though this is not the whole story. One of the greatest demographic trends of our time is urbanization, and we have seen millions upon millions move from rural areas and small towns into the always growing cities, both for their opportunities and their intrinsic interest. So human beings possess these tribal instincts that Dyson would harness for the good, but also eusocial instincts that flower in the world’s megacities, which are centers of both economic and intellectual innovation. Thus I find much of value in Dyson’s vision, but I would supplement it with the occasional conurbation, and I would assume that, over the course of an individual’s life, that there would be times that they would prefer the isolated community, times when they would prefer urban life, and times when they would want to leave all human society behind and immerse themselves in wilderness and wildness — perhaps even in the wilderness of an alien biosphere.

All of the things I have been describing here are essentially biological visions of the human future, which suggest that biocentric civilization still has many ways that it can grow and evolve, even if it does not converge on a form implied by the technocentric thesis, in which biology is displaced by technology. Technology can replace biology, and, when it does, the ends of biocentric civilization come to served by technological means, but that technology can replace biology does not mean that technology will replace biology.

Perhaps one of the sources of our technophilia is that we tend to think in technological terms because technology attains its ends over human scales of time, even over the scale of time of the individual human life and the individual human consciousness. But what technology can do quickly, biology can also do, more slowly, over biological and geological scales of time. If human civilization should be wiped away by any number of catastrophes that await us, the technological path of development will be foreclosed, but the biological path to development will still continue to be open as long as life exists, though it will operate over a scale of time that human beings do not perceive and mostly do not comprehend.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Technocentric Thesis

6 October 2016

Thursday

A biological being among biological beings

A human being is a being among beings, and moreover a biological being among biological beings. We come to an awareness of ourselves, and of what we are, in a biological context. Biophilia, then, is a default consequence of being biological and finding oneself in a biological content; biophilia is a cognitive bias of biological beings. (Previously I considered the relationship between our biological nature and our biological bias in Biocentrism and Biophilia.) From both our biocentrism and our biophilia follows biocentric civilization, which I formulated in terms of the biocentric thesis, so it is natural that I would next attempt to formulate a technocentric thesis, as I have often contrasted biocentric and technocentric conceptions.

Until quite recently there was no possibility of pursing a non-biophilic bent, i.e., of pursuing a technocentric bent. Over the past several thousand years of human civilization, individual human beings had a limited opportunity to immerse themselves into the human world of civilization, and this civilization has been predominantly and pervasively biocentric. Since the Industrial Revolution, however, after which both agriculturalism and pastoralism became economically marginal, and the adoption of technology greatly increased, the ability to separate oneself from biocentric institutions has increased proportionately, but the individual has remained himself a biological being, tied to the biological world through existential needs for personal sustenance. Thus our being biological has repeatedly brought us back to our biological origins. If civilization were to fail, we could still return to an almost exclusively biocentric context and — at least for those who survived this traumatic transition — life would go on.

The emergence of a technological milieu following the industrial revolution suggests the possibility of a technocentric civilization that is the successor to biocentric civilization. Indeed, we may even understand the emergence of a fully technocentric civilization as the telos of industrialized civilization. We can formulate this in greater generality, as this process may hold for any civilization whatsoever that originates as a civilization of planetary endemism and makes the transition to a technological civilization.

Should the intelligent (biological) agents that build a civilization cease to be biological and become, for example, technological instead of biological, over time those intelligent agents could grow apart from their biocentric origins, and the social institutions in which these intelligent agents participate will become increasingly less biocentric. Biocentricity, then, is a function of biological origins, i.e., biocentrism is a consequence of being biological (as I put it in The Biocentric Thesis), and biophilia is an expression of biocentricity. As a technological civilization grows away from its biocentric origins, it is likely to become less biophiliac over time, which will in turn allow for greater expression of technophilia.

An explicit formulation of the technocentric thesis

Let us try to give these ideas a more explicit formulation:

The Technocentric Thesis

Any fully technocentric civilization has evolved from a previous biocentric civilization by descent with modification.

…which implies its corollary formulated in the negative…

Technocentric Corollary

No civilization originates as a technocentric civilization.

By a “biocentric civilization” I mean a civilization that exemplifies the biocentric thesis. I have formulated a strong biocentric thesis (all civilizations in our universe begin as biocentric civilizations originating on planetary surfaces) and a weak biocentric thesis (all civilizations during the Stelliferous Era begin as biocentric civilizations originating on planetary surfaces), each of which has a corollary formulated in the negative. The technocentric thesis could also be given strong and weak formulations, e.g., all technocentric civilizations in our universe evolve from biocentric civilizations (strong) and all technocentric civilizations during the Stelliferous Era evolve from biocentric civilizations (weak). The weaker formulation is in each case constrained by temporal parameter while the stronger formulation is unconstrained.

The mechanism by which a technocentric civilization evolves from a biocentric civilization I call replacement, and replacement can be formulated as the replacement thesis:

The Replacement Thesis

All technocentric civilizations begin as biocentric civilizations and are transformed into technocentric civilizations through the replacement of biological constituents with technological constituents.

This in turn implies a negative formulation as its corollary:

Replacement Thesis Corollary

No technocentric civilization originates as a technocentric civilization, but emerges by replacement from a biocentric civilization of planetary endemism.

How far can replacement go? We can already see in our own industrialized civilization partial replacement, but can there be a complete replacement of biological constituents by technological constituents? For any civilizations originating in intelligent biological organisms, it is unlikely that living organisms could ever be completely eliminated, but they may be rendered superfluous for all practical purposes (i.e., superfluous to civilization).

The argument from consciousness

It would be possible to construct a scenario in which biology can never be completely eliminated as a constituent of civilization. Consider the following scenario, which I will call the argument from consciousness, based on the indispensability of consciousness to civilization and the unknown parameters of machine consciousness.

The Argument from Consciousness

I will assume that there is such a thing as consciousness, that human beings are conscious at least some of the time, and that this human consciousness plays a significant role in human existence and in the civilizations built by human beings. (It is necessary to make these rudimentary stipulations because it is not unusual to find consciousness dismissed, or called an “illusion,” or to see its role in the world minimized or marginalized.)

The view is prevalent, perhaps even dominant, in AI circles such that anything that can pass the Turing test must be called conscious. There is a degree of mutual reinforcement between this common view among AI researchers and the tacit positivism that continues to influence the development of contemporary science, which consigns consciousness of the sphere of metaphysics and thus rules out in principle any metaphysical entity that is consciousness. I will not here attempt to make a case for consciousness as a metaphysical entity, but I will assume, for the purposes of what follows, that a principled refusal to consider consciousness is a barrier to understanding human behavior, including the behavior of building civilizations.

Since we do not yet know what consciousness is, and we cannot produce a scientific account of consciousness, we do not know what the conditions of consciousness are. If we had a scientific theory of consciousness that allowed us to quantify consciousness by taking meaningful measures of consciousness, any putative consciousness, whether generated by a mechanism or by biology, natural or modified or fully synthetic, could be tested by such measures of consciousness and objectively determined to be conscious or not. We do not as yet possess any such science, nor can we take any such measurements.

Human and animal consciousness constitute existence proofs of the possibility of consciousness arising by natural means, and thus consciousness ought to be amenable to study by methodological naturalism, and also to replication. It is possible that consciousness can only be produced by biological means, i.e., it is possible that machine consciousness cannot be generated. The existence proof of consciousness provided by biological beings is not an existence proof of machine consciousness. Now, I personally think that machine consciousness will eventually come about, but we will not know that this is possible until it has been achieved.

Even if machine consciousness is impossible, it would still be possible to engineer consciousness by biological means, employing some variation on existing biological substrates of consciousness, or producing consciousness by way of synthetic or artificial biology. In this case, a civilization (or post-civilizational social institution) that preserves consciousness, or desires to preserve consciousness, will not be able to become purely technocentric in the sense of entirely eliminating biology, though the biology that is retained may be entirely subordinated to technical means and technical institutions. A civilization that retained consciousness through such biological means, but entirely within a technocentric context, could be called a technocentric civilization in which biology was ineradicable.

The argument from consciousness is merely an argument (and not a proof of anything), because the same absence of a science of consciousness that would allow us to take objective measures of consciousness is the absence of a science that would make it possible to prove either that consciousness can inhere in different kind of substrates (biological or mechanical, for example), or that consciousness can only be generated through biological means. Until we have a science of consciousness, we can advance this line of argumentation only through existence proofs, i.e., proofs of concept.

Even then, even given building a conscious machine, without a science of consciousness we would have no way to rigorously and objectively compare and contrast human consciousness with machine consciousness. One way to resolve this dilemma is the Turing test, as noted above, but no one who has any degree of scientific curiosity could be satisfied with cutting the Gordian knot of consciousness rather than unraveling it.

Final thought

One of the virtues of explicitly formulating one’s ideas as theses (or as arguments), as in the above, is that one can then turn to the explicit criticism of these theses, especially to the task of unpacking the assumptions embedded in the theses. Another virtue of explicit formulations is that they can be explicitly falsified. The existence of a civilization not derived from biological complexity emergent on a planetary surface would falsify the biocentric thesis.

These explicit formulations, then, are not be taken as definitive formulations. I do not consider the biocentric thesis, the technocentric thesis, or the replacement thesis to be in any sense definitive, but rather to be a point of departure in an analysis of the nature of civilization taken in its broadest signification and extrapolated to a cosmological scale. Thus I hope to return to each of these theses in order to tease out their assumptions in order to analytically approach the intuitive conception of civilization with which I began.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Ecological Conception of Civilization

9 May 2016

Monday

Recently in The Biological Conception of Civilization I defined civilization as a tightly coupled cohort of coevolving species. In proposing this definition, I openly acknowledged its limitations. This biological conception of civilization defines a biocentric civilization, and if civilization continues in its technological development, it may eventually pass from being a biocentric civilization, dependent upon intelligent organic species originating on planetary surfaces, to being a technocentric civilization, no longer dependent in this sense.

Even given these limitations of the biological conception of civilization, we need not abandon a biological framework entirely to converge upon a yet more comprehensive conception of civilization, beyond the biocentric, but still roughly characterized by conditions that we have learned from our tenure on Earth. Being ourselves an intelligent organic species existing on the surface of a planet, biological modes of thought can be made especially effective for minds such as ours, and it is in our cognitive interest to cultivate a mode of thought for which we are specially adapted.

Let us, then, go a little beyond a strictly biological conception of civilization and formulate an ecological conception of civilization. To make this conception immediately explicit, here is a first formulation…

The Ecological Conception of Civilization:

Civilization is niche construction by an intelligent species.

This formulation of the ecological conception of civilization could be amended to read, “by an intelligent species or by several intelligent species,” in order to anticipate the possibility of intelligence-rich biospheres that give rise to civilizations constituted by multiple intelligent species.

What is niche construction? Here is a sketch of the idea from a book on niche construction:

“…organisms… interact with environments, take energy and resources from environments, make micro- and macrohabitat choices with respect to environments, construct artifacts, emit detritus and die in environments, and by doing all these things, modify at least some of the natural selection pressures present in their own, and in each other’s, local environments.”

Niche Construction: The Neglected Process in Evolution, F. John Odling-Smee, Kevin N. Laland, and Marcus W. Feldman, Monographs in Population Biology 37, Princeton University Press, 2003, p. 1

The authors go on to say:

“All living creatures, through their metabolism, their activities, and their choices, partly create and partly destroy their own niches, on scales ranging from the extremely local to the global.”

Ibid.

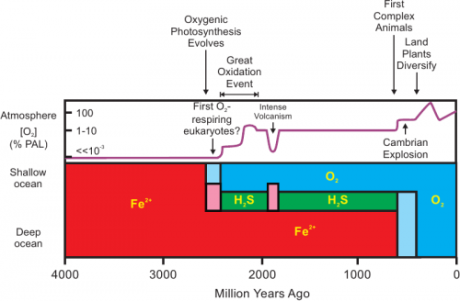

Human interaction with the terrestrial environment is an obvious example of taking energy and resources from the environment on a global scale, altering the selection pressures on our own evolution as a species by both creating and destroying a niche for ourselves. We are not the first terrestrial organisms to act upon the planet globally; when stromatolites (microbial mats composed of cyanobacteria) were the dominant life form on Earth, their photosynthetic processes ultimately produced the Great Oxygenation Event and catastrophically changed the biosphere. Had it not been for that global catastrophic change of the biosphere, oxygen-breathing organisms such as ourselves could not have evolved.

‘The Great Oxygenation Event (GOE), also called the Oxygen Catastrophe, Oxygen Crisis, Oxygen Holocaust, Oxygen Revolution, or Great Oxidation, was the biologically induced appearance of dioxygen in Earth’s atmosphere.’ from Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Oxygenation_Event)

Though we are not the first terrestrial organism to shape the biosphere entire, we are the first intelligent terrestrial agents to shape the biosphere, and it has been the application of human intelligence to the problem of human survival that has resulted in human beings adapting their activity to every terrestrial biome and so eventually constructing civilization. At the stage of the initial emergence of civilization, the biological and ecological conceptions of civilizations coincide, as niche construction takes the form of engineering a coevolving cohort of species beneficial to the intelligent agent intervening in the biosphere. In later stages in the development of civilization, the ecological conception is shown to be more comprehensive than the biological conception of civilization, and subsumes the biological conception of civilization.

Not any cohort of coevolving species constitutes a civilization. Pollinating insects (bees) and flowers are involved in what might be called a tightly-coupled cohort of coevolving species, but we could not call bees and flowers together a civilization. Perhaps on other worlds the distinction between what we call civilization and coevolution in the natural world would not be so evident, and we could not as confidently make the distinction. For us, however, this distinction seems obvious. Why? At least one difference between civilization and naturally occurring coevolution is that the tightly-coupled cohort of coevolving species that we call civilization has been purposefully engineered for the benefit of the intelligent species that has demonstrated its agency through this engineering of a niche for itself. Moreover, the engineered niche is entirely dependent upon ongoing intervention to maintain this engineered niche. In the absence of civilization, the tightly-coupled cohort(s) of coveolving species would unravel, while naturally occurring instances of coevolution would continue unchanged, i.e., they would continue to coevolve. (I leave it as an exercise to the reader to compare this observation to Schrödinger’s definition of life in thermodynamic terms.)

The necessary role of an intelligent agent in maintaining a coevolutionary cohort of species points beyond the biological conception of civilization to the ecological conception of civilization, which in term points beyond civilizations constructed by biological agents to the possibility of niches constructed by any intelligent agent whatsoever. This makes the ecological conception of civilization more comprehensive than the biological conception of civilization, as the intelligent agents involved in niche construction need not be biological beings. However, biological beings are likely to be the intelligent agents with which civilization begins.

In the kind of universe we inhabit, during the Stelliferous Era biology represents the first possible emergence of intelligent agency, hence the first possibility of intelligent niche construction. (I could hedge a bit on this and instead assert that biological agents are the first likely emergence of intelligent agents, as Abraham Loeb has posited the possibility of life in the very early universe — cf. “The Habitable Epoch of the Early Universe” — but I consider this scenario to be unlikely, and the possibility of such life yielding civilization even less likely.) This biocentric possibility of intelligent niche construction can later be supplemented or replaced by later forms of emergent complexity consistent with intelligent agency and capable of niche construction (which latter could involve either building on existing forms of intelligent niche construction or innovating new forms of intelligent niche construction transcending what we today understand as civilization).

The biological conception of civilization — an engineered coevolving cohort of species — constitutes one possible form of niche construction. That is to say, in managing an ecosystem so that it produces a disproportionate number of the plants and animals consumed as food or other products for the use of the directing intelligent agent (human beings in our case), human beings have attained the first possible stage of intelligent niche construction, which is essentially a delineation of biocentric civilization, but the ecological conception of civilization can be adapted to the understanding of non-biocentric civilizations, as, for example, in the case the technocentric civilizations. The various kinds of civilization that we have seen on Earth — including but not limited to agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization and industrial-technological civilization — represent distinct forms of intelligent niche construction, and therefore all fall within the ecological conception of civilization. Civilizations constructed by post-biological agents in the form of technological beings may build upon these constructed niches or construct niches more distinctly adapted to post-biological agents (which may be technological agents).

The ecological conception of civilization lends itself to technocentric extrapolation in so far as the ecological recognition of the biology of planetary endemism being dependent on solar flux is readily adapted to conceptions of civilization that have emerged from the work of Dyson and Kardashev. Dyson famously imagined stars so surrounded by the productions of a technological civilization that only the waste heat of these civilizations would be visible to us in the infrared spectrum, and Kardashev equally famously translated this idea into a formalism representing civilization types in terms of total energy resources commanded by a civilization. Even these distant extrapolations of the possibility of our technological civilization are still recognizably dependent upon stellar flux, no less than the biomass of our terrestrial environment is dependent upon solar flux, as stellar flux represents the primary source of readily available energy during the Stelliferous Era. In this way, even technocentric civilizations constructed by post-biological intelligent agents are continuous with the civilizations of planetary endemism emerging from the biology of planetary surfaces, and both are describable in ecological terms.

It could be said that the ecological conception of civilization presupposes the biological conception, because ecological systems supervene on biological systems (or, at least, ecological systems have supervened upon biological systems to date, but this is not a necessary relationship and may be superseded in the fullness of time), and an ecological perspective provides a conceptual framework placing civilization in the context of the natural world from which it emerged and upon which it depends, as well as placing any given civilization in the context of other civilizations. This latter function — providing a systematic framework for the interaction of civilizations — ultimately may be the most valuable aspect of the ecological conception of civilization, but one that can only be suggested at present. The ecological relationships familiar to us from the study of living organisms — mutualism (or symbiosis), commensalism, predation, and parasitism — may hold for civilizations also, but this kind of parallelism cannot be assumed. The ecological relationships among civilizations — i.e., among intelligent species that have engaged in niche construction — may well be more complex than the ecological relationships among organisms, but this is a matter for further study that I will not attempt to elaborate at present.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

The Biological Conception of Civilization

26 March 2016

Saturday

It was until recently uncontroversial that civilization begins with settled agriculturalism. The excavations at Göbekli Tepe have shown an unexpected light on some of the earliest human communities. The structures at Göbekli Tepe seem to have been been ritual spaces — perhaps the world’s earliest example of monumental architecture, one of the sure markers of civilization — but evidence suggests that the peoples who gathered at Göbekli Tepe neither cultivated grains nor actively engaged in pastoralism. If Göbekli Tepe provides an alternative to the agricultural model of what civilization might have been, it was not a model that was widely adopted; indeed, the site seems to have been not only abandoned, but purposefully covered over, and does not seem to have served as a social model for any other society except for the other hills in the immediate area that probably contain similar remains. An obvious alternative hypothesis is that Göbekli Tepe represents a transitional stage on the way to the development of settled agricultural civilization.

Göbekli Tepe, where large-scale social organization may have preceded both agriculturalism and pastoralism.

Thus while settled agriculturalism might not be the earliest or only model for the origins of civilization, it is unquestionably the most pervasive and the most successful. Independently in widely separated geographical regions peoples settled in communities and engaged in the production of staple crops. From these communities cities grew, and a network of such cities has meant civilization. Just as there were likely alternative paths to civilization that were abandoned in favor of the most robust path, so there have been alternative forms of the development of civilization. Several thousand years after the breakthrough to settled agriculturalism as a form of large-scale social organization, an alternative form emerged in Central Asia: pastoralism, in which the large-scale domestication and herding of animals substituted for the large-scale domestication of staple crops. This is not commonly recognized as a distinct form of civilization, because nomadic herders have rarely developed written languages, whereas settled agriculturalists did invent written languages, wrote histories, and called the nomadic pastoralists “barbarians” — a cultural slander that has endured to the present day.

Nomadic pastoralism: “The Qashqai of Iran use a system of opportunistic management that has evolved over centuries of dependence on a varied and unpredictable environment.” (from http://www.fao.org/nr/giahs/candidate-system/candidate/qashqai/en/)

Common to both settled agriculturalism and nomadic pastoralism as large-scale forms of social organization is the coupling of the fate of other species with human beings. Domestication, whether of plants or animals, lies at the basis of civilization as we know it. This suggests what I call the biological conception of civilization. I first explicitly formulated the biological conception of civilization in my Centauri Dreams post Transhumanism and Adaptive Radiation:

“Each biome into which human beings inserted themselves during our planetary diaspora out of our African origins has made available a unique cohort of species, some of which have been domesticated and the fates of which have thus become tied to human beings and their civilization (no less than our fate is joined to theirs). Terrestrial food production involves this tightly-coupled cohort of co-evolving species dependent upon one another as a consequence of domestication (which latter formulation would constitute a biologically minimalist conception of civilization). This species cohort varies according to endemic species, topography, and climatic conditions… Thus each region of Earth not only possesses a cultural diversity of civilizations, but also a biological diversity of civilizations, each of which may be defined in terms of the unique cohort of tightly-coupled co-evolving species. To date, this process has been an exclusively terrestrial one, but when cohorts of species representative of terrestrial civilizations leave Earth and establish themselves in other environments, the same principles will be iterated at higher orders of magnitude.”

Occasionally I refer to civilizations as “biocentric” (as, for example, in From Biocentric Civilization to Post-biological Post-Civilization). Biocentric civilization can defined in terms of the biological conception of civilization: a biocentric civilization is a civilization that can be exhaustively described by the biological conception of civilization. As a civilization begins to transcend its biocentric origins, the biological conception of civilization becomes less adequate for the description of that civilization. If a civilization were ever to wholly transcend its biocentric origins, the biological conception of civilization would be wholly inadequate and would at that point fail to capture the meaning of civilization. Yet as long as civilization continues to be associated with the biological beings from which it originated, it will continue to have recognizably biocentric features.

One consequence of the biocentric origins of civilization as we know it (which I recently formulated in Another Way to Think about Civilization), is that the human control of the reproduction of plants and animals has led to a radical change in the biology of our homeworld. One way to understand this radical change in the terrestrial biosphere due to civilization would be to identify the advent of civilization with initiating the process of creating an artificial biosphere in which naturally occurring ecosystems are progressively supplanted by artificial ecosystems constructed for the purpose of meeting the needs of civilization.

The interpolation of artificially maintained ecosystems within a wild ecosystem would simply disappear if it were not sustained by the agents who originated it. But as the artificial ecosystem of civilization expands and supplants the wild ecosystem of the planet, its expansion becomes a selection event that selects for domesticated species (as well as a range of parasitical species) and selects against non-domesticated species. As civilization has expanded, wild ecosystems have been pushed to the margins of the civilized world and the greater part of the planet has become dominated by human activities that have shaped the biosphere in a distinctive way. Non-agricultural peoples have also been pushed to the margins. When artificial ecosystems were first introduced by human beings, almost all of the world was the province of nomadic hunter-gathers who wandered freely through a wild landscape. Now the entire surface of our homeworld has been meticulously divided up among nation-states that all have their origins in the states or empires of agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization.

On Earth, the artificial biosphere created and maintained by biocentric civilization supplants a wild biosphere, but biocentric civilization could continue its development, facilitated by the resources of emergent technocentric civilization, through the extension of civilization’s artificial biospheres to other worlds or to artificial habitats. If the artificial biosphere of civilization is transitioned into artificial habitats, artificial ecosystems can be expanded without limit under controlled conditions that will allow for an even greater precision in the management artificial ecosystems. In so far as the initial creation of artificial ecosystems has aimed at greater human control over agricultural outcomes, we can regard this as the telos of agriculture, evident since the earliest stirrings of civilization, and the only context in which the implications of artificial ecosystems can be fully explored. Thus the departures from a strictly biological conception of civilization that point to a nascent technocentric civilization becomes another form of exaptation of coevolution, in which technology coevolves with biology by providing new scope to biocentric civilization.

The biological conception of civilization outlined above is neither anthropocentric nor necessarily tied to terrestrial forms of life, although we must express the concept by means of life as we know it; the biological conception of civilization is generalizable to any biota. Any biosphere that is sufficiently complex for the emergence of intelligent life will embody a high degree of biodiversity, i.e., a large number of distinct species forming complex biological communities, and we can furthermore expect that species will be grouped in the biomes to which they are endemic. Thus the same conditions as are found on Earth, and which have been exapted by human intelligence to produce civilization in the form of a cohort of coevolving species, will likely be present on any world with an intelligent species, and equally available for exaptation in the civilizing process.

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

Civilizations of Planetary Endemism: Part IV

18 February 2016

Thursday

“Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system. At 2,263 miles in diameter, it is slightly larger than Earth’s moon.” (NASA)

In earlier posts of this series on Civilizations of Planetary Endemism we saw that planets not only constitute a “Goldilocks” zone for liquid water, but also for energy flows consistent with life as we know it. I would like to go into this in a little more detail, as there is much to be said on this. It is entirely possible that energy flows on a planet or moon outside the circumstellar habitable zone (CHZ) could produce sufficient heat to allow for the presence of liquid water in the outer reaches of a planetary system. Indeed, it may be misleading to think of habitable zones (for life as we know it) primarily in terms of the availability of liquid water; it might be preferable to conceive a habitable zone primarily in terms of regions of optimal energy flow (i.e., optimal for life as we know it), and to understand the availability of liquid water as a consequence of optimal energy flow.

Our conception of habitability, despite what we already know, and what we can derive from plausible projections of scientific knowledge, is being boxed in by the common conceptions (and misconceptions) of biospheres and CHZs. We can posit the possibility of “oasis” civilizations on worlds where only a limited portion of the surface is inhabitable and no “biosphere” develops, although enough of a fragment of a biosphere develops in order for complex life, intelligence, and civilization to emerge. We do not yet have an accurate term for the living envelope that can emerge on a planetary surface, but which does not necessary cover the entire planetary surface. I have experimented with a variety of terms to describe this previously. For example, I used “biospace” in my 2011 presentation “The Moral Imperative of Human Spaceflight,” but this is still dissatisfying.

As is so often the case, we run into problems when we attempt to extrapolate Earth sciences formulated for the explicit purpose of accounting for contingent terrestrial facts, and never conceived as a purely general scientific exercise applicable to any comparable phenomena anywhere in the universe. This is especially true of ecology, and since I find myself employing ecological concepts so frequently, I often feel the want of such formulations. Ecology as a science is theoretically weak (it is much stronger on its observational side, which goes back to traditional nature studies that predate ecology), and its chaos of criss-crossing classification systems reflects this.

There are a great many terms for subdivisions of the biosphere — ecozone, bioregion, ecoregion, life zone, biome, ecotope — which are sometimes organized serially from more comprehensive to less comprehensive. None of these subdivisions of a biosphere, however, would accurately describe the inhabited portion of a world on which biology does not culminate in a biosphere. Perhaps we will require recourse to the language and concepts of topology, since a biosphere, as a sphere, is simply connected. The bioring of a tidally locked M dwarf planet would not be simply connected in this topological sense.

If we conceptualize habitable zones not in terms of a celestial body being the right temperature to have liquid water on its surface, or perhaps in a subsurface ocean, but rather view this availability of liquid water as a consequence of habitable zones defined in terms of the presence of energy flows consistent with life as we know it, then we will need to investigate alternative sources of energy flow, i.e., distinct from the patterns of energy flow that we understand from our homeworld. Energy flows consistent with life as we know it are consistent with conditions that allow for the presence of liquid water on a celestial body, but this also means energy flows that would not overwhelm biochemistry and energy flows that are not insufficient for biochemistry and the origins and maintenance of metabolism.

Energy flows might be derived from stellar output (thus a consequence of gravitational confinement fusion), from radioactivity, which could take the form of radioactive decay or even a naturally-occurring nuclear reactor, as as Oklo in Gabon (thus a consequence of fission), from gravitational tidal forces, or from the kinetic energy of impacts. All of these sources of energy flows have been considered in another connection: suggested ways to resolve the faint young sun paradox (the problem that the sun was significantly dimmer earlier in its life cycle, while there still seems to have been liquid water on Earth) are the contributions of other energy sources to maintaining a temperature on Earth similar to that of today, including greater tidal heating from a closer moon, more heating from radioactive decay, and naturally occurring nuclear fission.

It would be possible in a series of thought experiments to consider counterfactual worlds in which each of these sources of energy flow are the primary source of energy for a biosphere (or a subspherical biological region of a planetary surface). The Jovian moon Io, for example, is the most volcanically active body in our solar system; while Io seems to barren, one could imagine an Io of more clement conditions for biology in which the tidal heating of a moon with an atmosphere was the basis of the energy flow for an ecosystem. A world with more fissionables in its crust than Earth (the kind of worlds likely to be found during the late Stelliferous Era under conditions of high metallicity) might be heated by radioactive decay or natural fission reactors (or some combination of the two) sufficient to generate energy flows for a biosphere, even at a great distance from its parent star. It seems unlikely that kinetic impacts from collisions could provide a sufficiently consistent flow of energy without a biosphere suffering mass extinctions from the same impacts, but this could merely be a failure of imagination. Perhaps a steady rain of smaller impacts without major impacts could contribute to energy flows without passing over the threshold of triggering an extinction event.

Each of these exotic counterfactual biospheres suggests the possibility of a living world very different from our own. The source of an energy flow might be inconsistent, that is to say, consistent up to the point of making life possible, but not sufficiently consistent for civilization, or the development of civilization. That is to say, it is possible that a planetary biosphere or subspheric biological region might possess sufficient energy flows for the emergence of life, but insufficient energy flows (or excessive energy flows) for the emergence of complex life or civilization. Once can easily imagine this being the case with extremophile life. And it is possible that a bioregion might possess sufficient energy flows for the emergence of a rudimentary civilization, but insufficient for the development of industrial-technological civilization that can make the transition to spacefaring civilization and thus ensure its longevity.

Civlizations of planetary endemism on these exotic worlds would be radically different from our own civilization due to differences in the structure and distribution of energy flow. Civilizations of planetary endemism are continuous with the biosphere upon which they supervene, so that a distinct biosphere supervening upon a distinct energy flow would produce a distinct civilization. Ultimately and ideally, these distinct forms of energy flow could be given an exhaustive taxonomy, which would, at the same time, be a taxonomy of civilizations supervening upon these energy flows.

However, the supervenience of civilization upon biosheres and biospheres upon energy flows is not exhaustive. Civilizations consciously harness energy flows to the benefit of the intelligent agent engaged in the civilizing process. The first stage of terrestrial civilization, that of agricuturalism and pastoralism, was a natural extension of energy flows already present in the bioshere, but once the breakthrough to industrialization occurred, energy sources became more distant from terrestrial energy flows. Fossil fuels are, in a sense, stored solar energy, and derive from the past biology of our planet, but this is the use of biological resources at one or more remove. As technologies became more sophisticated, in became possible to harness energy sources of a more elemental nature that were not contingent upon extant energy flows on a planet.

It may be, then, that biocentric civilizations are rightly said to supervene upon biospheres. However, with the breakthrough to industrialization, and the beginning of the transition to a technocentric civilization, this supervenience begins to fail and a discontinuity is interpolated between a civilization and its homeworld. According to this account, the transition from biocentric to technocentric civilization is the end point of civilizations of planetary endemism, and the emergence of a spacefaring civilization as the consequence of technologies enabled by technocentric civilization is a mere contingent epiphenomenon of a deeper civilizational process. This in itself provides a deeper and more fundamental perspective on civilization.

. . . . .

Planetary Endemism

● Civilizations of Planetary Endemism: Introduction (forthcoming)

● Civilizations of Planetary Endemism: Part I

● Civilizations of Planetary Endemism: Part II

● Civilizations of Planetary Endemism: Part III

● Civilizations of Planetary Endemism: Part IV

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . .

From Biopower to Technopower

3 April 2014

Thursday

Among the many theoretical innovations for which Michel Foucault is remembered is the idea of biopower. We can think of biopower as a reformulation of perennial Foucauldian themes of the exercise of power through institutions that do not explicitly present themselves as being about power. That is to say, the subjugation of populations is brought about not through the traditional institutions of state power, but by way of new institutions purposefully constituted for the reason of monitoring and administrating the unruly bodies of the individuals who collectively constitute the body politic.

Foucault introduced the idea of biopower in The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, in the chapter, “Right of Death and Power over Life.” Like his predecessor in France, Descartes, Foucault writes in long sentences and long paragraphs, so that it is difficult to quote him accurately without quoting him at great length. His original exposition of biopower needs to be read in full in its context to appreciate it, but I will try to pick out a few manageable quotes to give a sense of Foucault’s exposition.

Here is something like a definition of biopower from Foucault:

“…a power that exerts a positive influence on life, that endeavors to administer, optimize, and multiply it, subjecting it to precise controls and comprehensive regulations.”

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, translated from the French by Robert Hurley, New York: Pantheon, 1978, p. 137

Later Foucault names specific institutions and practices implicated in the emergence of biopower:

“During the classical period, there was a rapid development of various disciplines — universities, secondary schools, barracks, workshops; there was also the emergence, in the field of political practices and economic observation, of the problems of birthrate, longevity, public health, housing, and migration. Hence there was an explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugation of bodies and the control of populations, marking the beginning of an era of ‘biopower’.”

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, translated from the French by Robert Hurley, New York: Pantheon, 1978, p. 140

Prior to the above quotes, Foucault begins his exposition of biopower with an examination of the transition from the traditional “power of life and death” held by sovereigns, which Foucault says was in fact restricted to the power of death, i.e., the right of a sovereign to deprive subjects of their life, to a fundamental change in emphasis so that the “power of life and death” became the power of life, i.e., biopower. The shift from right of death to power over life is what marks the emergence of biopower. Foucault, however, explicitly acknowledged that,

“…wars were never as bloody as they have been since the nineteenth century, and all things being equal, never before did regimes visit such holocausts on their own populations.”

Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, translated from the French by Robert Hurley, New York: Pantheon, 1978, pp. 136-137

This thanatogenous phenomenon is what Edith Wyschogrod called “The Death Event” (which I wrote about in Existential Risk and the Death Event), but if Foucault is right, it is not the Death Event that defines the social milieu of industrial-technological civilization, but rather a “Life Event” that we must postulate parallel to the Death Event.

What is the Life Event parallel to the Death Event? This is nothing other than the loss of belief in an otherworldly reward after death (which defined social institutions from the Axial Age to the Death of God, and which may be the source of the relation between agriculture and the macabre), and the response to this lost possibility of eternal bliss by the quest for health and felicity in this world and in this life.

A key idea in Foucault’s exposition of biopower hinges upon how the contemporary power over life that has replaced the arbitrary right of death on the part of the sovereign has been seamlessly integrated into state institutions, so that state institutions are the mechanism by which biopower is applied, enforced, expanded, and preserved over time. From this perspective, biopower becomes the unifying theme of Foucault’s series of earlier books on asylums for the insane, prisons for the criminal, and clinics for the diseased, all of which institutions had the character of the, “subjugation of bodies and the control of populations” through “precise controls and comprehensive regulations.” (At this point Foucault could have profited from the work of Erving Goffman, who identified a particular subset of “total institutions” that completely regulated the life of the individual.)

What we are seeing today is that the “success” of the imperative of biopower has resulted in longer and healthier lives among docile populations, who dutifully report to their mind-numbing labor of choice and rarely riot. To step outside the confines of acceptable social behavior is to find oneself committed to a total institution such as an asylum or a prison, so that that individual self-censors and self-restrains in order to preempt state action that would bring his behavior into conformity with the norm. With the imperative of biopower largely established and largely uncontested, the next frontier is the imperative of extending biopower to the mind, and rendering the population intellectually docile in the way that bodies have been regulated and rendered docile.

The extension of biopower to the life of the mind might be called psychopower. This extension presumably involves parallel regimes of psychic hygiene that will give the individual mind a longer, healthier life, as biopower has bequeathed a longer, heathier life to the body, but the healthy and hygienic mind is also a mind that has subjugated to precise controls and comprehensive regulation. Cognitive pathology here becomes a pretext for state intervention into the private consciousness of the individual.

The proliferating regimes of therapy, counseling, psychiatric services, so-called “social” services that today almost invariably have a psychiatric component, not to mention the bewildering range of psychotropic medications available to the public — and apparently prescribed as widely as they are known and available — are formulated with an eye to regimenting the intellectual life of the body politic. And this “eye” is none other than the medical gaze now trained upon the individual’s introspection.

The mechanism by which psychopower is obtained has, to date, been the same state institutions that have overseen biopower, but this is already changing. The emergence of biopower in the period of European history that Foucault called “The Classical Age” (“l’âge classique”) was a product of agricultural civilization (specifically, agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization) at its most mature and sophisticated stage of development, shortly before all that agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization had built in terms of social institutions would be swept away by the unprecedented social change resulting from the industrial revolution, which would eventually begin to converge upon a new civilizational paradigm, that of industrial-technological civilization.

Thus biopower at its inception was the ultimate regulation of a biocentric civilization. As civilization makes a transition from being biocentric to technocentric, new instrumentalities of power will be required to implement a regime of docility under radically changed socioeconomic conditions, i.e., technocentric socioeconomic conditions, and this will require technopower, which will take up where biopower leaves off. Biopower conceived after the manner of biocentric civilization, of which agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization is an expression, cannot answer to the regulatory needs of a technocentric civilization, which thus will require a regime of technopower.

Already this process has begun, though the transition from biocentric civilization is likely to be as slow and as gradual as the transition from hunter-gatherer nomadism to the discipline of settled civilization, in which the institutions of biopower first begin to assume their inchoate forms. What we are beginning to see is the transition from state power being embodied in and exercised through social institutions to state power being embodied in and exercised through technological infrastructure. Central to this development is the emergence of the universal surveillance state, in which the structures of power are identical to the structures of electronic surveillance.

The individual participates in social media for the presumptive opportunities for self-expression and self-development, which are believed to have many of the positive social effects that the regulation of docile bodies has had upon longevity and physical comfort. The structure of these networks, however, serves only to reinforce the distribution of power within society. The more alternatives we have for media, the more we hear only of celebrities (in what is coming to be called a “winner take all” economic model). At the same time that the masses are encouraged to occlude their identity through the iteration of celebrity culture that renders the individual invisible and powerless, the individual self is relentlessly marginalized. In Is the decontextualized photograph the privileged semiotic marker of our time? I argued that the proliferating “selfies” that populate social media, as a self-objectification of the self, are nothing but the “death of the self” prognosticated by post-modernists.